The role of anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1 (Anti-β2GP1) testing in antiphospholipid syndrome with pregnancy: A narrative review

- Public Health Laboratory Center, Palembang, Indonesia

- Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sriwijaya – Dr. Mohammad Hoesin General Hospital, Palembang, Indonesia

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sriwijaya – Dr. Mohammad Hoesin General Hospital, Palembang, Indonesia

- Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Sriwijaya, Palembang, Indonesia

- Research Division, Medhub Academy, Jakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

Anti-β₂-glycoprotein I antibodies (anti-β₂GPI) are implicated in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) pathophysiology. Testing for anti-β₂GPI is of particular importance in pregnant individuals with a high clinical suspicion of APS, who have negative lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibody results. Despite its diagnostic role, significant challenges remain in risk stratification and laboratory testing procedures, which lead to inconsistencies in clinical research and practice. The present literature review aims to summarize the importance of anti-β₂GPI testing in pregnancy-associated APS, providing a novel perspective by critically evaluating the impact of evolving assay technologies, the implications of the latest international classification criteria, and the ongoing debate surrounding non-criteria antibody isotypes. The literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, focusing on original articles published between January 2018 and December 2024. Search terms included: “anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1,” “anti-β2GP1,” “obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome,” and “pregnancy.” In summary, although anti-β₂GPI antibody testing is indispensable for the APS diagnosis, it is not without challenges, including the lack of international standardization of newer and automated assays.

INTRODUCTION

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the persistent presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs). It frequently manifests in pregnant individuals, increasing the risk of both arterial and venous thrombosis and is associated with numerous pregnancy-related complications, including recurrent miscarriage, intrauterine fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, stillbirth, and preeclampsia.1,2 Given the significant morbidity of APS in pregnancy, early and accurate detection of pathogenic aPLs is essential for appropriate management and improved maternal-fetal outcomes.3

One of the most clinically significant aPLs is the anti–beta-2 glycoprotein I antibody (anti-β2GPI), which has a well-established association with APS-related clinical manifestations. Anti-β2GPI antibodies play a key role in APS pathophysiology, promoting endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, and a hypercoagulable state. While lupus anticoagulant (LA) and anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) are core laboratory criteria for APS diagnosis, anti-β2GPI antibodies have emerged as an important biomarker for refining risk stratification.4 Elevated anti-β2GPI titers are associated with a more severe APS phenotype, including a greater likelihood of thrombotic events and obstetric complications.5,6 However, the role of routine anti-β2GPI testing in pregnancy management remains debated.

In pregnant individuals with concomitant autoimmune disorders, notably systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the presence of aPLs substantially complicates clinical management. The coexistence of SLE and APS confers a heightened risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.7 Consequently, multidisciplinary collaboration among rheumatologists, obstetricians, hematologists, and neonatologists is crucial for optimizing outcomes.8,9

Although research has investigated the role of these antibodies in predicting adverse pregnancy outcomes, study findings have been inconsistent. Despite this, emerging evidence suggests that incorporating anti-β2GPI testing into clinical practice may improve risk assessment and guide personalized therapeutic strategies.10 This is particularly relevant because understanding the predictive value of anti-β2GPI antibodies could inform therapeutic guidelines for APS management, particularly regarding the use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies such as aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), which could be tailored based on a patient’s anti-β2GPI status.3,7

This literature review aims to synthesize current evidence on the role of anti-β2GPI testing in the context of APS in pregnancy. The synthesis may provide insights into the potential clinical utility of integrating anti-β2GPI testing into existing APS diagnostic and management protocols to improve the care of pregnancy-related complications.

METHODS

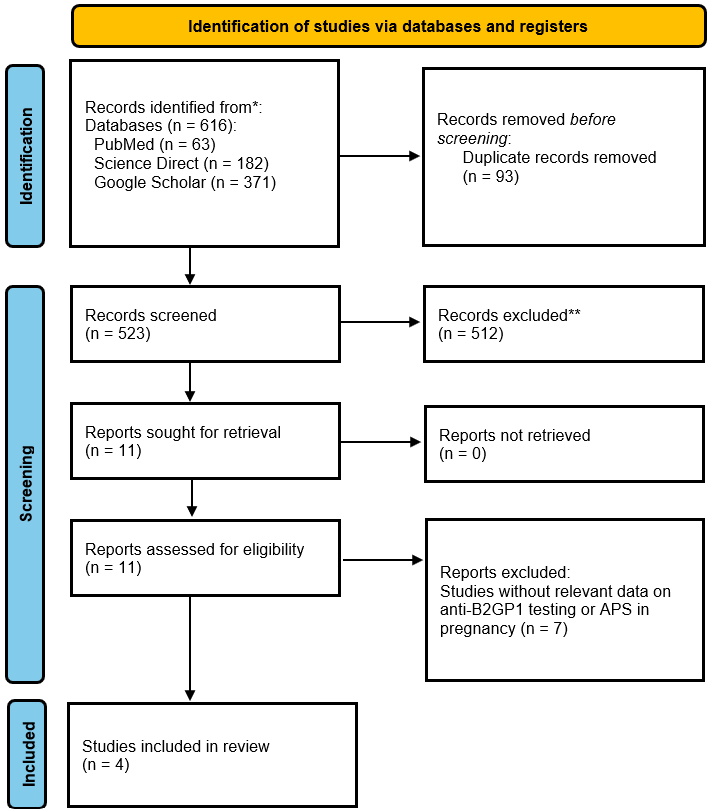

A literature search was conducted across three databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The search focused on original articles published between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2024, utilizing the predefined search terms detailed in

Systematic Search Strategy for the Narrative Review. This table details the electronic databases, search terms, and the number of records identified during the initial literature search conducted for this review (covering January 2018 to December 2024).

| Databases | Search terms | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1”[tiab] OR “anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I”[tiab] OR “anti-beta2GP1”[tiab] OR “anti-b2GP1” OR “anti-b2GPI”[tiab] OR “anti-b2GP1”[tiab] OR “beta 2-Glycoprotein I/immunology”[Mesh]) AND (“obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome”[tiab] OR “obstetric APS”[tiab] OR (“Antiphospholipid Syndrome”[Mesh] AND “Pregnancy”[Mesh])) | 63 |

| Science Direct | (“anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1” OR “anti-beta2GP1” OR “anti-b2GPI” OR “anti-b2GP1”) AND (“obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome” OR “obstetric APS” OR “pregnancy”) | 182 |

| Google Scholar | “anti-b2GPI”, “antiphospholipid syndrome” | 371 |

Study Selection Flow Diagram. This diagram outlines the systematic process used for article identification and selection in this narrative review. It details the records identified from each database (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar), the removal of duplicates, the screening of titles and abstracts against inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the final number of full-text articles assessed and included for qualitative synthesis.

Following the review process, a brief critical appraisal was performed. The methodological quality of each included study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS), as adapted for cross-sectional studies. 12 This tool, described in a prior publication, 11 was used to extract details and evaluate studies based on three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome. The evaluation employs a star system, with a maximum of 10 stars for cross-sectional studies distributed across these categories. Two independent investigators (PL and TPU) performed the assessment for each included paper.

APS ETIOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND CLASSIFICATION

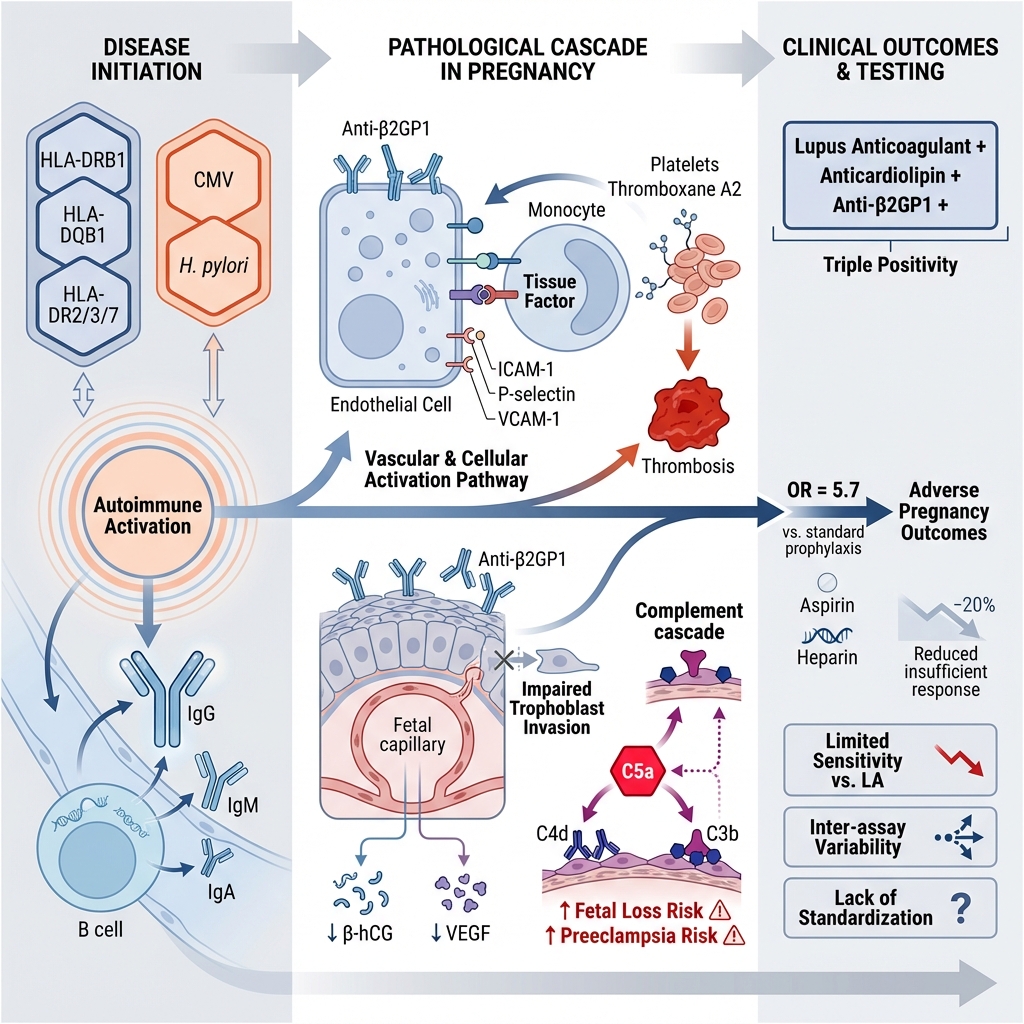

APS arises from an abnormal immune response directed against phospholipid-binding proteins, most notably β2-glycoprotein I (β2GP1). Genetic predisposition contributes to APS susceptibility, with specific human leukocyte antigen alleles—including HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DR2, HLA-DR3, HLA-DR7, and HLA-B8—being significantly associated with the disease.13 Furthermore, environmental triggers, such as viral (e.g., cytomegalovirus) and bacterial (e.g., Helicobacter pylori) infections, can induce autoantibody production and initiate an autoimmune response.14

APS affects approximately 1–5% of the general population, with a disproportionate prevalence among women due to hormonal influences. Its frequency is higher among individuals with autoimmune disorders, particularly SLE, where up to 40% of patients test positive for aPLs.15 APS is responsible for approximately 15–20% of cases of recurrent pregnancy loss.16 Additionally, one study found that among 491 patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism, 44 (9.0%) fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for APS.17 The prevalence of anti-β2GP1 positivity varies, with studies reporting rates as high as 39% in APS patients, especially those with thrombotic complications.18

APS is classified into three categories: primary, secondary, and a rare severe form termed catastrophic APS. Obstetric APS occurring in pregnant women without a pre-existing autoimmune disease is classified as primary APS. In contrast, secondary APS occurs in association with underlying conditions, most commonly other autoimmune diseases (such as SLE), malignancies, infections, or certain medications.1 Catastrophic APS (CAPS) is an acute, life-threatening condition characterized by thrombosis in small vessels affecting three or more organ systems.19

The diagnosis of APS is currently based on clinical criteria spanning six domains (microvascular, macrovascular venous thromboembolism, macrovascular arterial thrombosis, cardiac valve, hematologic, and obstetric) combined with persistent laboratory evidence of autoantibodies. Laboratory confirmation requires the persistent positivity of lupus anticoagulant in functional coagulation assays and/or the presence of IgG or IgM anti-β2GP1 and/or anticardiolipin antibodies detected by solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). In the current manuscript, obstetric APS criteria include: (1) three or more unexplained consecutive miscarriages before ten weeks of gestation and/or early fetal deaths (10 weeks to <16 weeks); (2) one or more unexplained fetal deaths at or beyond 16 weeks of gestation, without evidence of severe preeclampsia or severe placental insufficiency; or (3) delivery due to severe preeclampsia or placental insufficiency before 34 weeks of gestation, with or without associated fetal loss.20

APS PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of APS is primarily driven by the persistent presence of aPLs, particularly anti-β2GP1. These antibodies target β2GP1, a plasma protein with a five-domain structure that binds to anionic phospholipids on cell membranes.21,22 Under inflammatory or oxidative stress conditions, β2GP1 binds to phospholipids or damaged membranes and undergoes a conformational shift to an open form, exposing cryptic epitopes recognized by anti-β2GP1. This interaction initiates a cascade of pathological events involving coagulation, inflammation, and immune dysregulation.22

The thrombotic mechanism in APS involves aPL-mediated activation of multiple cellular components regulating hemostasis. Binding of anti-β2GP1 to β2GP1 on endothelial cells upregulates adhesion molecules, including intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), P-selectin, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), thereby promoting leukocyte adhesion and vascular inflammation.23 Monocytes exposed to aPLs express increased levels of tissue factor, a key initiator of coagulation, while platelets are activated to synthesize thromboxane A2, enhancing platelet aggregation. Furthermore, anti-β2GP1 impairs the function of natural anticoagulant pathways, including annexin V, antithrombin III, and the protein C and protein S system.24 These effects collectively promote a hypercoagulable state. Complement activation, particularly of C3 and C5, exacerbates vascular injury through the generation of pro-inflammatory anaphylatoxins (C3a, C5a) and the membrane attack complex (C5b-9).22 Clinically significant thrombosis rarely occurs spontaneously, supporting the "second hit" hypothesis, which posits that aPLs require an additional prothrombotic trigger—such as infection, inflammation, or trauma—to precipitate clinical events.10

Furthermore, APS is linked to accelerated atherosclerosis, a feature increasingly observed in younger patients.25 This process is driven in part by anti-β2GP1 antibodies, which form immune complexes with oxidized low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL), promoting foam cell formation and athserosclerotic plaque development.26

Pregnancy-Specific Mechanisms of Anti-β2GP1-Mediated Injury

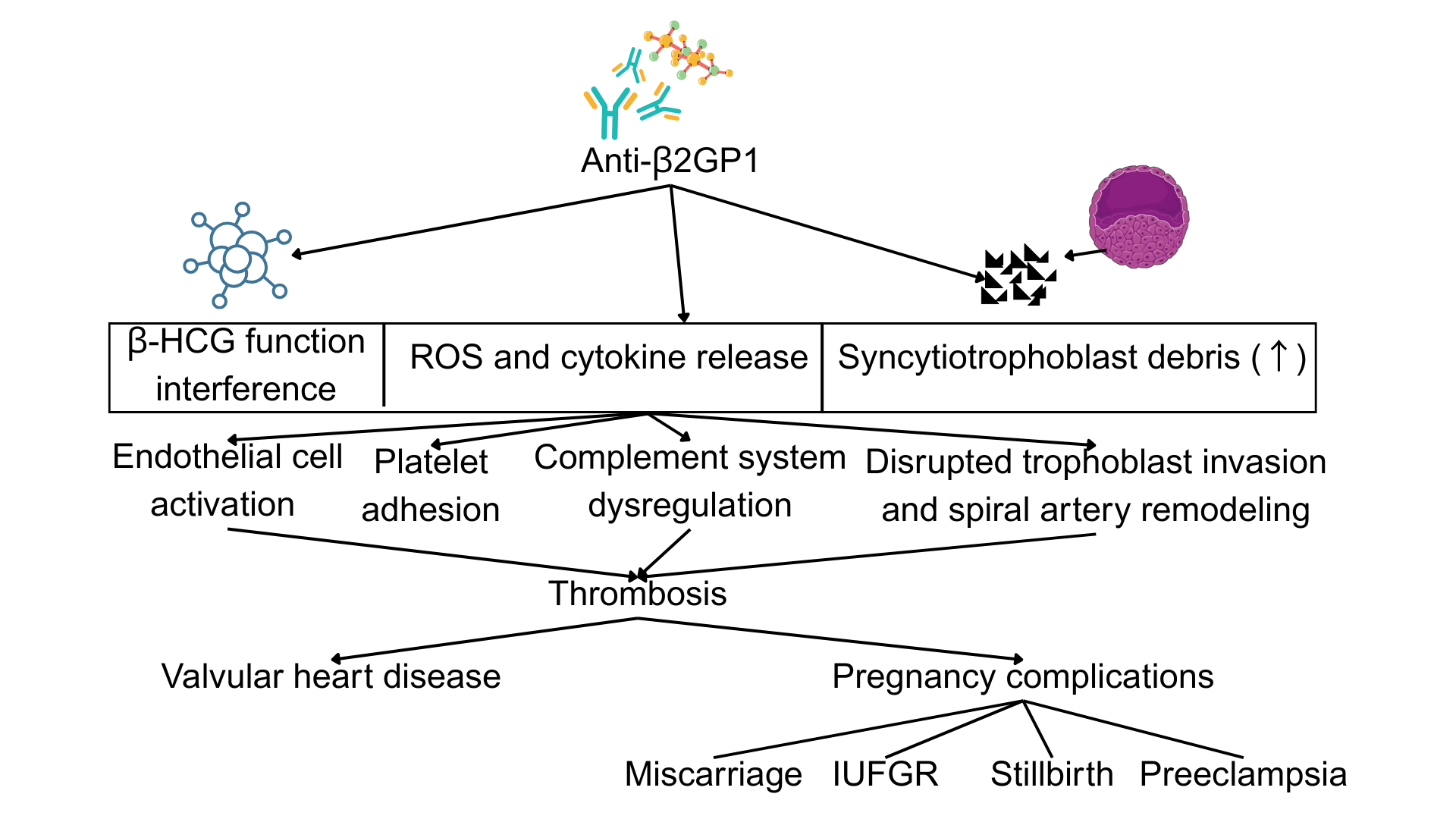

Multiple pregnancy-specific, non-thrombotic mechanisms are critical drivers of obstetric APS. Two principal mechanisms underlying placental dysfunction and adverse pregnancy outcomes following anti-β2GP1 antibody action include impaired trophoblast invasion and complement activation.

Under normal physiological conditions, trophoblasts—the primary functional cells of the placenta—constitutively express β2GP1 on their surface, a state crucial for regulating placental angiogenic equilibrium.27 This expression pattern explains why the placenta is a primary target of injury in obstetric APS. Anti-β2GP1 antibody binding hinders placental development by impairing trophoblast invasion, expansion, and migration, processes critical for spiral artery remodeling.28 Furthermore, this disruption leads to reduced synthesis of β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which are essential for maintaining normal gestation.29 Anti-β2GP1 antibodies also elicit a localized inflammatory response by activating the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MyD88 and TLR2 signaling pathways in trophoblasts, resulting in the release of multiple cytokines, including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).30,31 Moreover, these antibodies induce mitochondrial dysfunction in trophoblasts, leading to increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the release of necrotic syncytiotrophoblast debris, which activates maternal endothelial cells and exacerbates inflammation.32

The binding of anti-β2GP1 antibodies to placental tissue also triggers the complement cascade, resulting in the generation of the potent anaphylatoxin C5a.33 Complement deposition (e.g., C4d, C3b) in the placenta has been observed in APS and correlates with fetal loss and preeclampsia,34,35 thereby emphasizing the role of immune-mediated placental injury. Studies in murine models of obstetric APS have demonstrated that the pathogenic effects of aPLs are dependent on complement activation. The passive transfer of human aPLs induces fetal loss and growth restriction in wild-type mice, whereas these effects are attenuated in mice deficient in complement components C3 or C5.36 Consistently, histopathological analysis of placentas from women with obstetric APS frequently reveals deposits of complement split products, such as C4d and C3b, which serve as biomarkers of this immune-mediated injury and are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.37 Thus, complement-mediated inflammation, rather than thrombosis alone, constitutes a primary mechanism of placental failure in obstetric APS.

The immune dysregulation in APS extends beyond thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity.20 β2GP1 acts as a scaffold for pattern recognition, binding not only to phospholipids but also to microbial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), suggesting a role in innate immunity. APS patients often exhibit imbalances in lymphocyte subsets, with increased Th1 and Th17 cell populations and decreased regulatory T cells (Tregs), indicative of a proinflammatory state. Additionally, aPLs interfere with apoptotic clearance and promote neo-antigen formation on cell membranes, thereby perpetuating autoantibody production and inflammation.38 The pathogenic involvement of anti-β2GP1 antibodies in obstetric APS and the consequent clinical manifestations are illustrated in Figure 2.

Pathogenic Mechanisms Linking Anti-β2GP1 Antibodies to APS-Associated Clinical Manifestations. This schematic illustrates the primary pathological pathways through which anti-β2GP1 antibodies contribute to the clinical features of APS. Key mechanisms include: (1) endothelial cell activation and a pro-inflammatory state; (2) disruption of coagulation balance towards a hypercoagulable state via platelet activation, monocyte tissue factor expression, and impairment of natural anticoagulant pathways; and (3) pregnancy-specific placental injury mediated by impaired trophoblast function, cytokine release, and complement activation, leading to adverse obstetric outcomes such as fetal loss, preeclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

Anti-β2GP1 testing in APS patients

Anti-β2GP1 antibodies, particularly of the IgG isotype, are considered key drivers in the obstetric manifestations of APS. Evidence demonstrates a significant association between these antibodies and placenta-mediated pregnancy complications as well as an elevated thrombotic risk, including valvular heart disease.39 Notably, triple positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant [LA], anticardiolipin [aCL], and anti-β2GP1) correlates with the highest likelihood of adverse pregnancy outcomes, even despite standard prophylactic treatment with low-dose aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). 40 Thus, anti-β2GP1 antibodies contribute mechanistically and also serve as a predictive biomarker for obstetric events in APS. Several key studies on this topic are summarized in

The included studies (

Characteristics and Key Findings of Studies Evaluating Anti-β2GP1 Testing in APS Patients. This table summarizes the study design, population, assay methods, and reported thrombotic and pregnancy-related outcomes from the selected studies included in this review. Abbreviations are defined in the note below the table.

| Authors (Year) | Study Design | Subjects | Assay | Thrombotic-related Outcomes | Pregnancy-related Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perez et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | 57 thrombotic APS patients | ELISA, confirmed with BioPlex Multiplex |

The presence of β2-CIC is associated with: thrombocytopenia (OR=5.7, 95%CI:1.39−23.36) and livedo reticularis (OR=5.6, 95%CI:1.37−22.65) Participants with quadruple aPL positivity showed a higher prevalence of thrombocytopenia versus single or double positivity | N/A |

| Serrano et al. (2019) | Retrospective cohort | 151 heart transplant recipients | ELISA (INOVA) for IgA; BioPlex Multiplex for IgG/IgM |

Pre-transplant β2A-CIC associated with post-transplant thrombosis (OR=6.42,95%CI:2.1−19.63) and early mortality – at three months (HR=5.08,95%CI:1.36−19.01). β2A-CIC-positive subjects have an elevated risk of thrombotic incidents or death (73.7% vs. 16.3% - control). |

Late fetal loss (44.1%) Early fetal loss (17.6%) |

| Skeith et al. (2018) | Nested case-control | 503 cases, 497 controls | ELISA (Bio-Rad) | N/A | No significant association with composite outcome (Adjusted OR=1.48,95%CI:0.84−2.6, p=0.18). Weak association with SGA at IgG and/or IgM ≥20 units (OR=1.86, 95%CI:1.09−3.18, p=0.02). |

| Yeoh et al. (2024) | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 53 APS cases – 45 female (18 primary, 27 secondary) | N/A |

Arterial thrombosis (56.6%) Venous thrombosis (49.1%) Thrombocytopenia (26.4%). |

Early fetal loss (26.7%) Late fetal loss (33.3%) PTB (20.0%) Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (20.0%) |

The studies utilized diverse laboratory methodologies and definitions of positivity. Perez et al. and Serrano et al. employed a combination of traditional ELISA and multiplex flow immunoassays (BioPlex), 40,42 whereas Skeith et al. utilized a specific commercial ELISA kit (Bio-Rad).41 This methodological diversity is exacerbated by varying thresholds for positivity; for instance, Skeith et al. used a cut-off derived from the 99th percentile of a healthy population (≥20 GPL/MPL; where GPL is IgG phospholipid units and MPL is IgM phospholipid units),41 while a criterion of >40 GPL/MPL is frequently referenced.44 Furthermore, the shift from ELISA to automated platforms such as chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIA) seeks to enhance reproducibility. However, considerable inter-assay variation persists due to the lack of universal calibrators and standards, leading to inconsistent classification of positive results across studies and hindering the development of universal risk models.45

Second, the reported thrombotic risk varies due to differences in study population characteristics. For example, Yeoh et al. documented a high prevalence of arterial (56.6%) and venous (49.1%) thrombosis, reflecting a cohort from a single tertiary rheumatology center that predominantly comprises patients with more severe disease, many of whom have secondary APS.43

Lastly, the inherent strengths and limitations of different study designs help explain the inconsistent results regarding pregnancy outcomes. Skeith et al. conducted a nested case-control study that found no significant association between anti-β2GP1 and a spectrum of placenta-mediated complications. While this design is efficient and minimizes recall bias, its statistical power for certain outcomes may be limited, potentially obscuring true associations.41

Despite the strong association between anti-β2GP1 and APS, false-positive and false-negative results present diagnostic challenges. False-positive results may arise from transient conditions, such as viral infections, which can induce temporary autoantibody production,46 or from certain medications like hydralazine or procainamide.47 Conversely, false-negative results may occur due to low antibody titers, improper sample handling, or assay variability. To confirm sustained positivity and establish a diagnosis of APS, laboratory testing for anti-β2GP1 must be repeated at least 12 weeks after the initial positive result, and within five years of the associated clinical event.48 This step is critical, as transient antibody elevations do not constitute APS.

CLINICAL UTILITY OF ANTI-Β2GP1 TESTING FOR RISK-STRATIFIED OBSTETRIC MANAGEMENT

From a clinical pathology perspective, testing for anti-β2GP1 antibodies is an essential component of the diagnosis of APS. This assay is particularly useful in cases where lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibody tests are negative, yet clinical suspicion for APS remains high.49,50 In high-risk pregnancies, detection of anti-β2GP1 antibodies may prompt the early initiation of prophylactic anticoagulation to minimize obstetric complications. However, inter-laboratory variability in testing remains a challenge.51 Standardization of assay methods and the adoption of more sensitive detection techniques, such as chemiluminescent immunoassays and multiplex platforms, could improve reliability and reproducibility.52

Despite these challenges, anti-β2GP1 antibody testing retains significant value for APS diagnosis and risk stratification, particularly in evaluating pregnancy-related APS and thrombosis. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) guidelines utilize the antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) profile for patient categorization. A “high-risk” aPL profile, which necessitates intensive management, is defined by the presence of lupus anticoagulant, double or triple aPL positivity, or persistently high aPL titers.53 A high titer of IgG anti-β2GP1 antibodies is a key criterion for this high-risk designation and can directly influence treatment selection. For example, non-pregnant women with a history of obstetric APS and a high-risk aPL profile should receive low-dose aspirin (LDA) for thrombosis prophylaxis. During pregnancy, this regimen changes to combination therapy with LDA and prophylactic-dose heparin.53,54 Conversely, women with a history of thrombotic APS require higher, therapeutic-dose heparin during pregnancy to reduce the risk of recurrent thrombosis.55 The presence of high-titer IgG anti-β2GP1 antibodies increases the likelihood of initiating or maintaining such combination therapies to improve pregnancy outcomes.

However, a principal limitation of anti-β2GP1 antibody testing is its reduced sensitivity compared to lupus anticoagulant assays. Although highly specific, a negative anti-β2GP1 result cannot rule out APS, especially when lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies are present. A further persistent area of controversy is the clinical relevance of isolated IgA anti-β2GP1 positivity.56,57 In contrast to the well-established pathogenic roles of IgG and IgM anti-β2GP1 antibodies, the significance of IgA isotypes remains controversial, a subject of debate for over a decade. Some evidence suggests IgA anti-β2GP1 may serve as a marker for seronegative APS, where patients have clinical manifestations despite negative testing for IgG or IgM antiphospholipid antibodies.15,58 However, major international guidelines have consistently excluded IgA anti-β2GP1 from formal diagnostic and classification criteria due to a lack of standardized assays and conflicting evidence regarding its independent predictive value. The 2023 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) criteria intentionally excluded IgA isotypes to maintain high specificity and ensure cohort uniformity.20 Similarly, the 2024 British Society for Haematology (BSH) guidelines59 explicitly state that “testing for IgA aCL/aβ2GPI is not recommended for routine diagnostic use.” Consequently, while IgA anti-β2GP1 remains a relevant research topic, its unconfirmed independent utility and lack of standardized testing preclude its use in routine clinical practice, although antibodies against specific epitopes like domain 1 of β2GP1 may potentially aid in risk stratification for late pregnancy morbidity.60 Therefore, its assessment should be confined to research settings or considered only by specialists in diagnostically complex cases of suspected seronegative APS.

Future advancements in laboratory standardization, automation, and biomarker discovery may help refine the clinical utility of IgA anti-β2GP1 testing.61 Historically, diagnosis has relied on ELISAs, which exhibit significant inter-laboratory and inter-kit variability due to the lack of standardized calibrators or methodologies.62 This variability has hindered cross-study data comparisons and the establishment of universal clinical cut-off values. Recently, fully automated platforms have been developed to address these limitations, predominantly utilizing CLIA and multiplex flow immunoassay (MFI) technologies. These systems offer several advantages, including enhanced sensitivity, a broader dynamic range, improved reproducibility, and reduced manual processing time, thereby minimizing operator-dependent error.63 Recent comparative studies indicate that CLIA-based platforms provide superior diagnostic accuracy and reliability compared to conventional ELISA.64 Furthermore, incorporating functional diagnostic tests, such as thrombin generation assays or endothelial activation markers, may enable a more comprehensive assessment of thrombotic risk in individuals with APS.65 Continued research and consensus-building efforts are necessary to optimize the role of anti-β2GP1 testing in clinical decision-making and personalized patient management.

Prioritization of several key research areas is essential to advance individualized therapy in patients with obstetric APS. First, standardization of both IgA and non‑criteria laboratory assessments is required. The clinical utility of IgA anti‑β₂GP1 antibodies remains debated; while some studies suggest they may help identify “seronegative” APS patients, they are not currently recommended for diagnosis due to substantial assay variability and discrepancies among commercial kits.66 Establishing international calibration standards for IgA anti‑β₂GP1 testing is therefore essential to determine their clinical value. Second, there is a pressing need for prospective, multicenter trials to guide treatment adjustment. A significant proportion of women with obstetric APS (approximately 20–30%) still experience adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as pregnancy loss or stillbirth, despite standard treatment with low‑dose aspirin and heparin.67 Further trials should evaluate whether tailoring therapy based on specific anti‑β₂GP1 profiles—for example, using hydroxychloroquine or complement inhibitors in patients with high IgG anti‑β₂GP1 titers—can improve live‑birth rates.68,69,70 Recent studies such as the HYdroxychloroquine to Improve Pregnancy Outcome in Women with AnTIphospholipid Antibodies (HYPATIA) trial and the IMProve Pregnancy in APS With Certolizumab Therapy (IMPACT) trial exemplify ongoing research in this area.68,69 Third, integration of additional non‑criteria and functional biomarkers is crucial. The entity of seronegative APS highlights the limitations of current serological criteria. Investigation of non‑criteria antibodies, particularly those targeting the phosphatidylserine/prothrombin (aPS/PT) complex—which are associated with thrombosis and fetal death—is warranted.71 Functional assays that evaluate the biological effects of antiphospholipid antibodies, such as tests measuring annexin V resistance to assess disruption of anticoagulant shields, may provide more precise thrombotic risk stratification.24 Global hemostasis assays, including thrombin generation tests, could also aid in risk stratification and in monitoring treatment efficacy in obstetric APS.65

CONCLUSION

Testing for anti-β2GP1 antibodies is a critical element in the diagnosis and management of obstetric APS1,2. Early detection facilitates timely intervention, which can mitigate maternal and fetal risks. The presence of specific antiphospholipid antibodies, particularly high-titer IgG anti-β2GP1, is a key indicator of a high-risk APS state. Although this test enhances diagnostic accuracy, significant methodological heterogeneity across studies—including variations in laboratory assays, patient populations, and study designs—hinders the standardization of protocols. Therefore, further research is needed to refine testing methodologies and improve clinical management strategies.

ABBREVIATIONS

β2A-CIC: Circulating Immune Complexes of IgA bound to β2GP1; β2-CIC: Circulating Immune Complexes of IgG/IgM bound to β2GP1; aCL: Anticardiolipin; aPL: Antiphospholipid Antibody; anti-β2GP1: Anti-beta-2 Glycoprotein 1; APS: Antiphospholipid Syndrome; β2GP1: Beta-2 Glycoprotein I; CI: Confidence Interval; CLIA: Chemiluminescent Immunoassay; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; HR: Hazard Ratio; IgA: Immunoglobulin A; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; IgM: Immunoglobulin M; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-8: Interleukin-8; IUGR: Intrauterine Growth Restriction; LA: Lupus Anticoagulant; LDA: Low-Dose Aspirin; LMWH: Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; MFI: Multiplex Flow Immunoassay; OR: Odds Ratio; PTB: Preterm Birth; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; SGA: Small for Gestational Age; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; Th1: T Helper 1; Th17: T Helper 17; TIA: Transient Ischemic Attack; TLR: Toll-like Receptor; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; Tregs: Regulatory T Cells; VCAM-1: Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; VTE: Venous Thromboembolism

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

Study conception and idea generation: LMA, PL, and AM; data collection: LMA and TPU; analysis and interpretation of results: LMA, PL, and TPU; manuscript writing: LMA and TPU; manuscript review and editing: PL, AM, and TPU. All authors have read and agreed to the final content of the submitted manuscript.

FUNDING

None.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

DECLARATION OF GENERATIVE AI AND AI-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGIES IN THE WRITING PROCESS

The authors declare that they have used AI-assisted technologies (Quillbot and Gemini 2.5 Pro) in the writing process to improve the grammatical accuracy and readability of their paper.