Insights into microbiome-based therapeutics: Engineered probiotics, bacteriophages, and microbiome-derived metabolites

- Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Al-Asmarya Islamic University, Zliten, Libya

- Libya Centre for Sustainable Development (KSD) Zliten, Libya

- Department of zoology, Faculty of science, Sabratha University, Sabratha, Libya

- Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Health Sciences, Misurata University, Misurata, Libya

- Department of botany, Faculty of Science, Al-Asmarya Islamic University, Zliten, Libya

Abstract

The human microbiome is increasingly recognized as a key regulator of immunity, metabolism, and disease progression; however, conventional interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation remain limited by their precision and yield inconsistent outcomes. Recent advances in biotechnology have catalyzed the development of engineered probiotics, bacteriophage therapy, and microbiome-derived metabolites as next-generation therapeutics. Engineered probiotics can now be reprogrammed via synthetic biology to sense disease states, secrete therapeutic molecules, and modulate host responses. Bacteriophages, including engineered variants, provide highly selective antibacterial activity and may help address antimicrobial resistance. Microbial metabolites—including short-chain fatty acids and bile-acid derivatives—function as systemic modulators and constitute emerging drug candidates. This review critically examines these three modalities, emphasizing both their individual advances and their potential for synergistic integration into multimodal, precision-tailored therapies. We further highlight translational challenges, including biosafety concerns, inter-individual microbiome variability, manufacturing scalability, and unresolved regulatory issues, and outline future directions that could transform the microbiome from a disease biomarker into a therapeutic frontier for precision medicine.

Introduction

The human microbiome has emerged as a pivotal determinant of health and disease, shaping immune responses, metabolic pathways, and neurological functions through a dynamic interplay between host and microbial communities 1. With advances in next-generation sequencing and multi-omics technologies, the microbiome is now recognized not merely as a passive collection of microbes but as a complex, organ-like system that exerts systemic effects. Dysbiosis, defined as a disruption in microbial composition or function, has been implicated in a broad spectrum of diseases, ranging from inflammatory bowel disorders and metabolic syndrome to cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and autoimmune conditions 2,3. This growing recognition has accelerated efforts to translate microbiome science into tangible biomedical interventions. Conventional strategies, such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), have laid the foundation for microbiome-based therapeutics 4. However, these approaches are often limited by their lack of precision, inconsistent efficacy across individuals, and difficulties in establishing long-term colonization 5. Similarly, broad-spectrum antibiotics, while effective against pathogens, disrupt the commensal microbial balance and contribute to the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance 6,7. Consequently, there is a pressing need for next-generation strategies that can selectively modulate microbial communities, enhance therapeutic precision, and minimize unintended consequences. Engineered probiotics, enabled by synthetic biology, have been designed to sense disease biomarkers, produce therapeutic molecules, and modulate immune responses with unprecedented specificity 8. Bacteriophages, the natural predators of bacteria, are being re-engineered to selectively eliminate pathogenic strains while preserving commensals, offering solutions to multidrug resistance and targeted microbiome modulation 9. Meanwhile, microbiome-derived metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, bile-acid derivatives, and tryptophan metabolites, are increasingly recognized as bioactive molecules that regulate systemic processes, from gut–brain communication to metabolic homeostasis. Harnessing these metabolites, or developing synthetic analogues, represents a new therapeutic frontier 10. While individual reviews have addressed probiotics, phages, or metabolites in isolation, few have integrated these domains into a cohesive framework. The novelty of this review lies in its comprehensive synthesis of three interconnected therapeutic strategies—engineered probiotics, bacteriophages, and microbiome-derived metabolites—as components of a unified microbiome-based therapeutic paradigm. This integrative perspective is essential, as emerging evidence suggests that the most effective microbiome interventions will combine multiple modalities, supported by precision-medicine tools such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and artificial-intelligence-driven modeling of host–microbiome interactions. The importance of this study extends beyond academic exploration. Microbiome-based therapeutics hold transformative potential for addressing some of the most urgent biomedical challenges: combating antimicrobial resistance, improving cancer immunotherapy outcomes, managing metabolic and autoimmune diseases, and enabling personalized medicine. By critically evaluating current advances, limitations, and translational barriers, this review aims to provide a strategic roadmap for the development of next-generation microbiome therapeutics. In doing so, it highlights both the scientific novelty and the clinical urgency of integrating engineered probiotics, bacteriophages, and microbial metabolites into future biomedical practice.

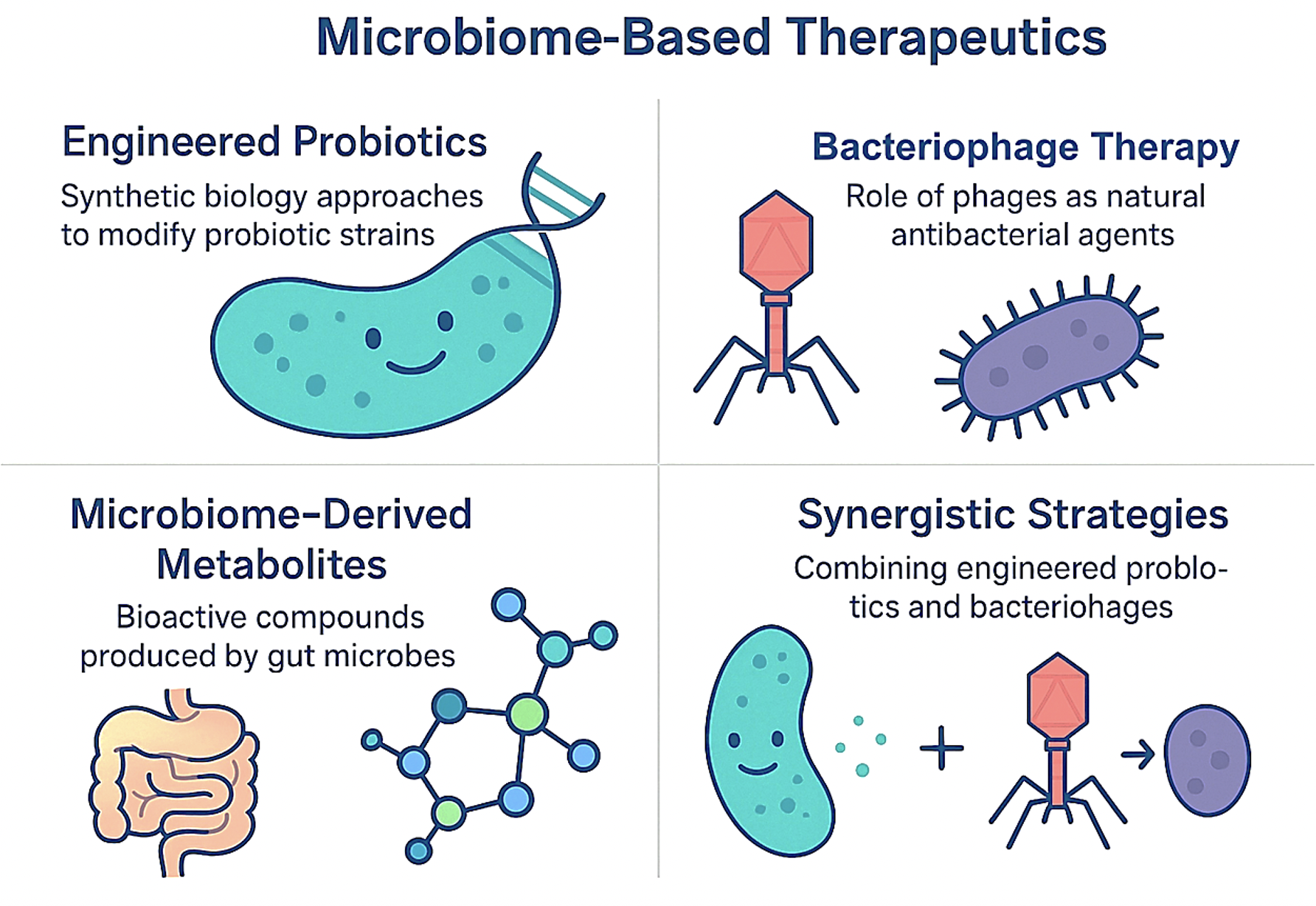

Engineered Probiotics: Synthetic biology approaches to modify probiotic strains

The advent of synthetic biology has transformed probiotics from empirical dietary supplements into programmable biological devices capable of performing highly specific therapeutic functions. Genetically engineered and chemically modified probiotic strains have been developed for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease 11. For example, the well-characterised probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (ECN) has been engineered to secrete low doses of interleukin-2 (IL-2), selectively expanding regulatory T cells (Tregs) and thereby restoring immune tolerance. To improve viability and targeted delivery, the engineered strain (ECN-IL2) is encapsulated in Eudragit L100-55, which dissolves in the intestinal pH and facilitates site-specific release. Conventional probiotics, although widely marketed for gastrointestinal and immunological health, have been criticised for limited reproducibility, transient colonisation, and poorly defined mechanisms of action 12. These limitations highlight the need to progress beyond ‘naturally occurring’ strains toward rationally engineered probiotics that can be precisely matched to defined disease contexts. Figure 1 summarises how synthetic biology can convert conventional probiotics into programmable therapeutic agents. By integrating synthetic genetic circuits, engineered probiotics can acquire novel capabilities such as targeted drug delivery, prolonged gut persistence, and pathogen-responsive activity, positioning them as promising platforms for microbiome-based therapeutics.

Schematic overview of synthetic biology approaches for engineering probiotics. Conventional probiotics are reprogrammed using synthetic genetic circuits to acquire advanced therapeutic functions. These include the ability to sense disease-specific biomarkers (e.g., inflammation), produce and deliver therapeutic molecules (e.g., cytokines, antimicrobial peptides) on demand, and exhibit improved gut colonization and persistence. This transformation positions engineered probiotics as programmable, precision platforms for next-generation microbiome-based therapies.

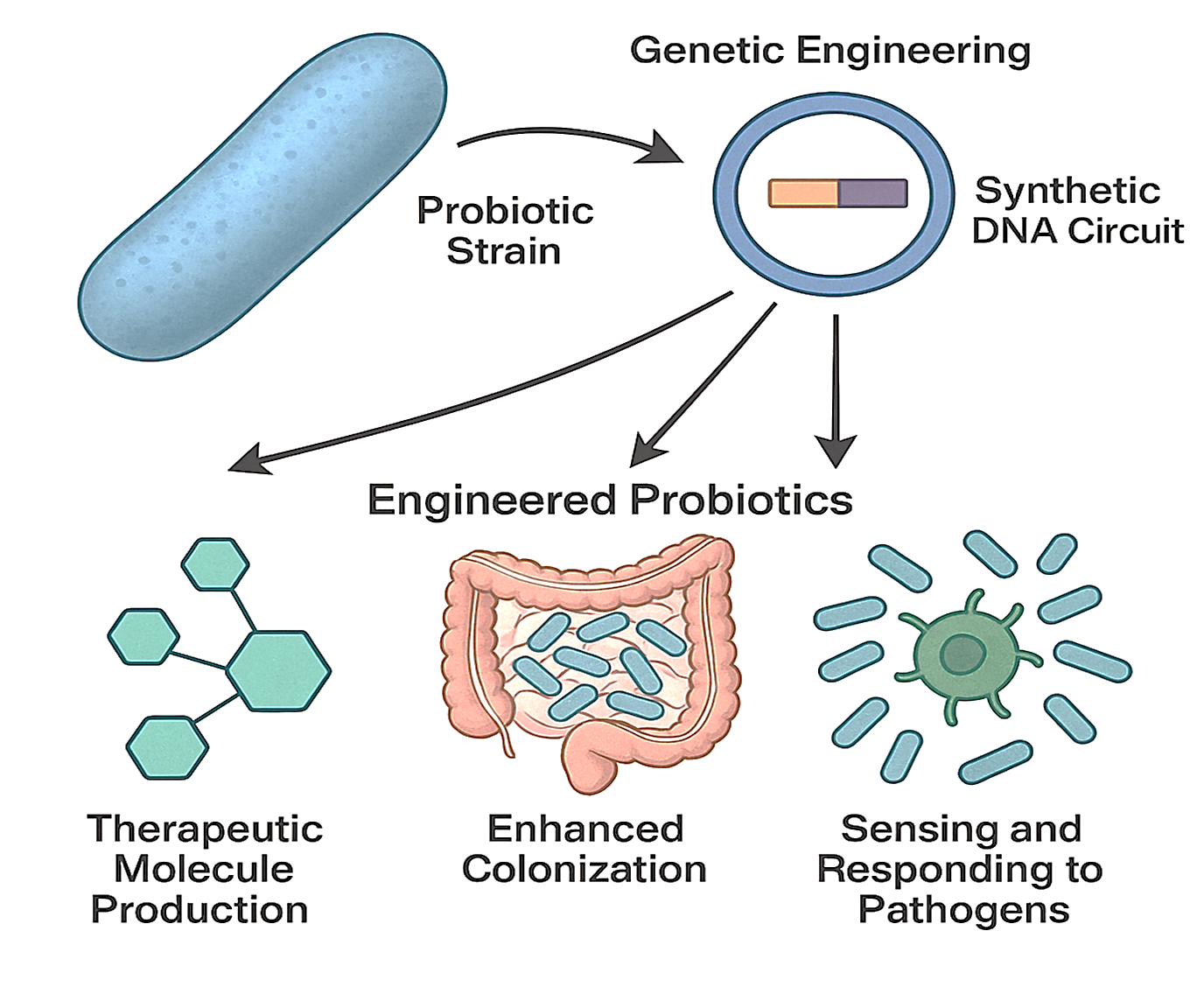

The engineering of probiotics has been propelled by advancements in genetic circuit design, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)–Cas editing platforms, and modular plasmid systems 8. Unlike traditional mutagenesis or random strain selection, these approaches enable predictable, scalable, and precisely targeted modifications. For instance, logic-based gene circuits allow engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 to detect inflammatory biomarkers and, only under pathophysiological conditions, secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines, thereby minimizing off-target effects 13. Similarly, metabolic rewiring of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains facilitates controlled production of antimicrobial peptides or small-molecule therapeutics 14. A recent study highlighted the transformative potential of the CRISPR/Cas system as a precise gene-editing tool for modulating gut microbes, offering new avenues for functional screening and therapeutic intervention 15. This approach underscores the promise of microbiota-targeted genome editing in managing metabolic disorders and advancing personalized medicine. Nonetheless, several critical challenges remain. Engineered functions often impose metabolic burdens on the host strain, leading to reduced fitness and instability during long-term colonization 16. Moreover, although most constructs perform robustly in vitro, their behavior within the complex and competitive gut ecosystem is less predictable. This highlights the need for systems-level modeling and in vivo validation prior to clinical translation. Figure 2 summarizes contemporary approaches to microbiome-based therapeutics and delineates the limitations of both traditional and next-generation interventions 17.

Landscape of microbiome-based therapeutic strategies. This diagram compares traditional interventions, such as probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), with next-generation approaches, including engineered microbes. The illustration highlights how these diverse strategies aim to restore microbial balance, alleviate dysbiosis, and enable targeted, site-specific interventions. Adapted with permission from

Engineered probiotics are no longer confined to gastrointestinal health; they are increasingly envisioned as living therapeutics across diverse biomedical fields 8. In metabolic disorders such as phenylketonuria and diabetes, probiotic strains have been programmed to catabolize toxic metabolites or modulate glucose levels, offering alternatives to enzyme-replacement therapies 18. In oncology, tumor-homing bacteria such as Salmonella and Clostridium have been engineered to deliver checkpoint inhibitors or pro-drug-converting enzymes directly into the tumor micro-environment, thereby reducing systemic toxicity compared with conventional chemotherapy 19. Importantly, these applications represent a paradigm shift from passive commensals to active therapeutic agents. However, most of these demonstrations remain pre-clinical or confined to early-phase trials 19,20. While results are promising, the translation gap stems from unresolved questions regarding strain stability, dosing consistency, and inter-individual microbiome variability, which collectively influence therapeutic outcomes 21. Perhaps the most formidable barrier to clinical adoption is biosafety 22. Engineered probiotics are live organisms, and their administration to human hosts raises concerns about horizontal gene transfer, unintended ecological disruptions, and uncontrolled proliferation 23. To mitigate these risks, researchers are incorporating genetic “kill switches,” auxotrophic dependencies, and CRISPR-based self-destruct modules. While these strategies are elegant safeguards, their reliability under physiological conditions remains under scrutiny. Moreover, regulatory agencies still lack standardized frameworks for evaluating genetically modified probiotics, creating uncertainty that slows clinical progression 23. In addition to safety, ethical questions persist regarding the long-term ecological consequences of introducing engineered microbes into human populations.

The development of engineered probiotics is steering toward precision microbiome medicine 24. By integrating metagenomics, metabolomics, and machine learning, it may soon be possible to design probiotic interventions tailored to the unique microbiome and genetic profile of each patient 25. Furthermore, combining engineered probiotics with complementary modalities such as bacteriophage therapy or microbial-metabolite supplementation could enable multifunctional therapeutic platforms capable of simultaneous diagnosis, treatment, and real-time monitoring within a single biological system. Critically, the success of engineered probiotics will hinge not only on technological ingenuity but also on addressing translational realities, including manufacturing scalability, reproducibility in heterogeneous patient populations, and alignment with regulatory standards 23. If these hurdles are surmounted, engineered probiotics could emerge as a cornerstone of next-generation therapeutics, bridging microbiome science, synthetic biology, and personalized medicine in ways that conventional drugs cannot yet achieve.

Bacteriophage Therapy: The Role of Phages as Natural Antibacterial Agents

The escalating global crisis of antimicrobial resistance has re-energized interest in bacteriophages—viruses that specifically infect bacteria—as therapeutic alternatives to conventional antibiotics 26. Unlike broad-spectrum antimicrobials, bacteriophages exhibit extraordinary host specificity, selectively eliminating pathogenic bacteria while sparing beneficial commensals 26,27. This precision, coupled with their capacity to self-amplify at the site of infection, positions phages as promising candidates for next-generation antimicrobials. Nevertheless, despite more than a century of investigation, their integration into mainstream medicine remains limited, a consequence of both biological complexity and regulatory uncertainty that distinguish phages from conventional therapeutics.

Phages possess several unique attributes that directly address the limitations of antibiotics. Their high specificity minimizes collateral damage to the microbiota, thereby reducing the risk of dysbiosis-associated diseases 28. Their ability to replicate in situ generates a self-limiting therapeutic response, as viral amplification declines once the target pathogen has been eradicated. Furthermore, phages can co-evolve with their bacterial hosts, theoretically mitigating the evolutionary arms race that compromises antibiotic efficacy 29,30. Recent advances in synthetic biology now permit the engineering of phages with expanded host range, increased lytic efficiency, and the capability to deliver CRISPR-Cas payloads that selectively disable bacterial resistance genes 31. However, the very specificity of phages—once considered an advantage—also represents a major limitation. A single phage preparation is frequently insufficient to control heterogeneous or rapidly mutating bacterial populations, necessitating phage cocktails or personalized formulations; these requirements complicate regulatory approval and large-scale deployment 28.

Bacteriophage therapy has demonstrated promise in clinical scenarios in which antibiotics have failed, including multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections 32, chronic Staphylococcus aureus wound infections 33, and refractory Klebsiella pneumoniae sepsis 34. Compassionate-use cases have revealed life-saving outcomes, particularly in otherwise untreatable infections. Beyond infectious disease, phages are being explored as tools to modulate the microbiome, selectively depleting pathobionts implicated in inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, and even cancer progression 35. Nonetheless, most available evidence remains anecdotal or restricted to early-phase clinical studies, and results are frequently inconsistent owing to variations in phage selection, dosing, delivery route, and patient microbiome context 36. From a translational perspective, existing regulatory frameworks are poorly suited to living, evolving biological entities. In contrast to small-molecule drugs, phages lack uniformity, and their personalization challenges current manufacturing and approval pathways 37. Recent proposals suggest that phage therapy should be regulated similarly to biologics or even autologous cell therapies; however, international consensus has yet to be achieved.

Microbiome-derived metabolites: mechanistic mediators and therapeutic frontiers

The human microbiome is increasingly recognized as a metabolic organ in its own right, serving as an adaptive biochemical interface that continuously interacts with host physiology 38. Beyond the tangible presence of engineered probiotics and bacteriophages, the microbiome’s therapeutic potential is largely driven by its vast metabolic repertoire. These metabolites constitute the “third pillar” of microbiome-based therapeutics, acting as molecular bridges between microbial activity and host responses 39. Several studies demonstrate that these molecules modulate immune function, energy metabolism, neurochemical signaling, and host resilience to disease 40,41,42. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—particularly butyrate, propionate, and acetate—have been most extensively studied. Generated through bacterial fermentation of complex carbohydrates, SCFAs are key energy sources for colonocytes and play vital regulatory roles in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity 43. Butyrate, in particular, has attracted attention for its dual role as an energy substrate and signaling molecule 44. It modulates host gene expression through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition and activation of the G-protein-coupled receptors GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109A 45. These mechanisms converge to reinforce tight-junction assembly, promote mucin synthesis, and suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 46. At the systemic level, SCFAs contribute to glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism by modulating insulin sensitivity and adipogenesis 47. Experimental models have shown that butyrate supplementation can ameliorate colitis, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, highlighting its potential as an immune-metabolic modulator 48,49. However, clinical translation has been limited by butyrate’s chemical instability, unpleasant odor, and rapid absorption in the upper intestine, thus preventing adequate delivery to the distal colon, which is its primary site of action 50.

To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed several formulation strategies to stabilize and target SCFAs. Encapsulation in polymeric or lipid-based nanoparticles, esterification into prodrug forms, and integration into dietary fibers that release butyrate upon microbial fermentation have shown promise 51,52. In parallel, synthetic biology has opened a transformative avenue: genetically engineered probiotic strains capable of producing butyrate or propionate within the gastrointestinal tract in situ 8. These living delivery systems ensure localized, sustained production of metabolites and circumvent the pharmacokinetic constraints associated with exogenous supplementation. For instance, engineered Lactobacillus and Bacteroides species have been programmed to produce butyrate in response to environmental triggers such as pH or inflammation, offering precision control over metabolite biosynthesis within the gut 53. This integration of synthetic biology with natural metabolic signaling represents a new frontier in personalized microbiome therapeutics.

Secondary bile acids (SBAs) are generated through microbial biotransformation of host-derived primary bile acids. This process, mediated primarily by Clostridium, Eubacterium, and Bacteroides species, yields metabolites such as deoxycholic acid (DCA), lithocholic acid (LCA), and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) 54,55. SBAs serve as potent ligands for nuclear receptors, including the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), and for the membrane-bound G-protein-coupled receptor TGR5, thereby regulating host lipid and glucose metabolism and exerting profound immunomodulatory effects 56. FXR activation by SBAs suppresses lipogenic gene expression and improves insulin sensitivity, whereas TGR5 signalling initiates anti-inflammatory cascades via the cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway 57,58. Collectively, these mechanisms modulate metabolic homeostasis and immune tolerance, supporting therapeutic targeting of bile-acid pathways in disorders such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and metabolic syndrome. Bile acids also influence gut microbial composition through feedback inhibition of bacterial growth, creating a self-regulating ecological loop 59. Therapeutic manipulation of bile acids must therefore balance their beneficial signalling functions against their potential cytotoxicity, as excessive accumulation of hydrophobic SBAs can provoke oxidative stress and DNA damage in epithelial cells. Despite rapid conceptual advances, several translational challenges remain. A principal limitation is the absence of standardised pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models for these metabolites. Unlike conventional drugs, they undergo rapid turnover, exhibit variable absorption, and are subject to extensive host–microbiota co-metabolism 60. Systemic concentrations are further modulated by dietary factors, antibiotic exposure, and circadian rhythmicity 61. Additional obstacles relate to formulation and stability: short-chain fatty acids are volatile and malodorous; bile acids are amphipathic and potentially irritant; and indole derivatives are chemically labile 62. Addressing these issues will require sophisticated strategies, including encapsulation within biopolymer matrices, conjugation to protective moieties, and deployment of metabolite-producing microbial consortia.

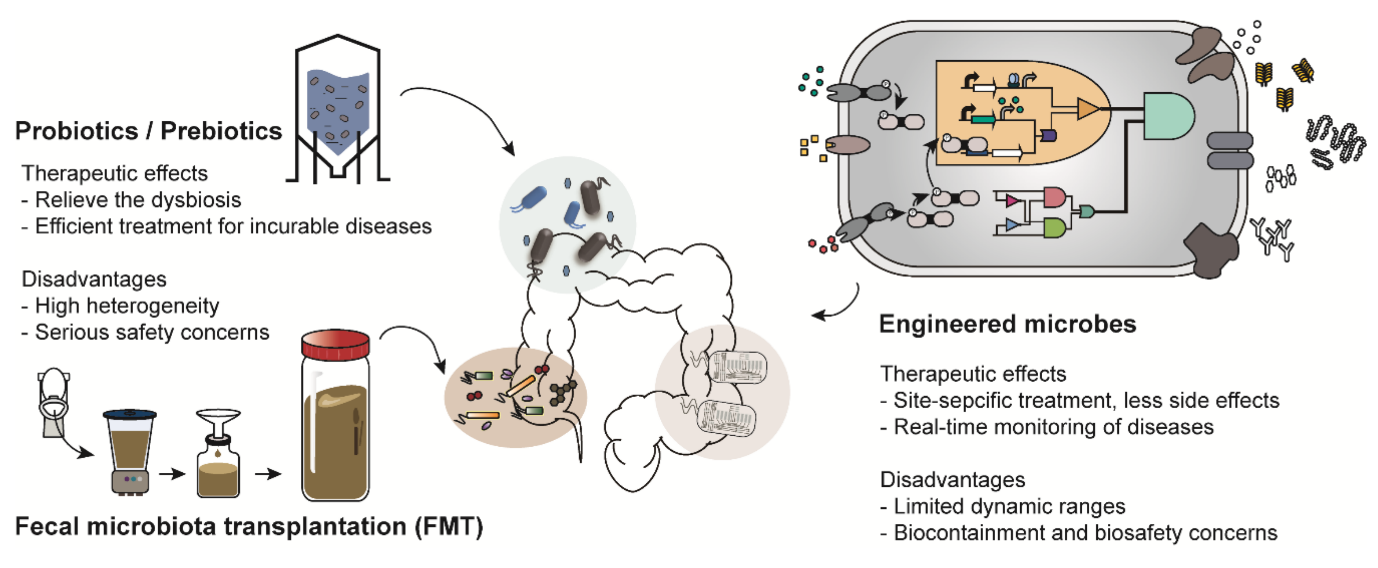

Synergistic Strategies Combining Engineered Probiotics and Bacteriophages

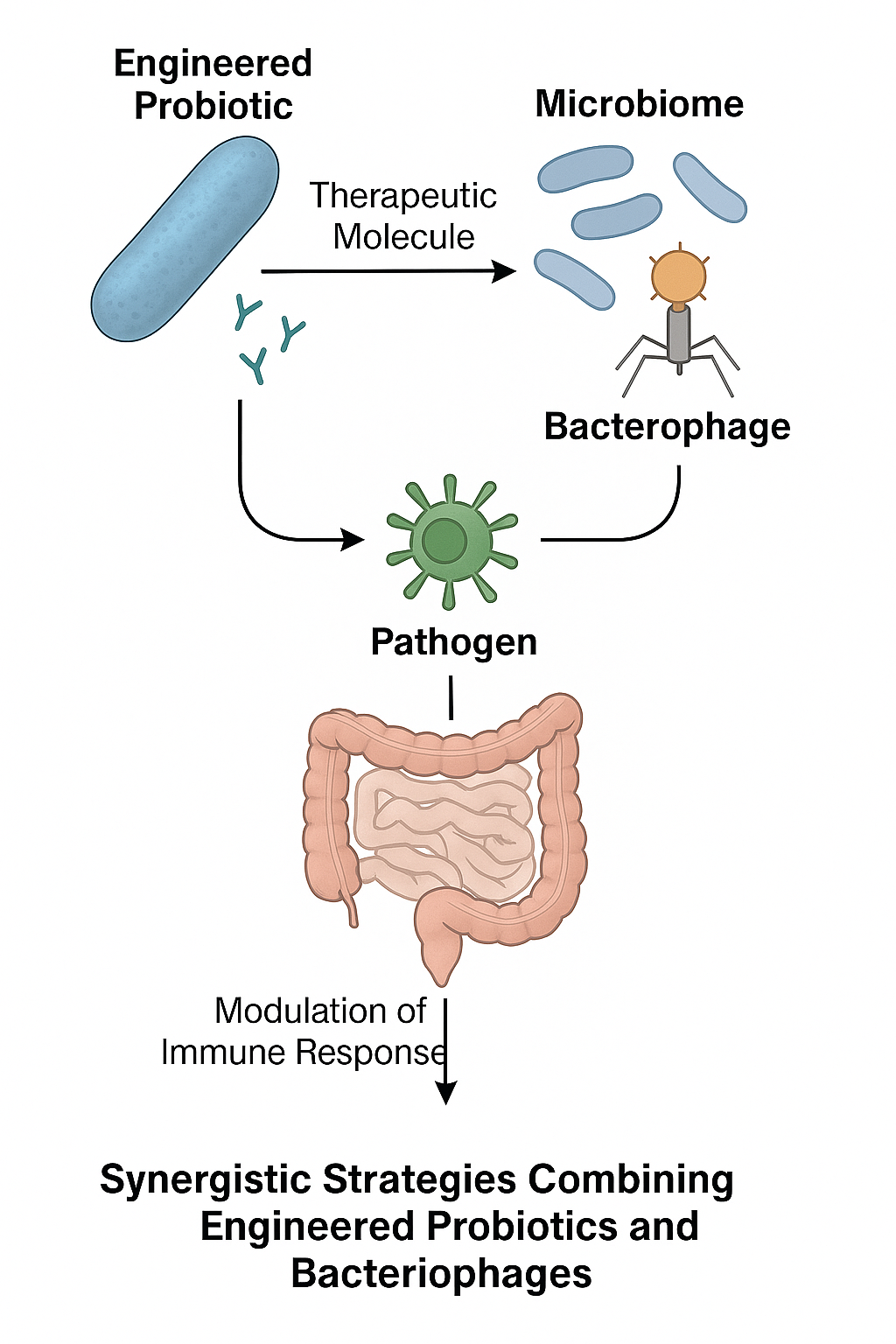

Although engineered probiotics and bacteriophages have traditionally been investigated as separate therapeutic modalities, their integration into coordinated regimens offers a transformative avenue for microbiome-based interventions. Pre-clinical studies have already examined the combined use of engineered probiotics and bacteriophages 63,64,65. Engineered probiotics serve as a stable, colonizing chassis that can sense host cues and secrete therapeutic molecules 66, whereas phages provide highly selective, self-amplifying antibacterial activity 34. Integrating these modalities can therefore compensate for the limitations inherent to each: phages offset the limited colonization and functional scope of probiotics, while engineered probiotics help counteract the narrow host range and resistance challenges associated with phages (Figure 3). Conceptually, this paradigm signals a shift from single-agent interventions toward living therapeutic consortia, capable of dynamic, multi-layered modulation of the microbiome 67.

Conceptual framework for synergistic therapy combining engineered probiotics and bacteriophages. This illustration depicts a potential integrated strategy where engineered probiotics and bacteriophages function cooperatively. Engineered probiotics can act as localized delivery vehicles or sensing platforms, while bacteriophages provide targeted, self-amplifying antibacterial activity. Their combination is designed to overcome individual limitations, such as a probiotic's functional scope or a phage's narrow host range, enabling dynamic and multi-layered modulation of the microbiome for complex therapeutic goals.

Engineered probiotic strains can serve as delivery vehicles for bacteriophages or phage-derived proteins, enabling targeted release within defined niches such as the inflamed gut or tumor microenvironment 68. Conversely, bacteriophages can selectively clear pathogenic strains that compete with or suppress probiotic colonization, thereby creating ecological space that allows engineered probiotics to establish sustained colonization 69. Importantly, these interactions can be rationally designed through synthetic consortia engineering, enabling both components to communicate via quorum-sensing signals or metabolite-mediated feedback loops, thereby achieving coordinated therapeutic effects. Despite their conceptual appeal, the practical implementation of combined probiotic–phage therapies faces significant hurdles. Phages may inadvertently lyse probiotic strains themselves, necessitating rigorous strain–phage compatibility screening 70. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic profiles of probiotics (slow colonization) and phages (rapid clearance) are mismatched, complicating the design of dosing regimens. In addition, engineering co-dependent systems raises concerns about ecological unpredictability, as unintended horizontal gene transfer or competitive exclusion could undermine safety 71. From a translational standpoint, the regulatory burden associated with approving a multi-organism therapy is considerable, given that both engineered probiotics and phages already face scrutiny as genetically modified biologics 70.

Translational Challenges and Future Directions

Despite remarkable conceptual and experimental progress, translating microbiome-based therapeutics—whether engineered probiotics, bacteriophages, or microbial metabolites—from bench to bedside remains challenging. These obstacles are multifaceted, encompassing regulatory, ecological, manufacturing, and ethical considerations, and reflect the reality that such interventions are living, dynamic systems rather than static pharmaceutical compounds. Unlike conventional small molecules, living therapeutics lack chemical uniformity 72. Engineered probiotics exhibit variable colonization capacities that depend on host genetics, diet, and resident microbiota, whereas bacteriophage efficacy is constrained by bacterial strain diversity and rapid co-evolution 73. Microbiome-derived metabolites likewise display context-dependent bioactivity, and inter-individual variability complicates dose–response prediction. The absence of standardized production and quality-control frameworks contributes to inconsistent outcomes across clinical trials and hampers regulatory approval 74. Accordingly, the development of robust manufacturing pipelines, validated biomarkers of efficacy, and predictive preclinical models will be essential to enhance reproducibility.

The ecological consequences of introducing engineered living therapeutics into human populations are still poorly understood 75. Long-term colonization with engineered probiotics could reshape microbial ecosystems in unpredictable ways, with downstream effects on immunity, metabolism, and the potential for horizontal gene transfer to environmental reservoirs 76. Similarly, widespread phage use could perturb microbial ecology at the population level. Ethical concerns also involve equity and access: will personalized microbiome therapeutics be limited to high-income settings, thereby exacerbating global health disparities? 77

The future of microbiome-based therapeutics will likely emphasize precision, personalization, and multimodality. Advances in metagenomics, metabolomics, and single-cell profiling now provide unprecedented resolution of host–microbe interactions, paving the way for tailored interventions based on individual microbial signatures. Artificial intelligence and computational modeling will assume a central role in predicting therapeutic outcomes, designing optimized microbial consortia, and anticipating ecological effects. Furthermore, the integration of engineered probiotics, bacteriophages, and microbial metabolites into unified therapeutic platforms may supply the robustness necessary to address complex, multifactorial diseases. Ultimately, the field must progress from proof-of-concept studies to rigorous, large-scale clinical trials that establish efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness across diverse populations. If these translational barriers can be systematically overcome, microbiome-based therapeutics have the potential to redefine the biomedical landscape, transforming the microbiome from a passive disease biomarker into an active target and tool for precision medicine.

Abbreviations

AI: artificial intelligence; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; DCA: deoxycholic acid; ECN: Escherichia coli Nissle 1917; FMT: fecal microbiota transplantation; FXR: farnesoid X receptor; GPR41: G-protein-coupled receptor 41; GPR43: G-protein-coupled receptor 43; GPR109A: G-protein-coupled receptor 109A; HDAC: histone deacetylase; IL-2: interleukin-2; IL-6: interleukin-6; LCA: lithocholic acid; PKA: protein kinase A; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; SBAs: secondary bile acids; TGR5: Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; Tregs: regulatory T cells; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author’s contributions

All authors have contributed equally in this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have used generative AI and/or AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission, but only to improve the language and readability of their paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.