A Caco-2 and Bifidobacterium bifidum co-culture model to assess lapatinib’s effects on intestinal microbiota and cell viability

- Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sg Buloh Campus, Jalan Hospital, 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

- National Public Health Laboratory Sungai Buloh Lot 1853, Kampung Melayu 47000 Sungai Buloh, Selangor Malaysia

Abstract

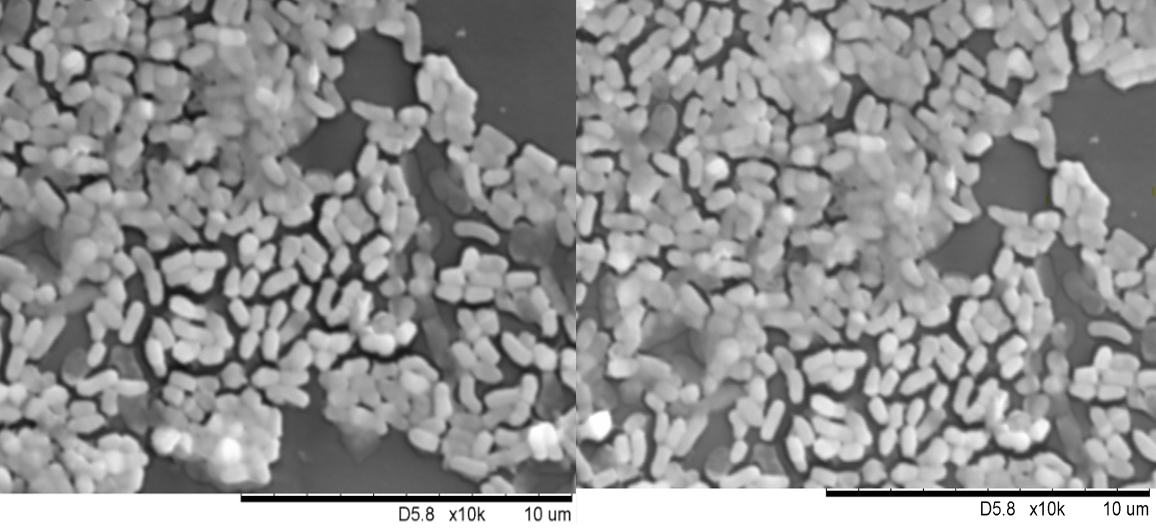

Background: Lapatinib (LAP), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) used to treat ErbB2-overexpressing breast cancer, is frequently associated with diarrhoea reported in 58–78 % of patients. Decreased Bifidobacterium spp. levels in TKI-treated patients have been observed, suggesting a link between LAP and gut microbiota alterations, but the underlying interactions remain unclear. The present study established a Caco-2/Bifidobacterium bifidum (BB) co-culture model to examine the effects of LAP on intestinal epithelial cell viability, bacterial viability, and bacterial adhesion.

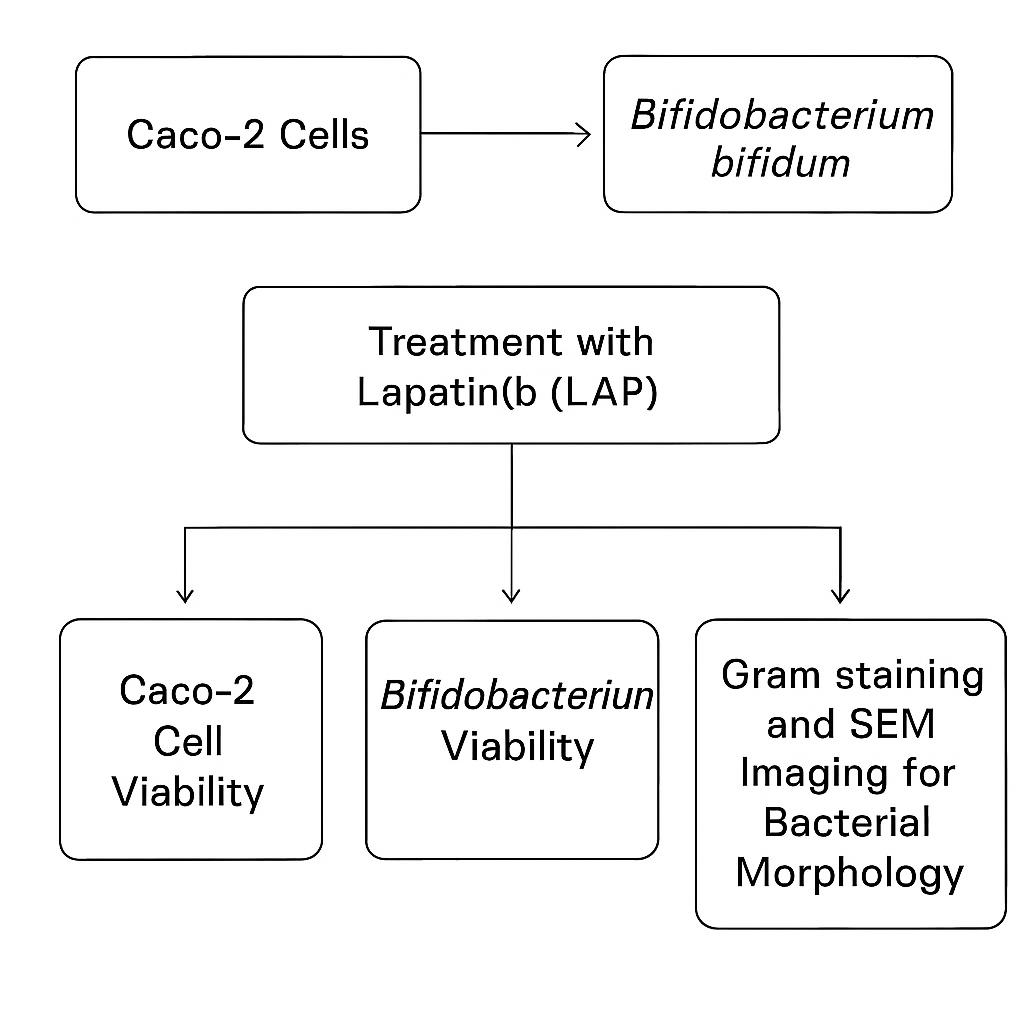

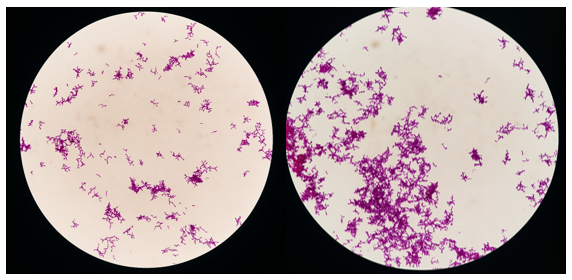

Methods: BB morphology was confirmed by Gram staining and scanning electron microscopy. Caco-2 cells, representing the intestinal epithelium, were co-cultured with BB at different bacterial concentrations and treated with LAP. Caco-2 cell viability was assessed using an MTS assay; BB viability was determined with a bacterial viability assay, while bacterial adhesion was quantified by recovering adhered BB following LAP treatment and enumerating colony-forming units (CFU).

Results: LAP reduced Caco-2 cell viability at all bacterial concentrations, although differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Although not statistically significant, a higher BB concentration (1 × 10^8 CFU/mL) was associated with slightly greater cell viability (86.60 % ± 2.73). While LAP initially decreased BB viability, bacterial proliferation subsequently increased, reaching 115.66 % ± 6.25 by 96 hours. A high number of viable, adhered BB was recovered from Caco-2 cells even after LAP treatment, indicating that bacterial-host interactions persisted despite drug exposure.

Conclusions: LAP suppresses epithelial cell viability and transiently reduces BB growth, but BB rapidly recovers and maintains adhesion to Caco-2 cells. LAP may induce epithelial stress that modifies surface properties, thereby favouring adhesion without preserving barrier integrity. Further studies assessing tight-junction proteins and permeability are needed to confirm whether BB adhesion mitigates LAP-induced epithelial disruption.

INTRODUCTION

Lapatinib (LAP) is an orally available small-molecule targeted agent that acts as a dual inhibitor of the ErbB1 and ErbB2 tyrosine kinases. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 37 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), among them tucatinib, gefitinib, and LAP, for the treatment of various malignancies 1. Nevertheless, the administration of these agents is associated with adverse events such as fatigue, cutaneous toxicity, cardiotoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity 2.

LAP exerts its antitumour activity primarily by inhibiting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/ErbB2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinases, which are critical regulators of tumour cell proliferation and survival. By competing with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) at the catalytic binding pocket, LAP disrupts downstream signalling through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT (PI3K/AKT), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, thereby arresting cell growth and/or inducing apoptosis 3. Despite its efficacy in HER2-positive breast cancer, LAP frequently causes gastrointestinal toxicity, most notably diarrhoea, which occurs in 58–78 % of recipients 4.

Emerging evidence indicates that the gut microbiome modulates gastrointestinal responses to anticancer therapies, including small-molecule TKIs and cytotoxic chemotherapy 5. In a preclinical model, LAP-treated rats exhibited a significant reduction in microbial diversity 6, and a clinical study documented diminished spp. in patients receiving TKIs 7. These observations suggest that LAP may inhibit the growth of in the small intestine, perturb gut homeostasis, and thereby contribute to diarrhoea. Nonetheless, the impact of LAP on the intestinal microbiota remains poorly defined.

Bifidobacteria (BB) are Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria that play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis owing to their immunomodulatory and antimicrobial properties. As some of the earliest microorganisms to colonise the human gastrointestinal tract, they confer health benefits comparable to those provided by Lactobacillus spp., which are commercially marketed as probiotics 6. Among probiotic bacteria, have been extensively studied for their favourable effects on the intestinal epithelial barrier; they can colonise the gut and adhere to epithelial cells throughout the gastrointestinal tract 7.

has been shown to reinforce intestinal tight junctions, suggesting potential therapeutic applications for the prevention or treatment of intestinal inflammation 8. Previous studies have demonstrated that BB can alleviate diarrhoea in animal models and are widely used to manage diarrhoea, constipation, and chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis, particularly with agents such as 5-fluorouracil 9. Consequently, investigating the relationship between and tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced diarrhoea may yield valuable insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Therefore, the present study aims to develop a co-culture model of Caco-2 cells and (BB) to investigate the effects of lapatinib (LAP) on intestinal epithelial cell viability, bacterial viability, and bacterial adhesion. was selected because of its role in maintaining gut homeostasis, reinforcing tight-junction integrity, and modulating inflammation. A reduction in abundance has been linked to gut dysbiosis, which may result in increased intestinal permeability and diarrhoea. Caco-2 cells, which differentiate into enterocyte-like monolayers, provide a reliable platform for studying intestinal epithelial responses to drug-induced toxicity and bacterial interactions. Using this model, we determined the optimal concentration for co-culture with Caco-2 cells and examined the impact of LAP on bacterial growth and adhesion. An adherence assay was performed to quantify BB attachment to Caco-2 cells, thereby simulating its natural interaction with the intestinal epithelium and assessing whether LAP disrupts bacterial–host interactions. The recovery of viable after LAP exposure was measured to ascertain whether BB adhesion to Caco-2 cells is compromised. Elucidating these interactions may provide insight into the pharmacological influence of LAP on the gut microbiota and inform strategies to manage LAP-induced diarrhoea.

METHODS

sample preparation

The reference bacterial strain (BB) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), United States. The strain was cultured on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (HiMedia, India) supplemented with 5 % sterile, expired human blood (Centre for Pathology Diagnostic & Research Laboratories, UiTM Private Specialist, Selangor, Malaysia). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C and anaerobically incubated for 96 h in an Oxoid AnaeroJar (2.5 L) containing Thermo Scientific Oxoid AnaeroGen gas-generating sachets. A Thermo Scientific anaerobic indicator strip was placed in each jar to verify oxygen depletion during incubation. The human blood employed was anonymised, expired clinical material that had not been collected specifically for research; consequently, institutional ethics approval was deemed unnecessary. A streak-plate technique was performed to isolate pure colonies from the primary culture. After confluent growth was observed, 50 % of the biomass was cryopreserved in cryovials at −80 °C, whereas the remaining colonies were suspended to a turbidity equivalent to the appropriate McFarland standard for subsequent experiments. Gram staining was performed to confirm strain identity because repeated subculturing can increase the risk of contamination. All procedures were conducted in a Class I biosafety cabinet under strict aseptic conditions and in accordance with the standard Gram-staining protocol. Slides were first examined with a compound microscope (Olympus CX31) at 40× magnification to assess staining characteristics: Gram-negative cells appear red-pink, whereas Gram-positive cells remain violet-blue. Subsequently, the preparations were inspected with a 100× oil-immersion objective to resolve cellular morphology and spatial distribution.

Caco-2 cell culture

The Caco-2 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Ham’s F-12 (Nacalai Tesque, Japan) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Tico Europe, Netherlands), 1 % antibiotic–antimycotic solution, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Nacalai Tesque, Japan). Cultures were grown in 25 cm flasks at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO. For subculturing, the spent medium was first aspirated and the monolayer briefly rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then detached with 1.5–2 mL of 0.01 % trypsin-EDTA in PBS and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C in 5 % CO.

After the cells had detached from the bottom surface of the flask, 10 mL of medium was added to terminate enzymatic digestion, and the suspension was divided equally between two flasks for subsequent treatments. Caco-2 assays were performed with passages 11–19. Each experiment comprised three technical replicates per condition. Cells were maintained under sterile conditions, and no evidence of bacterial or fungal contamination was detected throughout the culture period. Although mycoplasma testing was not available, cell health and morphology were carefully monitored up to passage 19.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), samples were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 2 mL of 4 % glutaraldehyde prepared in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Post-fixation was then carried out for 1 h at 4 °C in freshly prepared 1 % osmium tetroxide in the same buffer. The specimens were rinsed three times with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (10 min per wash, 4 °C) and subsequently dehydrated through a graded acetone series (30, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90 and 100 %) for 5 min at each step. After dehydration, samples were incubated sequentially in acetone:hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) mixtures (1:1 and 1:3, v/v) and finally in 100 % HMDS for 10 min each at room temperature. Following air-drying, the specimens were gently detached from the 24-well plate with sterile forceps, mounted on aluminium stubs, and sputter-coated with gold using an EMITECH K550X coater (Edwards, Czech Republic). Imaging was performed on a TM3030 Plus tabletop SEM (Hitachi, Japan) operated in high-vacuum mode with the manufacturer’s default parameters (accelerating voltage 15 kV; working distance and detector settings as recommended). Metadata, including magnification (×10 000) and scale bar (10 µm), were automatically embedded in the acquired micrographs.

Effect of LAP on Caco-2 cell viability at different co-culture concentrations using MTS cell proliferation assay

To examine the effect of (BB) on cell proliferation, Caco-2 cells (1 × 10 cells in 0.1 mL complete growth medium) were seeded into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate (Becton Dickinson, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO for 24 h to allow cell attachment. Each well was labeled according to the assigned treatment and prepared in triplicate. The next day, bacterial suspensions ranging from 10 to 10 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL were freshly prepared in 2 mL serum-free medium in sterile test tubes. The spent growth medium was removed from the plate, and the wells were replenished with the serially diluted bacterial suspensions. The plate was then incubated overnight to permit bacterial adhesion to the Caco-2 monolayer before subsequent LAP treatment on the following day.

A lapatinib (LAP) stock solution (17.2096 mM) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was freshly diluted in serum-free medium to a final concentration of 28 µM immediately before treatment. This concentration was chosen based on the study by Raja Sharin et al. 10, who reported a median IC of 28 µM for LAP in Caco-2 cells after 48–96 h of exposure and also observed concomitant barrier dysfunction. According to the Australian Public Assessment Report (AusPAR) 11 for lapatinib, steady-state plasma concentrations achieved after the approved 1 250 mg oral dose are approximately 2.43 µg/mL (~4.2 µM). However, limited oral bioavailability, food-dependent absorption, and substantial intestinal exposure indicate that luminal concentrations may exceed plasma levels. Consequently, 28 µM was selected as an exploratory concentration to model potential local intestinal effects and barrier impairment. An equivalent concentration of DMSO was prepared fresh and used as the vehicle control.

Following treatment with LAP and DMSO, the plates were incubated for an additional 96 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO. All manipulations were performed under aseptic conditions to contamination of both the culture medium and the laboratory environment. After the 96 h incubation, 10 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for a further 1 h prior to measurement of absorbance at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan, Switzerland). Untreated Caco-2 cells served as the negative control. The percentage of cell viability was calculated according to the following equation:

A graph of the percentage of Caco-2 cell viability versus the concentration of BB culture was plotted to identify the optimum concentration of BB culture that maintained both bacterial survival and a measurable Caco-2 cellular response. The optimum bacterial concentration determined from this experiment was then used for subsequent assays.

Effect of LAP on bacterial viability in Caco-2 cells at different incubation periods using bacterial viability assay

Caco-2 cells (1 × 10 cells in 0.1 mL complete growth medium) were seeded into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate (Becton Dickinson, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO for 24 h to allow cell attachment. The cells were seeded in four 96-well plates, each designated for a distinct incubation period (24 h, 48 h, 72 h, or 96 h). After 24 h of incubation, a bacterial suspension at the optimal concentration of 1 × 10 CFU mL, previously determined, was freshly prepared in a sterile test tube containing 2 mL of serum-free medium. The inoculum was adjusted according to the 0.5 McFarland standard (≈ 1 × 10 CFU mL), corresponding to an OD of 0.08–0.10. The spent growth medium in each well was discarded and replaced with the bacterial suspension to permit BB adhesion to the Caco-2 monolayer overnight prior to LAP treatment.

Following LAP treatment, plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO for 24, 48, 72, or 96 h to assess bacterial viability within Caco-2 cells. Based on the findings of Raja Sharin et al. 10, who reported that LAP inhibited Caco-2 cell growth by ≈ 50 % at 48, 72, and 96 h, the 96-h time-point was selected to evaluate the effects of LAP on both BB and Caco-2 cell proliferation. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) served as the vehicle control, and an additional control containing BB alone was included to monitor bacterial growth over time. All manipulations were performed under aseptic conditions to contamination. Bacterial viability was quantified by measuring optical density at 596 nm with a microplate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan, Switzerland); the percentage viability was then calculated using the following equation:

Bacterial adherence assay of culture growth in Caco-2 cells

The adhesion assay for BB strains on Caco-2 cells was performed according to the method described by Gagnon et al. 12, with minor modifications. Caco-2 cells (1 × 10 cells in 0.1 mL of complete growth medium) were seeded into a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, BB suspensions (0.52–0.56 nm) prepared in Modified Reinforced Clostridial Broth (ATCC medium 2107; HiMedia, India) were added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 1000:1 (1 × 10 CFU/mL BB to 1 × 10 Caco-2 cells). BB cultures were harvested at the mid-log phase (OD ≈ 0.08–0.10), corresponding to a McFarland 0.5 standard. The co-cultures were then maintained in antibiotic-free, serum-free medium for an additional 24 h to prevent bacterial suppression.

Following co-culture with BB, cells were treated with LAP (28 µM) and incubated for 96 h. Subsequently, non-adherent bacteria were removed by gently washing with sterile PBS, whereas adherent bacteria were released by incubating the cells with 100 µL trypsin per well for 5 min at 37 °C. The cell suspension was then serially diluted ten-fold (10–10 CFU/mL) in modified Reinforced Clostridial Broth. Aliquots were plated on Brain Heart Infusion Agar (HiMedia, India) supplemented with 5 % expired human blood (Centre for Pathology Diagnostic & Research Laboratories, UiTM Private Specialist, Sungai Buloh). Plates were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 96 h in an Oxoid AnaeroJar (2.5 L) with Thermo Scientific Oxoid AnaeroGen sachets; an anaerobic indicator strip confirmed oxygen depletion. Colony-forming units (CFU/mL) were enumerated according to the formula:

Bacterial adhesion was expressed as the percentage of adherent bacteria relative to the total bacterial count of the experiment. Typically, an acceptable range for accurate colony counting is between 25–250 or 30–300 colonies per agar plate (for a 100 mL sample) 13. Plates with colonies exceeding this range, labelled as “too numerous to count” (TNTC), are considered to be beyond the quantifiable detection limit.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, USA). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) from three technical and biological replicates. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Given the exploratory nature of this study, formal correction for multiple comparisons was not applied; all p-values are reported for transparency, and trends with p > 0.05 are interpreted descriptively. An increased sample size will be used in future experiments to enhance statistical robustness and confirm the reproducibility of observed trends.

RESULTS

Gram staining of

The Gram staining technique was employed to differentiate bacterial isolates on the basis of cell-wall thickness and permeability, thereby classifying them as either Gram-positive or Gram-negative. As shown in Figure 1, the isolate exhibits a rod-shaped morphology with irregularly distributed bifid branches and is stained purple to purplish-pink. These features are consistent with the description provided by Cunningham et al. 14, who reported that spp. are non-motile, Gram-positive, non-spore-forming organisms that are predominantly rod-, curved-, or club-shaped and frequently display Y- or V-shaped branching.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is widely used in microbiological analyses to examine bacterial cell morphology, surface adhesion, and biofilm formation 15. This technique enables detailed evaluation of the morphology and distribution of BB on the examined surface. The findings shown in Figure 2 are consistent with those of Zhang et al. 16, who observed bifidobacteria with rod-shaped, bifurcated morphologies arranged randomly. Most bifidobacterial strains exhibited a smooth surface, whereas a minority displayed a wrinkled texture.

Scanning electron micrograph showing a pleomorphic rod-shape containing

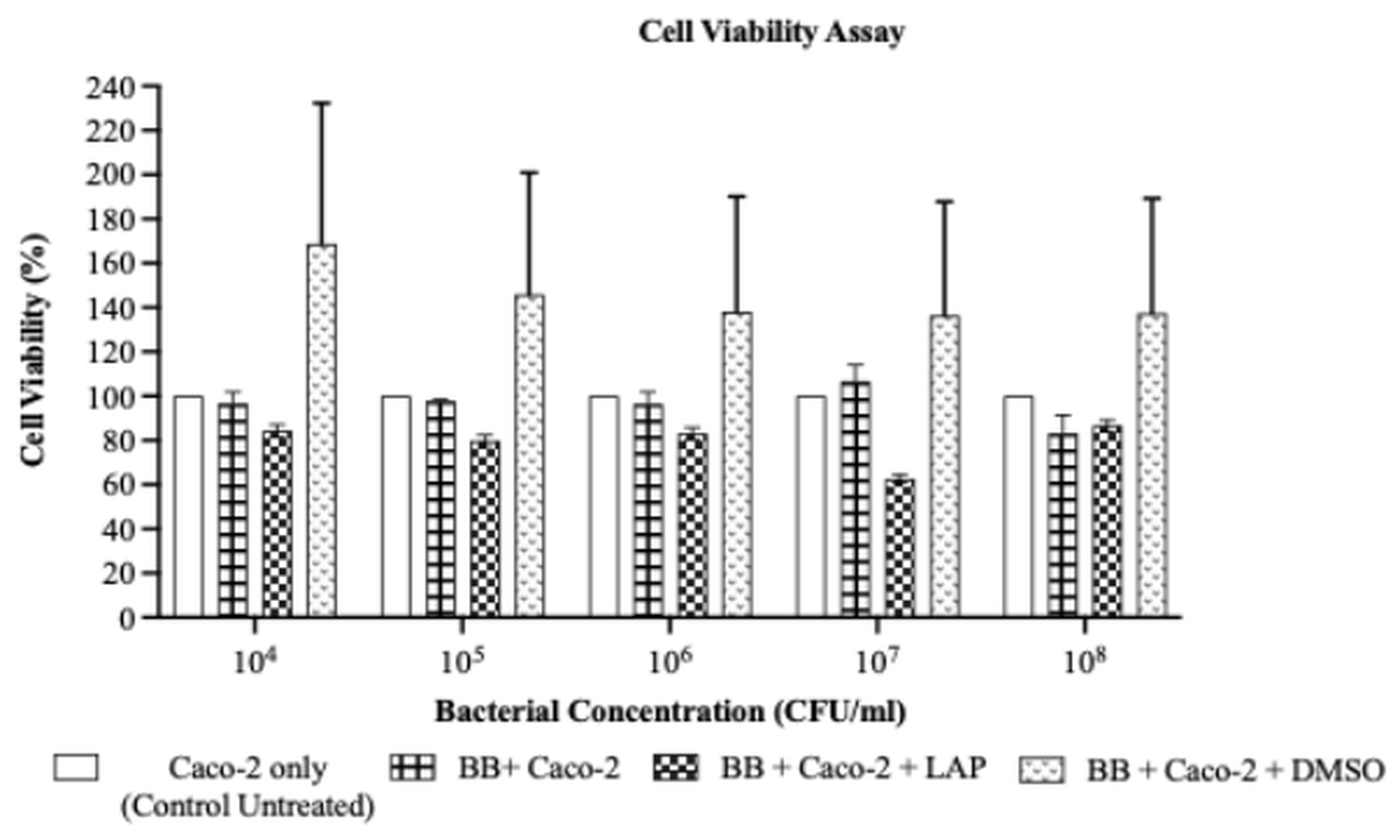

Effect of LAP on Caco-2 cells co-cultured with different concentration of

The impact of LAP on the viability of Caco-2 cells co-cultured with BB was evaluated by the MTS assay after 96 h. As illustrated in Figure 3, LAP reduced Caco-2 viability at all tested BB inocula relative to the untreated BB–Caco-2 co-culture (BB + Caco-2); however, no significant inter-group differences were detected (p > 0.05). Specifically, Caco-2 viability was 84.35 ± 2.66 % at 1 × 10 CFU/mL, 79.87 ± 2.52 % at 1 × 10 CFU/mL, 83.12 ± 2.62 % at 1 × 10 CFU/mL, and 62.68 ± 1.98 % at 1 × 10⁷ CFU/mL. Although the difference was not significant, viability increased to 86.60 ± 2.73 % at 1 × 10 CFU/mL, suggesting a modest positive correlation between BB density and Caco-2 viability. Because the inhibitory effect of LAP did not differ significantly across the inocula, 1 × 10 CFU/mL was chosen as the optimal BB concentration for subsequent assays, providing a stable bacterial load and a discernible response in the Caco-2 co-culture.

Percentage of Caco-2 cell viability following lapatinib (LAP) treatment after 96 hours at different BB bacterial concentrations. LAP exhibited inhibitory effect on Caco-2 cells, with decreasing cell viability with an increase of BB concentrations from 1 × 104 CFU/mL to 1 × 107 CFU/mL (84.35% ± 2.66 at 1 × 104 CFU/mL, 79.87% ± 2.52 at 1 × 105 CFU/mL, 83.12% ± 2.62 at 1× 106 CFU/mL, 62.68% ± 1.98 at 1 × 107 CFU/mL). Percentage of cell viability increased (86.60% 2.73) at 1 × 108 CFU/mL. However, no significant difference was observed between all bacterial concentrations (p = 0.9326). Data were expressed as mean ± S.E.M,

Effect of LAP on in Caco-2 cells at different incubation periods

Figure 4 presents a bar chart of the bacterial viability assay, in which Caco-2 cells were exposed to a fixed bacterial concentration of 1 × 10 CFU/mL. Subsequently, the Caco-2/BB co-cultures were treated with LAP for 24, 48, 72, or 96 h. This experimental design simulates the intestinal milieu and aims to identify the optimal incubation period for BB proliferation within Caco-2 cells, thereby elucidating bacterial viability and host–cell interactions under LAP exposure.

The bacterial viability assay was performed to assess the viability of BB following lapatinib (LAP) treatment at different incubation periods (24, 48, 72, and 96 hours). Caco-2 cells were incubated with a fixed bacterial concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL and subsequently treated with LAP, while DMSO was used as vehicle control in this experiment. Bacterial viability was measured at 596 nm using a spectrophotometer. The results indicate that BB viability gradually increased over time following LAP treatment, with 44.10% ± 6.82 viability observed at 24 hours (p = 0.0442 vs control), 68.80% ± 14.54 at 48 hours (p = 0.4360), 97.88% ± 3.88 at 72 hours (p = 0.9725), and 115.66% ± 6.25 at 96 hours (p = 0.3536). Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M (n = 3) and statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 considered significant.

After 96 h of treatment, the bacterial viability assay demonstrated that LAP significantly modulated BB growth. As illustrated in Figure 4, the untreated control (BB) exhibited baseline growth (100 %). Co-culture with Caco-2 cells (BB + Caco-2) enhanced bacterial viability to 125.82 % ± 4.80, confirming proliferation in the presence of intestinal epithelial cells. Conversely, supplementation with LAP (BB + LAP) reduced bacterial viability to 84.61 % ± 1.69, indicating an inhibitory effect. Notably, simultaneous exposure of the co-culture to LAP (BB + Caco-2 + LAP) maintained bacterial viability at 115.66 % ± 6.25. Collectively, these data indicate that BB at 1 × 10 CFU mL remains viable and does not significantly compromise Caco-2 proliferation under LAP treatment (p > 0.05). Because the viability assay alone cannot ascertain Caco-2 cell growth, a subsequent bacterial adherence assay was undertaken to evaluate epithelial cell viability and proliferation more directly.

Effect of LAP on -Caco-2 cell adhesion

The adherence assay provided additional evidence that Caco-2 cells remain viable in the presence of BB, thereby corroborating that a bacterial load of 1 × 10 CFU/mL sustains both bacterial viability and host-cell integrity under these experimental conditions. The adherence of BB to Caco-2 cells was assessed after LAP treatment. In parallel, Caco-2 monolayers exposed to LAP alone (i.e., without BB) were examined to verify the absence of microbial contamination and to evaluate the direct effects of LAP on the epithelial cells; because no bacterial binding occurred in this control, the corresponding data were excluded from the adherence analysis. Serial dilutions ranging from 10 to 10 CFU/mL were inoculated onto selective agar by the streak-plate method. Resultant colonies appeared milky-white with smooth margins; Gram staining confirmed the morphology characteristic of BB as previously described. After 72 h of incubation, colonies grown on all 48 agar plates were harvested, colony-forming units were enumerated to quantify bacterial adherence, and the results were expressed as CFU/mL.

Number of bacterial colonies at different dilution factors on agar plates after 72 hours of incubation using the bacterial adherence assay. The colony count increased as the dilution factor decreased, with a noticeable increase at the 1 × 107 dilution. At 1 × 106 dilution, significant differences were observed between LAP-treated group and BB Control Untreated (p = 0.0458). At the highest dilution (1 × 108) all three groups—BB Control Untreated, BB + Caco-2, and BB + Caco-2 + LAP–exceeded the countable range (>300 colonies) and were therefore excluded from CFU conversion. Data were presented as mean ± S.E.M (

As shown in Figure 5, bacterial adherence increases progressively with each successive inoculum dilution; however, a significant inhibition is evident at the 1 × 10 dilution in the LAP-treated group relative to the untreated BB control and the BB-infected Caco-2 cells. The 1 × 10⁷ dilution yielded the highest colony count among all groups, indicating that LAP does not suppress bacterial proliferation. At the highest dilution (1 × 10), all three groups—BB Control Untreated, BB + Caco-2, and BB + Caco-2 + LAP—exceeded the upper countable limit (>300 colonies); therefore, these plates were excluded from CFU calculations, and adhesion was expressed solely as the percentage of adherent bacteria relative to the initial inoculum. Taken together, these findings indicate that LAP treatment does not substantially inhibit BB growth at higher dilution factors.

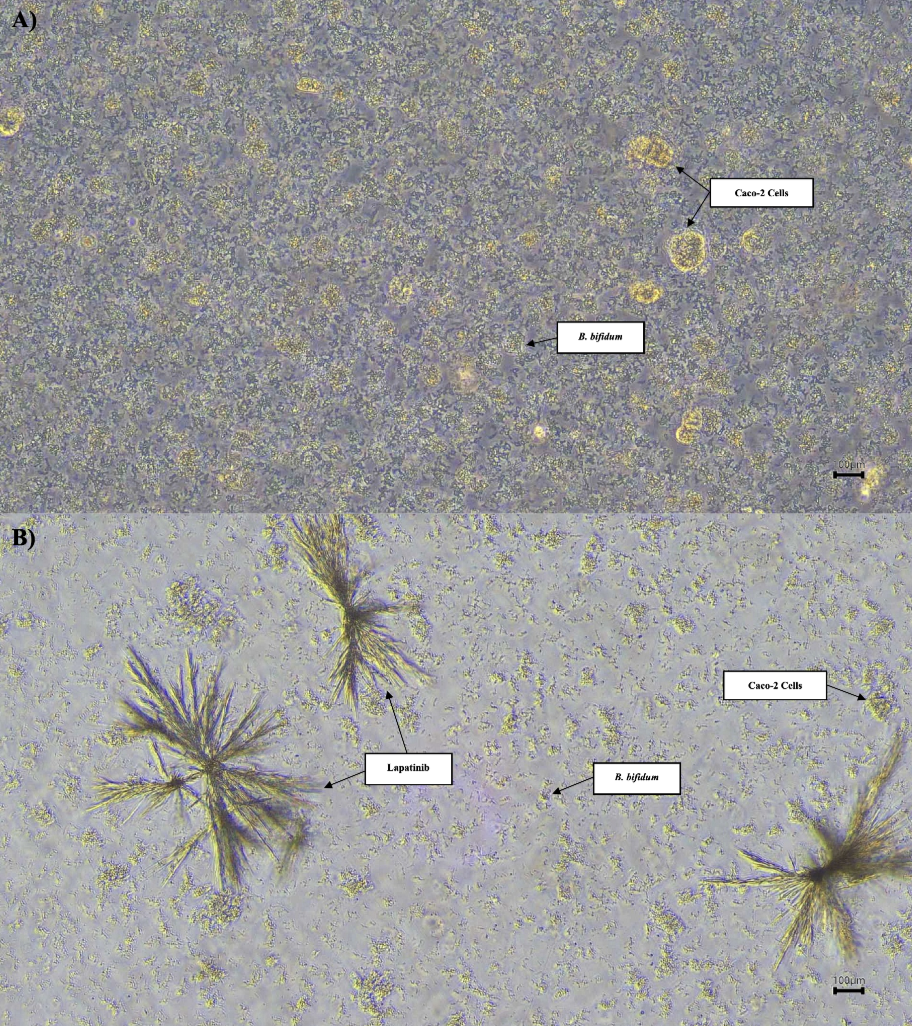

Phase contrast micrographs of Caco-2 cells co-cultured with BB at 20× objective magnification. A) Caco-2 cells co-cultured with BB showed normal growth prior to LAP treatment. B) After 96 hours of incubation with LAP, a noticeable reduction in both Caco-2 cells density and BB presence was observed, indicating LAP’s inhibitory effect on cellular and bacterial proliferation. Scale: 100 μm.

Figure 6 illustrates the differences in the growth of Caco-2 cells and BB before and after treatment with LAP. After 24 h of incubation without LAP, both Caco-2 cells and BB exhibited normal proliferation patterns. In contrast, after 96 h of incubation in the presence of LAP, a pronounced reduction in the growth of both Caco-2 cells and BB was observed. Nevertheless, the colony-forming unit (CFU) count on the plate for the BB + Caco-2 + LAP group remained the highest, suggesting that bacterial–host interactions persist despite LAP exposure.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the effects of LAP on the adhesion and viability of (BB) in a Caco-2 cell culture model, as well as its potential role in LAP-induced epithelial disruption. Gram staining and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were performed to characterise the morphology of BB. Gram staining confirmed that the bacteria were rod-shaped, bifid organisms that retained the crystal violet stain. SEM analysis corroborated these observations, showing a bifurcated, randomly arranged morphology, as described by Zhang et al. 16. Gram staining was repeated after the bacterial adhesion assay to reconfirm morphology, demonstrating that BB maintained its structure even after LAP treatment.

Caco-2 cell and bacterial viability assays were performed to evaluate the effects of LAP on Caco-2 cell viability and BB growth. The MTS assay revealed that LAP significantly inhibited Caco-2 cell proliferation at all bacterial concentrations tested. However, the inhibitory effect declined as the bacterial concentration increased, suggesting a dose-dependent reduction in LAP cytotoxicity at higher bacterial densities. Conversely, although LAP initially suppressed BB viability, bacterial growth rebounded over time—from 44.10 % viability at 24 h to 115.66 % at 96 h. This observation indicates that BB can survive and proliferate despite LAP exposure, which is consistent with previous reports that beneficial gut bacteria adapt to certain stressors 17. Bacterial viability was monitored by optical density at 596 nm, serving as an approximate indicator of growth; nevertheless, this method may be confounded by host-cell debris and bacterial aggregation in mixed cell–bacteria suspensions. Accordingly, more precise quantification methods, such as serial plating at each time point or RT-qPCR, should be employed in future studies. Furthermore, complementary barrier-integrity assessments—including TEER, FITC-dextran flux, and tight-junction protein analysis—are recommended to verify the functional impact of BB under LAP exposure.

To determine the optimal BB concentration for co-culture, a concentration of 1 × 10 CFU/mL was selected because it balances bacterial viability with host-cell responses. This concentration is consistent with previous studies indicating that BB at this level supports intestinal health, rendering it suitable for subsequent experiments 18. Al-Sadi et al. 19 reported that BB at 1 × 10 CFU/mL maximally enhanced the intestinal epithelial tight-junction barrier in Caco-2 monolayers, highlighting its therapeutic potential for modulating intestinal barrier function.

A study by Leech et al. 20 demonstrated reduced expression of the junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A), a tight junction protein, in LAP-treated cells. This finding indicates that LAP increases intestinal permeability by disrupting tight-junction architecture, thereby promoting inflammation, compromising barrier integrity, and ultimately precipitating diarrhoea 21. Although LAP exposure in the presence of BB marginally increased Caco-2 cell viability at 1 × 10 CFU/mL, the difference was not statistically significant. One plausible explanation is that BB modulates the intestinal milieu via metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs); however, this hypothesis remains unverified and necessitates direct metabolomic assessment. In support of this concept, Hsieh et al. 22 reported that enhanced production of SCFAs—particularly acetate and formate—restores epithelial tight-junction function. Collectively, these data suggest that BB may reinforce barrier integrity through SCFA-mediated mechanisms, but this contention requires further validation.

The adherence assay employed in this study adheres to conventional protocols, permitting bacterial attachment to host cells, followed by washing and enumeration of viable adherent bacteria via colony-forming unit (CFU) determination 23. Although CFU quantification remains the reference method, it is labor-intensive and susceptible to errors caused by bacterial clumping, which may yield inaccurate adherence estimations. Emerging approaches, including bioluminescence-based assays, may improve both the precision and throughput of adherence measurements 24. Future investigations should therefore incorporate these alternative techniques to achieve a more comprehensive assessment of bacterial adherence in the presence of LAP.

The ability of BB to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells in the human gut is critical for maintaining gut microbiota stability 25. In the present study, LAP treatment significantly decreased bacterial adhesion to Caco-2 cells. However, BB continued to proliferate following exposure to LAP. The bacterial adherence assay demonstrated that LAP modifies BB attachment to Caco-2 cells. The persistently elevated CFU/mL values across all dilution factors indicate that BB remained viable and adhered to Caco-2 cells despite LAP exposure (Figure 5). Although LAP transiently impaired bacterial viability, BB subsequently recovered and multiplied, confirming that bacterium–host interactions were preserved. Notably, the high bacterial counts on agar plates suggest that LAP does not inhibit BB growth but rather alters its interaction with the intestinal epithelium. After trypsinisation and removal of the culture medium, the remaining bacteria likely represented those still attached to the Caco-2 monolayer. Accordingly, the elevated CFU/mL values imply that bacterial adhesion was largely maintained despite LAP treatment, supporting the persistence of bacterial–host interactions.

Further analyses (Figure 6) demonstrated decreased Caco-2 cell viability, confirming the cytotoxic effect of LAP on intestinal epithelial cells. Nevertheless, the persistence of viable, adherent BB following LAP exposure indicates that bacterial colonisation was not completely abrogated. While the data indicate a potential protective effect, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). Consequently, these results should be regarded as preliminary, and larger-scale investigations are warranted to corroborate the observations. The present study employed a single ATCC reference strain for proof-of-concept purposes; however, strain-dependent variability in adhesion and host interaction is well-documented. Future work will therefore include additional clinical isolates to capture this heterogeneity and enhance translational relevance.

This observation concurs with the findings of Raja Sharin et al. 26, who reported that LAP enhances permeability of Caco-2 intestinal monolayers and down-regulates tight-junction proteins via ErbB1 inhibition. In the present study, robust bacterial–host interactions persisted after LAP exposure, as indicated by persistently elevated colony counts. These results imply that, while bacterial adhesion of BB was retained, LAP may have modulated the affinity and spatial distribution of bacterial attachment without fully abrogating bacterial–host interactions. By interfering with cell-signalling pathways or receptor expression, LAP could alter the canonical adhesion mechanism, thereby influencing BB–epithelial crosstalk. Consistent with previous reports, a significant decline in Caco-2 cell viability was observed after treatment, which aligns with previous findings that LAP compromises epithelial integrity. Nevertheless, the recovery of viable, adherent BB demonstrates that bacterial colonisation was not entirely abolished. Given that bacterial adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells is pivotal for maintaining gut microbiota homeostasis and intestinal barrier function 27, additional investigations are warranted to elucidate whether LAP-mediated changes in bacterial adhesion correlate with tight-junction disruption and heightened gut permeability.

Although this study did not perform direct assessments of barrier integrity, such as transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements or quantification of tight-junction protein expression, these analyses will be incorporated into future experiments to provide more robust evidence for changes in epithelial permeability. Collectively, the present findings advance our understanding of the potential impact of lapatinib (LAP) on host–microbiota interactions, which may underlie gastrointestinal adverse events, including diarrhoea. Whereas previous investigations have examined tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)–microbiota interactions more broadly, the current study offers an incremental contribution by analysing (BB) as a representative commensal species under lapatinib exposure. This targeted approach delivers proof-of-concept data that will guide subsequent, more comprehensive studies.

At a dilution of 10⁻⁷, the bacterial suspension still yielded > 3 × 10¹⁰ CFU·mL, rendering accurate colony counting impracticable because of confluent growth, even though this was not the most concentrated sample (10⁻). These findings corroborate the bacterial-viability assays, indicating that BB survives and proliferates in the presence of LAP. The elevated counts also imply that a fraction of the population may remain non-adherent or only loosely associated with Caco-2 monolayers. Clinically, such overgrowth, together with LAP-induced epithelial compromise, could potentiate diarrhoeal manifestations in treated patients 28. Additional studies are therefore warranted to clarify whether LAP-mediated alterations in bacterial adhesion drive gut dysbiosis and increase intestinal permeability.

This study has several limitations. The lapatinib concentration employed (28 µM) represents an exploratory dose that surpasses typical clinical plasma levels; however, it was selected on the basis of prior optimization in Caco-2 cells to ensure reproducible effects. Direct barrier-integrity measurements, such as transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), FITC-dextran permeability, and tight-junction protein expression, were not performed; therefore, any conclusions regarding epithelial permeability should be considered exploratory. Moreover, only a single ATCC strain was tested, and although anaerobic jars were used to reduce oxygen tension, the co-culture environment may not fully replicate the strictly anaerobic conditions of the human intestine. Future studies will apply clinically relevant lapatinib concentrations to more accurately reflect pharmacokinetics, incorporate comprehensive barrier-function assays, and evaluate additional clinical isolates to enhance the mechanistic and translational relevance of this model.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings do not demonstrate functional mitigation of LAP-induced epithelial barrier dysfunction by BB; instead, they indicate that BB remains viable and adherent during LAP exposure. The persistence of BB should not be construed as evidence of epithelial protection, particularly in the absence of direct assessments of barrier integrity. Further mechanistic investigations—encompassing tight-junction protein expression, TEER measurements, permeability assays, and models—are necessary to ascertain whether BB persistence is physiologically relevant. Currently, the data do not support any therapeutic application; rather, they position BB as a pertinent model organism for examining drug–microbiota interactions under TKI exposure.

ABBREVIATIONS

3D: Three-Dimensional; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; AusPAR: Australian Public Assessment Report; BB:; BHI: Brain Heart Infusion; Caco-2: Human Colon Adenocarcinoma; CFU: Colony-Forming Unit; DMSO: Dimethyl Sulfoxide; EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid; EGFR: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; ErbB: Erythroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogene Homolog; FBS: Fetal Bovine Serum; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; FITC: Fluorescein Isothiocyanate; GI: Gastrointestinal; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2; HMDS: Hexamethyldisilazane; JAM-A: Junctional Adhesion Molecule A; LAP: Lapatinib; MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; MOI: Multiplicity of Infection; mTOR: Mammalian Target of Rapamycin; MTS: 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-Carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-Sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium; OD: Optical Density; PBS: Phosphate-Buffered Saline; PI3K/AKT: Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B; rEGF: Recombinant Epidermal Growth Factor; RT-qPCR: Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction; SCFA: Short-Chain Fatty Acid; SEM: Scanning Electron Microscopy; TEER: Transepithelial Electrical Resistance; TJP: Tight Junction Protein; TKI: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor; TNTC: Too Numerous To Count.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Institute of Medical and Molecular Biotechnology (IMMB), Faculty of Medicine, and Faculty of Dentistry, Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) for providing the research facilities.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

NSH, WNIWMZ, and NANR performed the research, drafted the manuscript, addressed reviewer comments, and revised the references to the required citation style. NAHH and HAT contributed by critically reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine, UiTM, for the Faculty of Medicine Research Grant funding (FMRG): 600-TNCPI 5/3/DDF (MEDIC) (009/2021).

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Expired human blood used in BHI agar was obtained from UiTM Private Specialist Centre, Selangor, Malaysia. The material was anonymised and not collected specifically for research purposes; therefore, ethics approval was not required.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.