Gamma-ray irradiation differentially modulates PD-1 and CTLA-4 expression and tumour growth in parental and acquired radioresistant EMT6 mouse models

- Centre for Graduate Studies, University of Cyberjaya, 63000 Cyberjaya, Malaysia

- Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Jalan Hospital, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

- Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

- Department of Surgery, Hospital Al-Sultan Abdullah, Universiti Teknologi MARA, 42300 Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

- Centre of Preclinical Science Studies, Faculty of Dentistry, Universiti Teknologi MARA, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

- Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Jalan Hospital, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

- Oncologist, Hospital Pakar Pusrawi, Jalan Tun Razak, Titiwangsa, 50400 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract

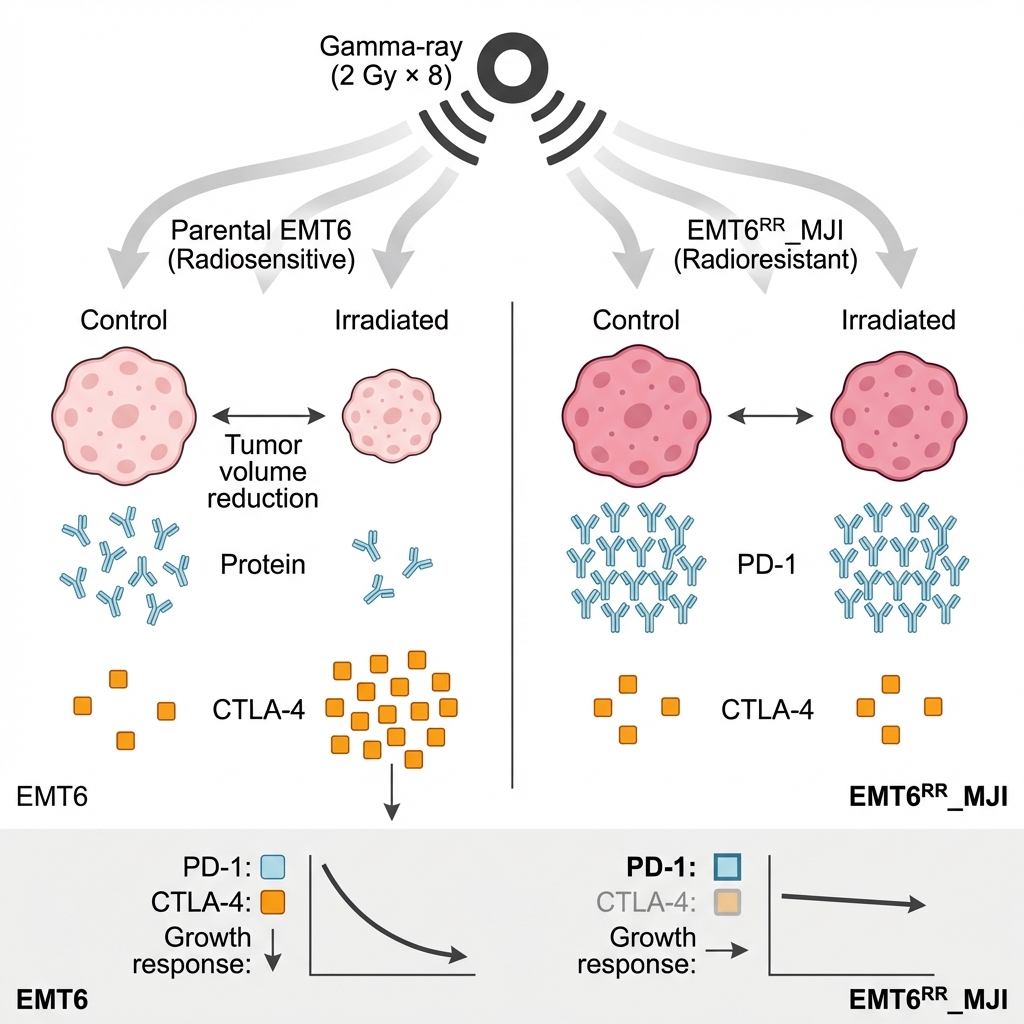

Background: Immune checkpoint proteins such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 play pivotal roles in tumour immune evasion. Our previous in vitro studies demonstrated upregulation of Pdcd1 and Ctla4 mRNA in the acquired radioresistant murine breast cancer cell line EMT6RR_MJI. This study aimed to evaluate their gene expression in vivo and assess the impact of gamma-ray irradiation on tumour progression.

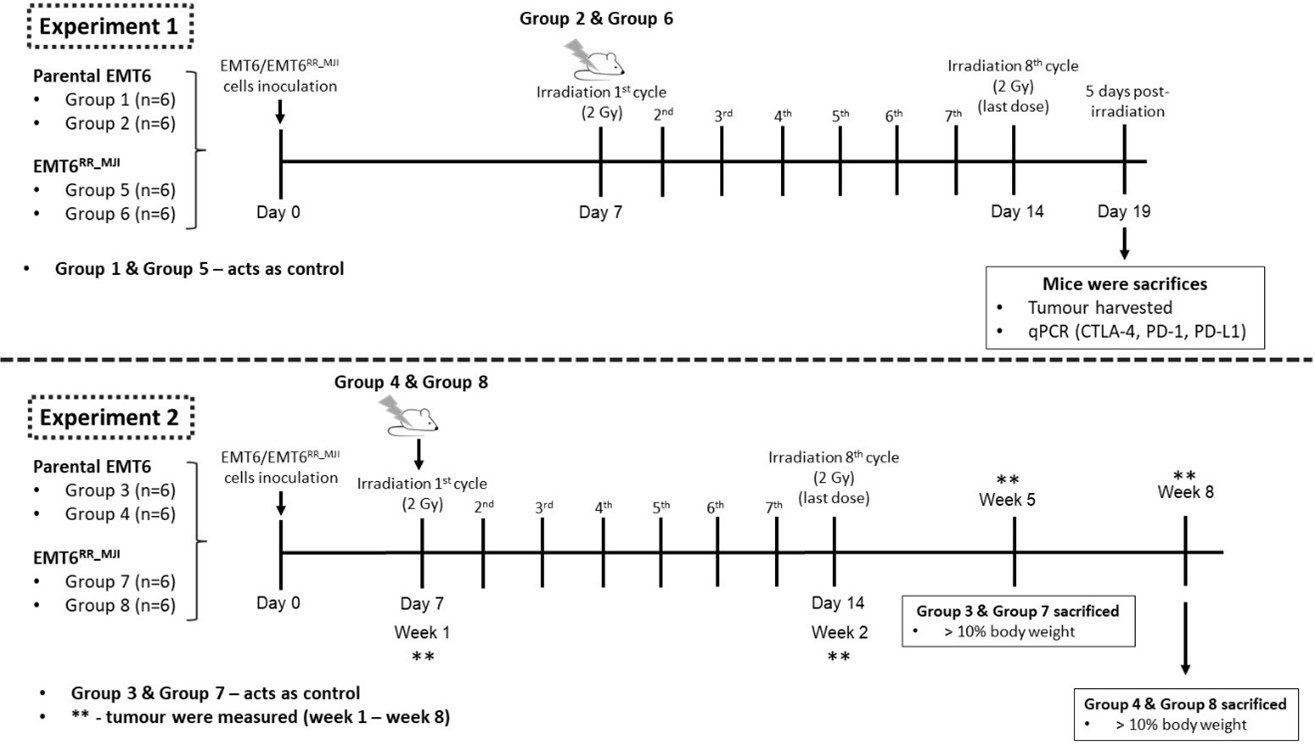

Methods: Two in vivo experiments were conducted using a mouse xenograft model subcutaneously implanted with either parental EMT6 or EMT6RR_MJI mammary carcinoma cells. In Experiment 1, levels of Pdcd1, Cd274, and Ctla4 mRNA were quantified by real-time PCR from tumours relative to control groups in both models. Mice in both control and treated groups were sacrificed on day 19 post-inoculation (5 days post-irradiation for treated groups), and tumour origin was validated by determining the expression of epithelial marker E-cadherin (Cdh1) and mesenchymal marker N-cadherin (Cdh2). In Experiment 2, tumour volume was measured weekly to assess treatment response relative to controls. Mice were sacrificed if they lost ≥10% of their body weight or showed signs of stress or ulceration.

Results: Pdcd1 expression was significantly higher in EMT6RR_MJI tumours compared to parental EMT6 tumours (p<0.0001), with no significant difference observed for Ctla4. Gamma-ray irradiation reduced Pdcd1 expression in EMT6RR_MJI tumours (p<0.01) but not in EMT6. Conversely, Ctla4 expression increased significantly in irradiated EMT6 tumours (p<0.01) but remained unchanged in EMT6RR_MJI. Tumour growth was markedly faster in EMT6 tumours than in EMT6RR_MJI tumours from week 2 onward (p<0.0001). Irradiation significantly reduced tumour volume in EMT6 tumours at weeks 3 (p<0.01), 4, and 5 (p<0.001), while EMT6RR_MJI tumours showed no reduction.

Conclusion: Gamma-ray irradiation differentially modulated Pdcd1 and Ctla4 expression in radioresistant (EMT6RR_MJI) and parental (EMT6) tumour models. The absence of tumour reduction in EMT6RR_MJI tumours suggests inherent radioresistance. These findings provide preliminary insights into the link between immune checkpoint regulation and radiation response in breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer remains one of the leading threats to human health and is associated with a reduction in life expectancy. Studies have shown that the prevalence of cancer and mortality rates are rising worldwide, as per a recent report from the Global Cancer Report, which indicated that approximately 14 million new cases were diagnosed in 2022 1. Additionally, the report projected that cancer cases will increase by up to 60% over the next 20 years 2. Advances in early detection, screening, diagnosis, and treatment have contributed to a modest decline in cancer mortality 3; however, comprehensive worldwide cancer data indicate that further research is needed to reduce cancer mortality 3,4. Cancer treatment involves a variety of approaches, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, stem cell transplantation, and multidisciplinary strategies 5.

Radiotherapy (RT) primarily induces DNA damage, leading to activation of the DNA damage response (DDR). The intricate DDR pathway maintains genome stability by activating proteins responsible for detecting, signaling, and transmitting damage signals to effector proteins that regulate cell cycle progression, arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis; this is one of the biological effects of ionizing radiation (IR) on normal cell function 6. Over half of cancer patients undergo RT, with at least 40% experiencing clinical benefits. However, treatment resistance remains a significant obstacle that reduces the effectiveness of radiotherapy 7. Various signaling pathways linked to tumour development have provided deeper insights into cancer biology, leading to the development of new targeted therapies. Multiple signaling pathways, including the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/AKT), JAK/STAT, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), Wnt, and NF-κB signalling pathways, are often interconnected in cancer research. Numerous studies have found that alterations in the PI3K/AKT pathway are commonly linked to cellular transformation, carcinogenesis, cancer development, and treatment resistance 8. In our previous study, we reported an increase in and expression, which may contribute to acquired radioresistance in an in vitro model via the PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT pathways 9. Research has shown that the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway is frequently overactivated in cancer cells resistant to radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy 10. Additionally, evidence suggests that dual targeting of PI3K and mTOR may reduce radiation resistance in various cancer cell types, both in vitro and in vivo xenograft models 11.

The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway has been proposed to play a key role in the development of radiotherapy resistance, making it a promising target for further investigation. This pathway regulates several hallmarks of cancer, including cell survival, metastasis, and metabolism. It is also involved in tumour microenvironment remodeling, affecting angiogenesis and recruitment of inflammatory cells 12. A variety of chromosomal alterations, such as mutations in PIK3CA, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), AKT, TSC1, and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), can lead to abnormal activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway 13. The PI3K/AKT pathway is frequently mutated and activated in cancer 14.

The Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway is another critical signalling pathway involved in cellular responses to cytokines and growth factors 15. The JAK/STAT pathway has been identified as mediating resistance to radiotherapy in various cancers 16. While acquired resistance arises from activation of alternative signalling pathways, de novo resistance results from genetic changes in receptors or downstream signalling molecules in the JAK2/STAT3 pathway 17. Previous studies have highlighted the JAK/STAT pathway as a crucial mediator of radioresistance 16.

The PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT pathways play important roles in mediating cellular responses to radiation and immune checkpoint blockade. Crosstalk between these pathways and CTLA-4 signaling can influence tumour radioresistance and immune evasion, thereby impacting the efficacy of radiation therapy and immunotherapy. Understanding the interplay between these pathways is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies to overcome treatment resistance and improve patient outcomes in cancer.

Building on our previous findings (Sham et al., 2023), which reported increased and expression in the radioresistant EMT6 cell line, the present study extends this work into an in vivo setting to examine whether similar immune-checkpoint modulation occurs in the whole-tumour microenvironment. Although the EMT6 model shares features with the existing –EMT6 models, it represents a stably acquired, fractionation-induced radioresistant phenotype, offering an opportunity to compare immune-regulatory responses between resistant and non-resistant tumours. By assessing radiation-associated changes in immune-checkpoint expression in this more physiologically relevant context, the study provides additional insight into how tumour–immune interactions may influence radioresistance and could inform future strategies combining radiotherapy with immunomodulatory approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

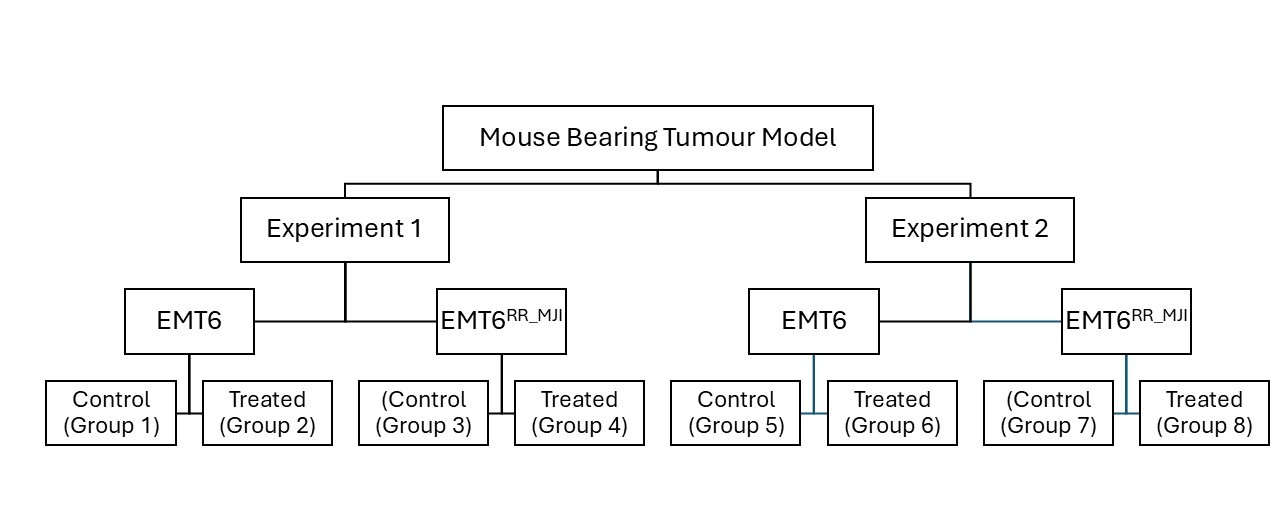

This study consisted of two experiments. Experiment 1 assessed the expression levels of , and in control and treatment groups from both EMT6 and EMT6 tumour-bearing mouse models at 5 days post-irradiation (acute phase). Tumour identity was confirmed by evaluating the expression of the mesenchymal marker () and the epithelial marker (). Experiment 2 evaluated the impact of gamma-ray irradiation on tumour progression in both models for up to 35 weeks post-inoculation, until tumours reached 10% of body weight, or until mice exhibited signs of distress or ulceration (Figure 1).

Study design of the mouse-bearing tumour models. The study consisted of two experimental phases: Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, each involving EMT6 (parental) and EMT6RR_MJI (radioresistant) tumour-bearing mouse models. In each experiment, mice were divided into control and treated group

Cell lines

EMT6 cells were procured from ATCC, while EMT6 cells were derived from radioresistant sublines selected from EMT6 lines by subjecting them to 2 Gy gamma-ray irradiation in eight fractions, as described by Sham . (2023) 9. Both cell lines were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were detached using Accutase during passaging. Both cell lines were of the same passage number.

Animal model and cell inoculation

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Research Ethics Committee (REC) ethical guidelines, following the ARRIVE 2.0 recommendations, and were approved (Ethical Approval No. UITM CARE 316/2020). Prospective sample-size calculation (n=6 per group) was performed based on preliminary data using a power analysis (α=0.05, power=0.8). Forty-eight healthy female BALB/c mice (18–22 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Facility (LAFAM), Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Puncak Alam, and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were acclimatized to handling procedures prior to experimentation. Mice were randomly assigned to groups using simple randomisation to minimise selection bias. Tumour-bearing mouse models were established as described by Ibahim . (2016) 18. Mice were shaved on the left hind legs before inoculation. The BALB/c mice were randomised into eight groups, with four groups receiving inoculation with either 1 × 106 = 10 proliferative EMT6 or EMT6 cells. Each tumour-bearing model comprised two subgroups: control (Groups 1, 2, 5, 6) and treatment (Groups 3, 4, 7, 8) per experiment. For Experiment 2, tumour growth was monitored until week 5 post-inoculation in control groups and until week 8 in treatment groups (Figure 2). Humane endpoints were applied throughout the study, including euthanasia when tumour size exceeded 10% of body weight, showed signs of ulceration, or displayed physical distress.

Experimental timeline of EMT6 and EMT6RR_MJI tumour-bearing mouse models following gamma-ray irradiation. Experiment 1 examined the acute phase response, where EMT6 and EMT6RR_MJI tumour-bearing mice received eight cycles of 2 Gy irradiation starting on Day 7, and tumours were harvested five days after the final dose for qPCR analysis of

Animal irradiation

Tumours on the mice’s hind legs underwent irradiation using the Gamma Cell 220 Excel (MDS NORDION/GC 220 E) at the Department of Nuclear Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. In all treatment groups of Experiments 1 and 2, irradiation commenced on day 10 post-inoculation, delivering 2 Gy per fraction for eight consecutive fractions. Before irradiation, mice were anaesthetised via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine. Each mouse was positioned on its side, with the tumour secured in a strainer and placed within a dedicated lead shield during the irradiation procedure 19. Post-irradiation, anaesthesia recovery was closely monitored, and mice were returned to their cages.

Tumour collection

In Experiment 1, mice in both control and treatment groups were euthanized at five days after the final irradiation dose using cervical dislocation. In Experiment 2, control group mice were euthanized when the tumour exceeded 10% of body weight, while treatment group mice were euthanized at week 8 post-inoculation (Figure 2). Euthanasia was performed by intraperitoneal administering of a mixture of ketamine and xylazine at a dose of 0.1 ml per 10 g body weight. Once unconscious, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and tumours were promptly excised and weighed. Tumour samples were then stored at -80°C for further analysis.

RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from tumour samples of mice using a Macherey–Nagel RNA extraction kit (MN, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was quantified and purity was assessed for contamination using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Reverse transcription and cDNA synthesis, one-step qPCR, were performed using the Bioline SensiFAST™ SYBR® No-ROX kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Bioline, UK). Gene expression analysis of the selected genes (, and ) was conducted using the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). The qPCR reaction mixture composition and thermal cycling conditions are listed in

The composition of qPCR mix per reaction

| Components | Volume | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|

| 2x SensiFAST™ SYBR® No-ROX One-Step Mix | 10 µL | 1x |

| Forward Primer | 0.8 µL | 400 nM |

| Reverse Primer | 0.8 µL | 400 nM |

| Reverse transcriptase | 0.2 µL | - |

| RiboSafe RNase Inhibitor | 0.4 µL | - |

| H2O | 3.8 µL | - |

| Template | 4 µL | - |

| Final volume | 20 µL |

List of cycle steps in qPCR

| Step | Temperature | Time | Number of cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse transcription | 45°C | 10 minutes | 1 |

| Polymerase activation | 95°C | 2 minutes | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95°C | 5 seconds | 40 |

| Annealing | 60°C | 10 seconds | 40 |

| Extension | 72°C | 5 seconds | 40 |

The forward and reverse primer sequences for the selected genes

| NCBI gene ID | Genes | Primer | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 56249 | Forward | 5’-3’ ATGACCCAAGCCGAGAAGG | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ CGGCCAAGTCTTAGAGTTGTTG | ||

| 14433 | Forward | 5’-3’ AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA | ||

| 60533 | Forward | 5’-3’ GCTCCAAAGGACTTGTACGTG | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ TGATCTGAAGGGCAGCATTTC | ||

| 18566 | Forward | 5’-3’ACCCTGGTCATTCACTTGGG | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’CATTTGCTCCCTCTGACACTG | ||

| 12477 | Forward | 5’-3’ TTTTGTAGCCCTGCTCACTCT | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ CTGAAGGTTGGGTCACCTGTA | ||

| 12550 | Forward | 5’-3’ CAGGTCTCCTCATGGCTTTGC | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ CTTCCGAAAAGAAGGCTGTCC | ||

| 12558 | Forward | 5’-3’ CTCCAACGGGCATCTTCATTAT | |

| Reverse | 5’-3’ CAAGTGAAACCGGGCTATCAG |

Tumour measurement

Once tumour growth was detected, the width and length of the tumour were measured three times using a digital calliper. Prior to each measurement, the fur around the left hind leg was shaved to facilitate the process. The mean width and length of the tumour were then utilized to calculate the tumour volume using the following equation adapted from a previous study 21.

Statistical analysis

Multiple endpoints were evaluated in this study. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 8 using t-tests and one-way ANOVA with significance set at p < 0.05. Although more appropriate methods—such as multiple-comparison corrections (e.g., Holm–Šidák) and repeated-measures analyses for longitudinal data—would normally be required, the raw dataset is no longer available for re-analysis. Results should therefore be interpreted with caution, and this limitation has been clearly acknowledged.

RESULTS

Confirmation of tumour development derived from EMT6 cells.

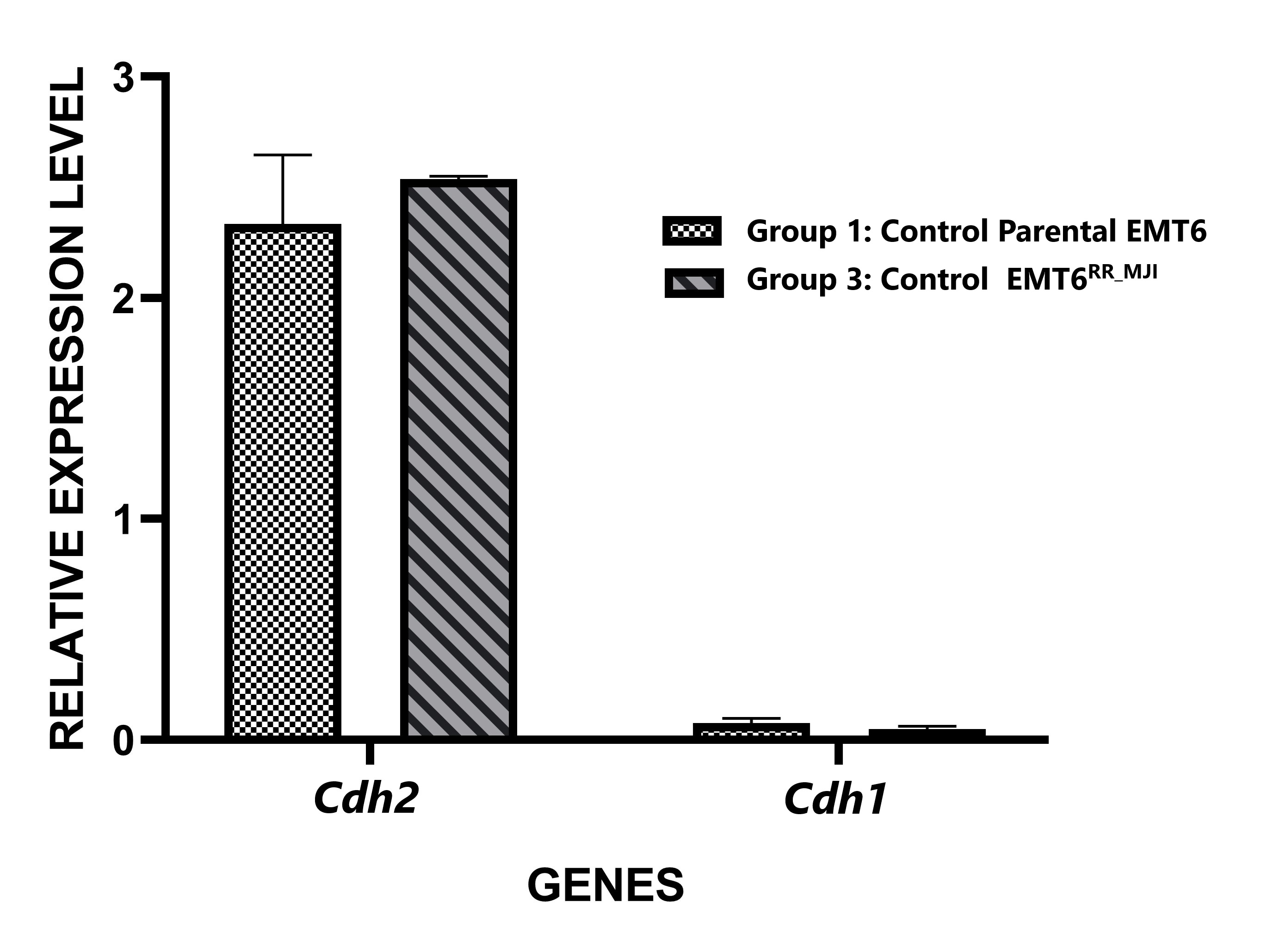

Through analysis of and gene expression in tumour sections, tumour development was confirmed to originate from parental EMT6 or EMT6 cells. The overexpression of and downregulation of served as a characteristic marker of EMT cell proliferation (Figure 3). Consistent results were observed in tumour tissues derived from both parental EMT6 and EMT6 cells, suggesting that the proliferative state of EMT cells contributes to the formation of both tumour tissues.

Relative expression levels of

increases in EMT6 untreated mouse bearing tumour model.

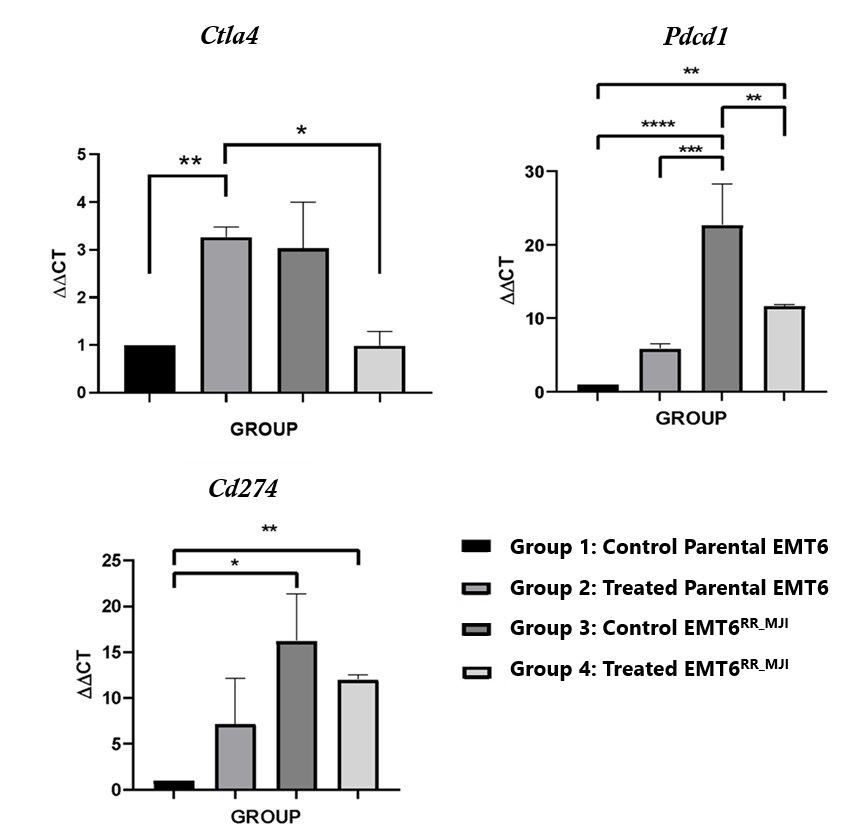

Based on our data, the activation of radioresistance in EMT6 cells was hypothesized to be mediated by and . The potential link between and with radioresistance was confirmed by investigating the expression of CT and in tumour sections of EMT6 -and parental EMT6-treated groups five days post-irradiation compared to the respective control groups.

There was a significant increase in (****p<0.0001) and PD-L1 (p<0.05) expression in the EMT6 control group at the initial time point compared to parental EMT6 cells, while no significant difference was observed in expression. In the parental EMT6-treated group, expression was significantly higher than in the control group (p<0.01), but there were no significant changes in and expression. In contrast, in the EMT6 groups, the expression of PD-1 was significantly reduced in the treated group compared to the control group (p<0.01). Although and expression showed a decreasing trend, no significant changes were observed. Interestingly, the expression levels of and in the EMT6-treated group were significantly higher than those in the parental EMT6 group. These findings suggest that exposure of the parental tumour to gamma-ray irradiation led to an increase expression, as observed in the acquired radioresistance EMT6 (Figure 4).

Effects of gamma-ray post-irradiation on

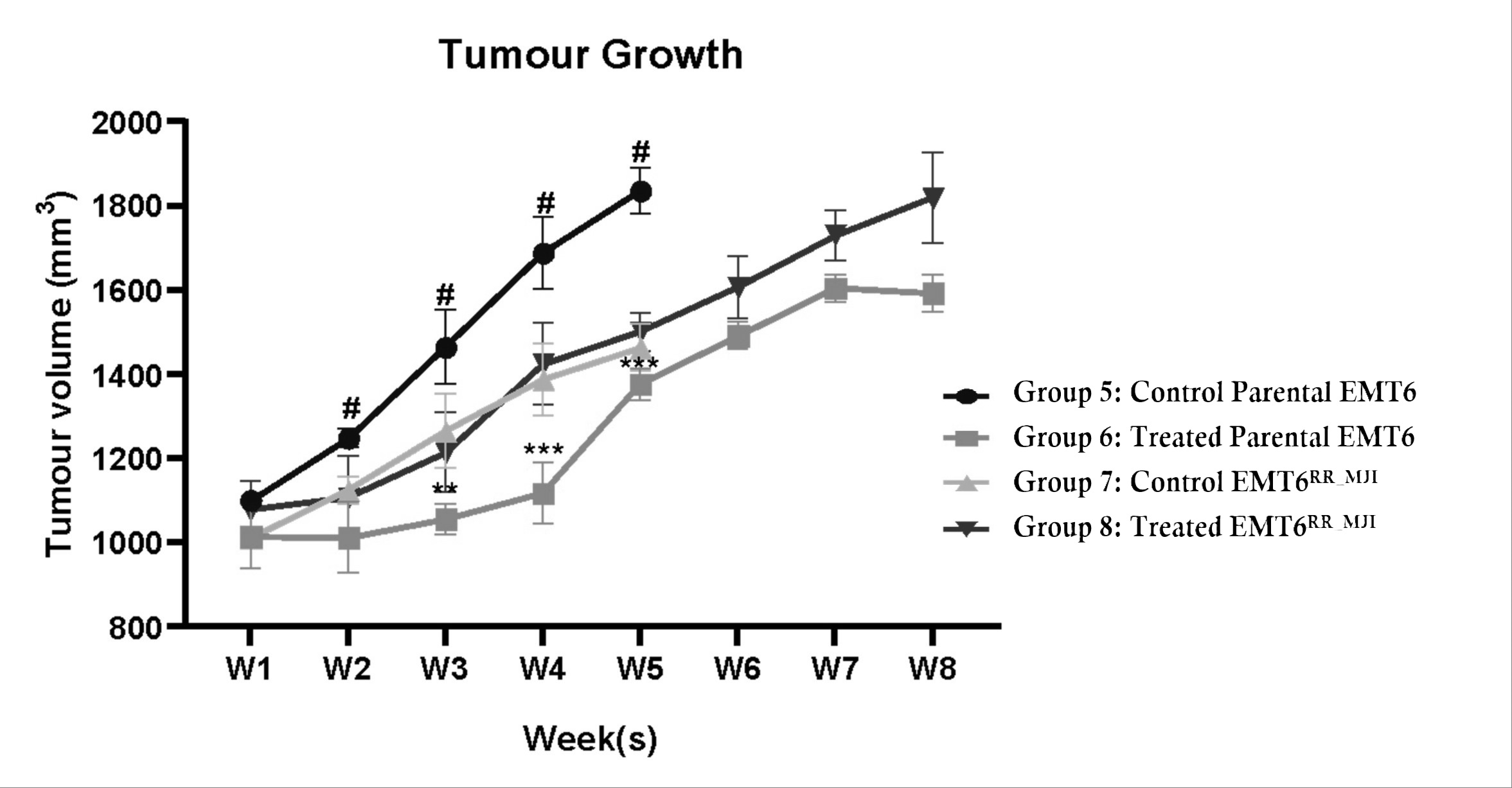

Tumour growth was reduced in the treated parental EMT6 but not in the EMT6 mouse-bearing tumour model

Tumour growth in mice bearing parental EMT6 and EMT6 control groups was fully accelerated until week five. The tumour volume in the parental EMT6 group was higher than that in the EMT6 control group beginning from weeks two until five (#p<0.0001). Mice from both groups were sacrificed after week five because their tumour volume was more than 10% of their body weight. After eight days of fractionated radiation treatment in both models, tumour growth increased in both groups. The tumour growth in the treated-parental EMT6 group was significantly regressed compared to the control from weeks three to five (**p<0.01 at week 3, ***p<0.001 at weeks 4 and 5). However, in the EMT6 group, despite receiving treatment, the tumour volume was not different from that of the control group, indicating that the cells were radioresistant (Figure 5).

Progression of tumour growth in mice injected with either parental EMT6 or EMT6RR_MJI cells for up to 8 weeks. Despite the increase in tumour growth in mice injected with EMT6RR_MJI cells compared to the other groups, no significant difference was observed compared to the control EMT6RR_MJI group. #p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, (n=6, mean ± s.d).

DISCUSSION

This study extends our previous in vitro observations (Sham et al., 2023) by confirming, for the first time in vivo, that and are differentially regulated in radioresistant versus parental EMT6 tumours following gamma-ray exposure. While prior murine breast cancer models of radioresistance have focused largely on DNA repair, apoptosis, and signalling pathways, our findings introduce a novel immunoregulatory dimension to the mechanism of radioresistance. The divergent modulation of PD-1 expression between resistant and non-resistant tumours indicates that immune checkpoint adaptation may represent a key distinguishing feature of the radioresistant phenotype. This not only enhances mechanistic understanding but also identifies PD-1 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in resistant breast cancer.

Furthermore, by integrating checkpoint profiling with tumour growth analysis, this study establishes a comprehensive in vivo platform for evaluating radio-immunomodulatory interactions—an aspect largely absents from prior murine breast cancer models. The work therefore provides both conceptual and methodological novelty that extends beyond our previous in vitro research and contributes meaningfully to the evolving framework of radio-immunobiology.

This study did not include an a priori power analysis, and the use of six mice per group may have reduced the power to detect small to moderate effects, particularly in gene expression analyses where inter-individual variability can be substantial. The findings should therefore be interpreted with caution, and validation using larger sample sizes and appropriately powered experimental designs is recommended for future work.

Cancer metastasis remains a leading cause of cancer-related death, with primary tumour cells spreading by infiltrating blood vessels, invading the surrounding microenvironment, and migrating to distant organs to form secondary tumours 22. A key process driving metastasis in many epithelial cancers is the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), where cancer cells undergo genetic reprogramming, transforming from a non-motile, epithelial phenotype to a more migratory, mesenchymal-like phenotype. This transformation enhances the tumour’s malignancy and invasiveness 23. A hallmark of EMT is the downregulation of epithelial cadherin gene (), and upregulation of neural cadherin gene () 24. E-cadherin and N-cadherin proteins are calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules that regulate cell–cell adhesion and migration and tumour invasiveness. Loss of E-cadherin–mediated adhesion plays a vital role in the progression of epithelial tumours from benign to invasive forms 25. Successful creation of the xenograft model using EMT6 cells was confirmed analysing the expression of the and epithelial markers. was upregulated, whereas the was downregulated. serves as a marker for mesenchymal cells 26, whereas is a marker for epithelial cells 26. Therefore, the overexpression of and downregulation of support the idea that the radioresistant tumour originated from EMT6 cells.

PD-1 proteins and its ligand, PD-L1 which are part of the immunoglobulin superfamily, serve as crucial inhibitory checkpoint proteins that regulate T cell signalling. In resting immune cells, expression is low 27. However, overexpression helps tumour cells evade cytotoxic T lymphocytes and the development of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies has become a central focus of cancer immunotherapy 28. Overexpression of has been shown to predict clinical outcomes in patients with low-grade glioma following radiotherapy 29, and its role in immune response modulation is further evidenced by the development of autoimmune diseases in mice lacking expression. Among breast cancer patients, a significant proportion (55-59%) exhibit overexpression of mRNA 30. According to Chen et al. (2016), PD-L1 activates an inhibitory signalling pathway that prevents T cell activation 31. This blocked immune-mediated cell death allows tumour cells to proliferate and survive within the tumour microenvironment 32 contributing to treatment resistance. PD-1 and PD-L1, as well as the CTLA-4 immune checkpoint pathways help maintain peripheral tolerance by reducing T cell activation. Cancer cells utilize these pathways to create an immunosuppressive environment, enabling tumour growth and proliferation rather than immune system destruction 33. These findings align with these current studies, which showed increased and expression in the EMT6 tumour model.

CTLA-4 is a cell-surface receptor protein that inhibits T cells from transmitting immunological signals 34. It functions alongside regulatory T cells (Tregs) as part of a complementary, overlapping immune tolerance mechanisms. The suppressive activity of Tregs is reduced when mRNA expression is impaired 35,36. CTLA-4 competes with its homolog CD28 for binding to the ligands CD80/CD86, thereby interfering with CD28-mediated T cell activation and decreasing the immune response 37. Overexpression of in four different breast cancers and tumorigenic cell lines suggests its role in resistance to radiotherapy 38. Accordingly, overexpression has been linked to poor survival outcomes in patients with breast cancer 38. Interestingly, a better prognosis has been associated with overexpression in tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), highlighting the critical role of CTLA-4 protein in helping tumours escape immune responses 30,39.

Radioresistance in cancer cells can be affected by various mechanisms, including reoxygenation, DNA repair, apoptosis, and proliferation 40. The current study employed a fractionated radiation dose to allow tumour reoxygenation between fractions, thereby increasing tumour sensitivity to radiotherapy 41. The results indicated that mice with radioresistant EMT6 cells (EMT6) were unaffected by irradiation, whereas parental EMT6 tumours undergoing fractionated irradiation showed growth regression. A previous study showed that higher radiation doses with fewer fractions (10 Gy/ 2 fraction per week) could reduce tumour growth, increase anti-tumour immunoreactivity, and limit delayed radio-necrosis 42. Accordingly, mesenchymal stem cells restrict growth and promote apoptosis by inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells 43. Mesenchymal cells also improve the effects of radiotherapy on malignancies, most likely by reducing tumour cell proliferation and enhancing cancer cell death 44. Taken together, the regression of tumours in the treated parental EMT6 cell model was due to (i) higher fractional irradiation doses that increased tumour control and immunoreactivity, as well as (ii) the presence of mesenchymal cells in the tumour.

The contrasting responses between parental EMT6 and EMT6 cells suggest potential mechanisms like post-radiotherapy hypoxia and early acquisition of radioresistance in the latter 41. A previous study reported that the effectiveness of radiotherapy in hypoxic tumours decreases as cancer cells adapt to hypoxic conditions and become more resistant to radiation 45. Tumour cells may escape the radiation effects by migrating and penetrating the vessels. Although this study did not measure hypoxic markers, it has been shown that irradiation can cause hypoxia in tumours which hampers immune cells and causes immune suppression and poor prognosis after radiation therapy 46. Irradiation induces radioresistance in cancer cells of EMT tumours through multiple signalling pathways and the tumour microenvironment (TME) 47. Fractionated irradiation can upregulate mRNA expression and cause changes in the tumour microenvironment 48. This is consistent with the results of the present study, where EMT6 tumour cells showed increased and expression, resulting in increased tumour growth after irradiation. Targeting these markers might enhance the radiosensitivity in tumour tissue. Another factor is the presence and increase of EMT cells in tumours, which promotes cancer-associated fibroblast formation in tumours. Radiation-induced mesenchymal transition can lead to the abnormal recruitment of pericytes in the tumour vasculature during tumour regrowth after radiotherapy 49. Radiation-induced mesenchymal transition, observed in EMT6 cells, contributes to acquired radioresistance, emphasizing the importance of inhibiting this process to enhance radiotherapy efficacy, mainly through immune response promotion. 50.

CONCLUSION

expression was elevated in the acquired radioresistant EMT6 cells, with gamma-ray irradiation resulting in a reduction of levels. In contrast, and expression were lower in parental EMT6 cells but increased following irradiation. Gamma-ray irradiation did not significantly affect tumour volume in the EMT6 model, likely reflecting the inherent resistance of these cells. Overall, this study provides preliminary evidence suggesting that radiation may modulate immune checkpoint expression differently in resistant and non-resistant tumour models. These findings highlight potential interactions between immune regulation, radiation response, and tumour microenvironment dynamics that warrant further mechanistic and functional investigation.

Abbreviations

AKT: Protein kinase B; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; ARRIVE: Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; BALB/c: Bagg Albino laboratory-bred mouse strain; cDNA: Complementary DNA; CD28: Cluster of differentiation 28; CD80/CD86: Cluster of differentiation 80/86; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; DDR: DNA damage response; DMEM: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid; EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; EMT6: Acquired radioresistant EMT6 subline; FBS: Fetal bovine serum; FIG: Figure; Gy: Gray (unit of radiation dose); IR: Ionizing radiation; JAK: Janus kinase; LAFAM: Laboratory Animal Facility; mRNA: Messenger RNA; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PD-1: Programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog; qPCR: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction; REC: Research Ethics Committee; RNA: Ribonucleic acid; RT: Radiotherapy; STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription; TGFβ: Transforming growth factor beta; TILs: Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes; TME: Tumour microenvironment; Tregs: Regulatory T cells; UiTM: Universiti Teknologi MARA

Acknowledgments

The study was partly funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme, Ministry of Education Malaysia (FRGS/1/2019/SKK08/UITM/02/9) and Lestari Research Grant, Universiti Teknologi MARA (600-RMC/MYRA 5/3/LESTARI (094/2020)).

Author’s contributions

Funding acquisition: MJI, NAH, HHH

Conception: NRFS, MJI

Methodology: NFRS, NAH, MJI

Interpretation or analysis of data: NRFS, NAHH, MJI

Preparation of the manuscript: NH, NAHH, NH, WNIWMZ, MKAK, SBSAF, SO, NJO, MJI

Revision for important intellectual content: NFRS, HHH, NAHH, SO, NJO, SBSAF, EO, MJI

Supervision: NAHH, HHH, MKAK, MJI

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Raw Ct files and individual tumour-volume datasets are unavailable due to historical data-storage limitations. However, all processed data used for analyses are fully presented in the manuscript and supplementary materials, and additional information can be provided upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with Research Animal Ethic Committee UiTM (UITM CARE: 316/2020) guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother for publication of this Case Report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that generative AI tools were used solely to improve the clarity and language of selected sentences in the manuscript. The use of AI was limited to linguistic refinement and did not involve the generation of scientific content or data analysis. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy, originality, and integrity of the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.