Abstract

Introduction: In this study, the aim was to evaluate the effect of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) on quality of life in postmastectomy lymphedema (PML) patients.

Methods: Twenty-four female patients diagnosed with PML were included in the study. Demographic features, disease and lymphedema duration, cancer type, cancer stage, operation type, radiotherapy and chemotherapy history, lymphedematous and dominant extremity, and body mass index (BMI) were recorded. LLLT was applied to the affected limb as 904 nm, 1.5 Joule/cm2, three days a week for a total of 8 weeks. Quality of life assessment, lymphedema severity, and lymphedema staging was performed to measure effectiveness before and after treatment. Patients with lymphedema not associated with breast cancer and/or primary lymphedema, ongoing radiotherapy, metastatic high-grade breast cancer, acute infection, and deep vein thrombosis were excluded from the study.

Results: Modified radical mastectomy was reported in 18 patients; total mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy were reported in 6 patients. Of the patients, 45.8% were stage 3, and 54.2% were stage 2. Of the patients, 95.8% had a history of chemotherapy and 83% of radiotherapy after surgery. In this study, following LLLT, improvement of lymphedema stage and severity were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). In the evaluation of lymphedema quality of life, there was a statistically significant improvement in parameters including function, appearance, clinical symptoms, and overall quality of life (p < 0.05). However, no improvement was observed in the emotional state parameter (p > 0.05).

Conclusion: Thus, LLLT is a safe treatment method that increases the quality of life in breast cancerrelated lymphedema patients.

Introduction

Today, breast cancer is the most important cause of cancer-related mortality among women1. As the incidence of the disease increases, the number of women affected by complications also increases. Although treatments like surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy reduce breast cancer mortality rates, each can also cause different side effects. Postmastectomy lymphedema (PML) is one of the most severe complications in terms of treatment, appearing immediately after the surgery, or in most cases, in the first two years after breast cancer treatment2, 3. Conservative treatment modalities that include manual lymphatic drainage, pneumatic compressive pumps, low-level laser, compression bandages, and compression garments are recommended for the treatment of PML4, 5. However, it is also essential to do regular exercises to increase weight control and scapulothoracic, elbow, and wrist mobility6.

Laser treatment has biostimulatory, anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. The wavelength range of 650-1000 nm is used in low-level laser therapy (LLLT). Laser therapy increases the pumping speed and regeneration (lymphangiogenesis) of lymphatic vessels and the lymphatic flow by reducing pain, softening fibrous tissue, and minimizing surgical scarring. Positive effects were reported in the treatment of surgical scars and lymphedematous extremities associated with lymphedema developing after mastectomy7, 8. In this study, the purpose was to show the effect of LLLT on clinical symptoms, functional status, and quality of life in patients with lymphedema that develops after breast cancer-related surgery.

Materials — Methods

A total of 24 female patients who applied to SANKO University, Faculty of Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinic (Turkey) for the first time or for follow-up purposes, between March 2019 and January 2020, and who were diagnosed with PML were included in the present study. An information form was created to record the sociodemographic characteristics and findings of the examination of the patients who participated in this prospective study. The ages, education levels, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), disease and lymphedema durations, cancer stages, operation types, history of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as well as lymphedema-affected and dominant limb and shoulder range of the patients were recorded. The patients were informed about the study before filling out the questionnaire, and informed consent forms were obtained. Lymphedema and/or primary lymphedema patients who were not associated with breast cancer, patients with advanced-stage breast cancer with metastasis and ongoing radiotherapy, patients with thrombosis, and those with active infection were not included in the study.

In lymphedema evaluation, circumferential measurements (cm) were taken from the affected limb with a tape measure, which is an easy-to-use, hygienic and inexpensive method. The measurements were taken from 10 cm distal and proximal level of bilateral metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists and elbow antecubital fossa. The lymphedema severity was determined by the differences between the extremities which were adopted by the American Physiotherapy Association (less than 3 cm, mild; between 3 and 5, moderate; above 5, severe lymphedema)9. The Lymphedema Quality of Life Survey (LYMQOL-Arm) that had Turkish validity and reliability was applied to the patients to measure the effectiveness of the treatment10. In the questionnaire that consisted of 28 questions, the questions were collected under four areas as function, appearance, clinical symptoms, and psychological state. Each subparameter score has a range between one and four; high scores show a poor quality of life. The last parameter, which evaluates the overall quality of life as a whole, is rated between 0 and 10. Higher scores show a better overall quality of life. Patients' clinical lymphedema staging was evaluated by the grading based on the International Society of Lymphology, with a degree between zero and four. In this respect, patients were classified as: Stage 0-Subclinical lymphedema (weight sensation and edema that is not sensitive to the eye), Stage 1 — Spontaneous reversible (increase in upper extremity diameter, weight sensation and pitting edema), Stage 2 — Spontaneous irreversible (non-pitting edema, skin has trophic changes, fibrosis), and Stage 3 — Lymphostatic elephantiasis (advanced lymphedema and changes in the skin)11.

A gallium arsenide (Ga-As) diode laser system was used to transmit laser energy to each point (0.5 cm2) at 1.5 Joule/cm2. The laser output power was 10 W at 904 nm wavelength in pulsed mode (frequency 3000 Hz, pulse width 130 ns, emission power 4 mJ/s). Patients received the treatment protocol three times a week for eight weeks. In each session, 10 points in the axillary and antecubital region were irradiated using a laser device with a particular head in contactless mode at a distance of 1 cm from the skin surface. All patients wore protective glasses. The questionnaires were performed before and one week after the end of the treatment.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 23 Program was used to analyze the data of the patients. Mean values, standard deviation, median, lowest, highest, frequency, and ratios were used in the descriptive statistics. The data obtained before and after the laser treatment were compared using the Wilcoxon-Signed test, which is a comparison method of non-parametric dependent two groups; p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

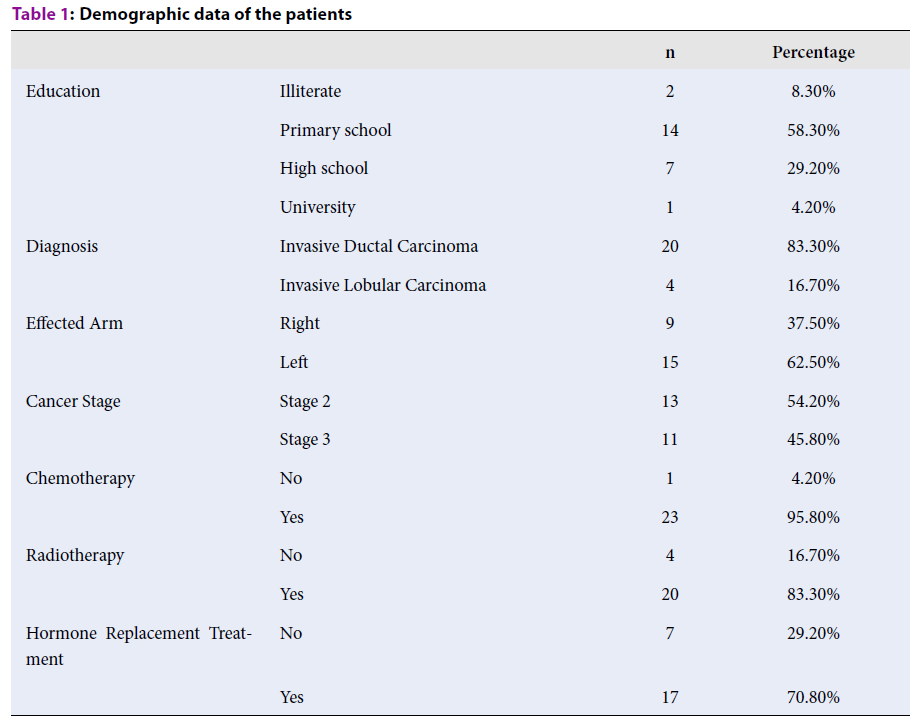

The mean age of the patients included in the study was 54.42 ± 9.32, and the mean BMI was 30.40 ± 5.35 kg/m². The mean disease duration was 30 months, and the lymphedema duration was 9 months. When the educational status of the participants was examined, it was determined that 8.3% received no education, 58.3% were primary school graduates, 29.2% were high school graduates, and 4.2% were university graduates. A total of 83.30% of the patients were followed up due to invasive ductal carcinoma and 16.70% due to invasive lobular carcinoma. When the cancer stages of the patients were evaluated, it was determined that 45.8% were Stage 3 and 54.2% were Stage 2 (Table 1). The patients did not have skin lesions like erythema, ulceration, or rash. Nine of the patients (37.5%) were affected in the upper-right extremity, and 15 (62.5%) were affected in the upper-left limb. The dominant limb of the majority of the participants (75%) was the right side. Eighteen of the patients had undergone modified radical mastectomy, and six had undergone total mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. In total, 95.8% of the patients had a history of chemotherapy, 83% had radiotherapy, 12.5% had neoadjuvant chemotherapy history, and 70.8% were still receiving hormone replacement therapy. All the patients completed their sessions at the end of the second month. In this study, the improvements in the extremity volume, lymphedema stage, and severity parameters in pre-and post-laser treatment were statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The most obvious improvement was decreased environmental measurement in the extremity. In the LYMQoL-Arm scoring, although there were statistically significant improvements in the subparameters of function, external appearance, clinical symptoms, and overall quality of life (p < 0.05), no statistically significant improvements were detected in the emotional state subscale (p > 0.05). The effects of laser treatment were not found to be statistically significant on the shoulder movements that had normal basal values (Table 2).

| n | Percentage | ||

| Education | Illiterate | 2 | 8.30% |

| Primary school | 14 | 58.30% | |

| High school | 7 | 29.20% | |

| University | 1 | 4.20% | |

| Diagnosis | Invasive Ductal Carcinoma | 20 | 83.30% |

| Invasive Lobular Carcinoma | 4 | 16.70% | |

| Effected Arm | Right | 9 | 37.50% |

| Left | 15 | 62.50% | |

| Cancer Stage | Stage 2 | 13 | 54.20% |

| Stage 3 | 11 | 45.80% | |

| Chemotherapy | No | 1 | 4.20% |

| Yes | 23 | 95.80% | |

| Radiotherapy | No | 4 | 16.70% |

| Yes | 20 | 83.30% | |

| Hormone Replacement Treatment | No | 7 | 29.20% |

| Yes | 17 | 70.80% |

| Lymphedema Evaluation | p |

| Extremity circumference | 0.000 |

| Lymphedema stage | 0.001 |

| Lymphedema severity | 0.000 |

| Function | 0.001 |

| External image | 0.001 |

| Clinical symptoms | 0.000 |

| Psychological condition | 0.091 |

| General quality of life | 0.011 |

Discussion

The PML-breast cancer relation is the most common complication after surgery or other treatments. There are edema, pain, and disability in the affected arm. PML has been reported to cause a low quality of life, social isolation, emotional, and cognitive problems12. The treatment of the lymphedema associated with breast cancer is complicated. Treatment approaches are aimed to reduce swelling in the extremity, to control symptoms, and reducing complications. The goal of all treatment modalities is to prevent lymphedema in high-risk patients and to improve their quality of life. In this study, it was observed that laser therapy improves the quality of life in PML patients.

Patients are given preventive measures and training on preventing the development or increase of lymphedema in the early period in the treatment of PML. It is aimed to develop new collateral drainage pathways to control the decongestion of the existing lymphatic pathways and long-term swelling to reduce the volume of extremities13. All studies conducted on lymphedema emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Skincare, static compression bandages and garments, elevation, exercise, and weight control are recommended in the BMJ-Best Lymph Practice Guide. In this guide, manual lymph drainage, intermittent pneumatic compression, and psychosocial support are auxiliary treatments14. The effectiveness and superiority of conservative treatment options like manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandages, and lymphedema garments are still controversial; they are frequently recommended in PML treatment but are expensive, labor-demanding, and long-lasting with low patient tolerance and compliance. Studies have reported the decrease of pain obtained with the use of LLLT, and that the decline in pain is greater than with other conservative treatments for lymphedema15.

It is considered that LLLT provides lymphatic collateralization by increasing the diameter and contraction ability of the lymph vessels in the damaged or untreated tissues. It was reported that LLLT stimulates the phagocytic activity of the neutrophils and monocytosis16, activates the immune system17, and has neuro-regenerative effects18. Studies have also shown that LLLT accelerates wound healing19, increases lymphatic and blood vascular regeneration20, reduces scar formation 21, and reduces the risk of skin infection via immunostimulatory effects22.

Lymphedema can occur a few months or years after the surgery. Kilbreath et al.23 conducted a prospective and large-scale study and reported that mean of these periods was found to be 18 months. In this study, the mean duration of the disease was 30 months and mean lymphedema duration was 9 months.

The lymphedema complications of postmastectomy patients should be monitored closely with clinical follow-up for at least 6 months. Patients should be evaluated in conjunction with circumferential measurements, skin findings, shoulder joint range of motion, and weight control in each examination. Identifying potential risks which can cause the disease and preventing the progression of edema are the main principles in treatment. The type of surgery for postmastectomy can be developed based on a combination of factors like axillary radiotherapy, infection, and obesity24, 25. Studies are reporting that lymphedema is twice likely to develop in patients with BMI above 3026. In this study, it was found that the patients were compatible with type 1 obesity close to the etiology of the disease.

In a large-scale study conducted by Kwan et al.27, it was determined that the incidence of lymphedema in patients after axillary dissection and/or axillary radiotherapy was 2 – 4.5 times higher. In this study, 83.3% of the patients had a history of axillary radiotherapy, 18 had modified radical mastectomy that included axillary dissection, and 6 had total mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. However, some studies show that the risk of PML increases in patients with residual nodal disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There were only 3 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of the possibility of breast-conserving surgery. According to the results of this study, it is considered that more patients must be examined to evaluate neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a risk factor28, 29.

Previous studies have shown that laser therapy in the extremity which developed lymphedema after mastectomy showed decreased volume in the first three months, and there were improvements in arm-shoulder-hand functions. The results of these studies show that LLLT has a positive effect on the developing arm lymphedema in patients with postmastectomy. In a study, the circumferential measurement was the parameter in which the best improvement was made- at a rate of 54.25% around the arm after the treatment. In this respect, a significant decrease was detected in lymphedema severity30, 31.

The LLLT improves measurable physical parameters and subjective pain scores32. Significant improvements were detected in edema, pain, and disability parameters in the affected arm. The laser is a non-invasive painless and easy-to-apply treatment method. The participants did not report any adverse effects aside from a study that informed the development of cellulite as an adverse event in LLLT patients. In this study, there were no findings in the follow-up of the patients to suggest cellulite33.

The increasing volume of limbs in lymphedema patients affects the quality of life by causing negations in external appearance, and physical and mental discomfort. The psychology and educational status of the patient change the expectations about the results of the disease. Even with individuals who have advanced-stage lymphedema and cancer, they can perceive the life expectancy and the condition differently and have different quality of life levels. In this study, when the correlation of the lower parts of the LYMQOL-Arm survey was examined, the quality of life is determined, contradicting the outcome of the clinical symptom, function, and emotional condition that are more effective than the external appearance. Although the decrease in pain, overall well-being, and functional status improved significantly with LLLT, in the study no improvements were detected in the subparameter of the emotional state containing anxiety and depressive symptoms. It was considered that even if functionality increased, and arm swelling decreased after LLLT, uncertainty about the future and the fear of recurrence of cancer affected the patients emotionally negatively. This finding suggests that lymphedema that developed after mastectomy in patients with breast cancer not only consists of arm swelling but also contains subjective symptoms and that these symptoms persist.

According to previous studies, the use of low-level laser treatment alone or together with manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandages, pressure garments, and commonly recommended decongestive treatments (like pneumatic compression), for use in the appropriate patients, is entirely rational34, 35.

In the present study, there are some limitations such as the low number of patients, the mean lymphedema duration, and the inability of patients to be followed up for long periods. On the other hand, this study cannot claim that laser therapy is the most effective method in PML. Since there are no studies that evaluate the hypothesis that LLLT can increase the risk of recurrence or metastasis, questions remain about the long-term reliability of this procedure in cancer patients.

Conclusions

As a result, this study shows that LLLT improves the quality of life in PML patients at the end of the second month. Large-scale randomized controlled studies are needed to understand the exact mechanisms of the effect of LLLT and to increase its effectiveness.

Abbreviations

BMI: Body Mass Index

Ga-As: Gallium Arsenide

LLLT: Low-Level Laser Therapy

LYMQoL: Lymphedema Quality of Life Survey

PML: Postmastectomy Lymphedema

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

Turgay and Denkçeken designed the study, prepared the manuscript, and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board (SANKO University Ethics Committee (Decision No: 2019/19.01 dated 26.12.2019)) approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin.

2018;

68

:

394-424

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lawenda BD, Mondry TE, Johnstone PA. Lymphedema: a primer on the identification and management of a chronic condition in oncologic treatment. CA Cancer J Clin.

2009;

59

:

8-24

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Shah C, Arthur D, Riutta J, Whitworth P, Vicini F. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: A review of procedure-specific incidence rates, clinical assessment aids, treatment paradigms, and risk reduction. Breast J.

2012;

18

:

357-361

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Gillespie TC, Sayegh HE, Brunelle CL, Daniell KM, Taghian AG. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: risk factors, precautionary measures, and treatments. Gland Surg.

2018;

7

:

379-403

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Morrell RM, Halyard MY, Schild SE, Ali MS, Gunderson LL, Pockaj BA. Breast cancer-related lymphedema. Mayo Clin Proc.

2005;

80

:

1480-1484

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Shaitelman SF, Cromwell KD, Rasmussen JC, Stout NL, Armer JM, Lasinski BB, et al. Recent progress in the treatment and prevention of cancer-related lymphedema. CA Cancer J Clin.

2015;

65

:

55-81

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lima MT, Lima JG, Andrade MF, Bergmann A. Low-level laser therapy in secondary lymphedema after breast cancer: systematic review. Lasers Med Sci.

2014;

29

:

1289-1295

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Omar MT, Shaheen AA, Zafar H. A systematic review of the effect of low-level laser therapy in the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer.

2012;

20

:

2977-2984

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Karadibak D, Yıldırım Y, Kara B, Saydam S. Effect of complex decongestive therapy on upper extremity lymphedema. Fizyoter Rehabil.

2009;

20

:

03-08

.

-

Borman P, Yaman A, Denizli M, Karahan S, Özdemir O. The reliability and validity of Lymphedema Quality of Life Questionnaire-Arm in Turkish patients with upper limb lymphedema related with breast cancer. Turk J Phys Med Rehab.

2018;

64

:

205-212

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology.

2013;

46

:

1-11

.

-

Pyszel A, Malyszczak K, Pyszel K, Andrrzejak R, Szuba A. Disability, Psychological Distress and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors with Arm Lymphoedema. Lymphology.

2006;

39

:

185-192

.

-

Mortimer PS. Managing lymphoedema. Clin Exp Dermatol.

1995;

20

:

98-106

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Christine M. Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lymphoedema. International consensus. London: Medical Education Partnership. 2006.

.

-

Maclellan RA. Pneumatic compression. In: Greene AK, Slavin SA, Brorson H, editors. Lymphedema Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment. Switzerland: Springer.

2015;

:

237-242

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Young S, Bolton P, Dyson M, Harvey W, Diamantopoulos C. Macrophage responsiveness to light therapy. Lasers Surg Med.

1989;

9

:

497-505

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tadakuma T. Possible application of the laser in immuno-biology. Keio J Med.

1993;

42

:

180-182

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Buchaima RL, Andreoa JC, Barravierab B, Ferreira RS, Daniela J, Geraldo VB, et al. Effect of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) on peripheral nerve regeneration using fibrin glue derived from snake venom. Injury.

2015;

46

:

655-660

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tikiz C, Angın A, Demireli P, Taneli F, Özyurt B, Tüzün Ç. Low-Level Laser Therapy is More Effective Than Pulse Ultrasound Treatment on Wound Healing: Comperative Experimental Study. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci.

2010;

30

:

135-143

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Li Y, Xu Q, Shi M, Gan P, Huang Q, Wang A, Tan G, Fang Y, Liao H. Low-level laser therapy induces human umbilical vascular endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation through activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Microvasc Res.

2019;

129

:

103959

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lee SY, Park KH, Choi JW, Kwon, JK, Lee DR, Shin MS, et al. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, and split-face clinical study on LED phototherapy for skin rejuvenation: clinical, profilometric, histologic, ultrastructural, and biochemical evaluations and comparison of three different treatment settings. J Photochem Photobiol B.

2007;

88

:

51-67

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Baxter GD, Liu L, Petrich S, Gisselman AS, Chapple C, Anders JJ, et al. Low level laser therapy (Photobiomodulation therapy) for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. BMC Cancer.

2017;

17

:

833

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM, Beith JM, Ward LC, Ung OA, Dylke ES, et al. Risk factors for lymphoedema in women with breast cancer: A large prospective cohort. Breast.

2016;

28

:

29-36

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Britton RC, Nelson PA. Causes and Treatment of Postmastectomy Lymphedema of the Arm: Report of 114 Cases. JAMA.

1962;

180

:

95-102

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hinrichs CS, Watroba NL, Rezaishiraz H, Giese W, Hurd T, Fassl KA. Lymphedema Secondary to Postmastectomy Radiation: Incidence and Risk Factors. Annals of Surgical Oncology.

2004;

11

:

573-580

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tsai RJ, Dennis LK, Lynch CF, Snetselaar LG, Zamba GKD, Scott-Conner C. Lymphedema following breast cancer: The importance of surgical methods and obesity. Front Womens Health.

2018;

3

:

10

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kwan W, Jackson J, Weir LM, Dingee C, McGregor G, Olivotto IA. Chronic arm morbidity after curative breast cancer treatment: Prevalence and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol.

2002;

20

:

4242-4248

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Specht MC, Miller CL, Skolny MN, Jammallo LS, O'Toole J, Horick N, et al. Residual lymph node disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy predicts an increased risk of lymphedema in node-positive breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol.

2013;

20

:

2835-2841

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zhu W, Li D, Li X, Ren J, Chen W, Gu H, et al. Association between adjuvant docetaxel-based chemotherapy and breast cancer-related lymphedema. Anticancer Drugs.

2017;

28

:

350-355

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Silberman H. Axillary lymphadenectomy for breast-cancer: impact on survival. In: Silberman H, Silberman AW, editors. Surgical Oncology: Multidisciplinary Approach to Difficult Problems. London: Arnold.

2002;

:

369-385

.

-

Carati CJ, Anderson SN, Gannon BJ, Piller NB. Treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema with low-level laser therapy: a double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer.

2003;

98

:

1114-1122

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Smoot B, Chiavola-Larson L, Lee J, Manibusan H, Allen DD. Effect of low-level laser therapy on pain and swelling in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv.

2015;

9

:

287-304

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Dirican A, Andacoglu O, Johnson R, McGuire K, Mager L, Soran A. The short-term effects of low-level laser therapy in the management of breast-cancer-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer.

2011;

19

:

685-690

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lau RW, Cheing GL. Managing postmastectomy lymphedema with low-level laser therapy. Photomed Laser Surg.

2009;

27

:

763-769

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Poage E, Singer M, Armer J, Poundall M, Shellabarger MJ. Demystifying lymphedema: development of the lymphedema putting evidence into practice card. Clin J Oncol Nurs.

2008;

12

:

951-964

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 7 No 9 (2020)

Page No.: 3971-3976

Published on: 2020-09-30

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

- HTML viewed - 9464 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 2033 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress