Unravelling Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Strategies Aimed at neuroinflammation signalling pathway

- School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Health Campus, Kubang Kerian, 16150, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by progressive cognitive decline and the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau neurofibrillary tangles. Despite numerous clinical trials targeting disease modification and neuroprotection, no therapy has consistently achieved its primary efficacy endpoints. This failure can be attributed to suboptimal study designs, an incomplete understanding of the disease’s multifactorial molecular mechanisms, the paucity of reliable biomarkers, and confounding pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic effects. Beyond Aβ and tau pathology, neuroinflammation has emerged as a key driver in AD pathogenesis. Microglia and astrocytes, which play essential roles in neurotransmission and synaptic maintenance under homeostatic conditions, become aberrantly activated in AD. This shift leads to a chronic, self-perpetuating inflammatory response that aggravates Aβ and tau pathologies, thereby promoting synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Consequently, targeting neuroinflammatory signaling pathways constitutes a promising therapeutic avenue. Modulating glial cell activity and interrupting pro-inflammatory cascades may modify disease progression and yield meaningful clinical benefits. This review explores current and emerging strategies focused on neuroinflammation, underscoring their potential to reshape the treatment landscape of AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading form of dementia, responsible for approximately 60–80 % of all cases and affecting more than 55 million individuals worldwide as of 2023, a figure projected to almost double every 20 years 1. Clinically, AD is manifested by progressive cognitive decline, memory loss and deterioration of activities of daily living, ultimately leading to complete dependence and, in the terminal stage, death 2. The disease is also characterised by dysregulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly the cholinergic, glutamatergic, and serotonergic pathways, which contribute to cognitive deficits and psychiatric symptoms in patients 3. Beyond its profound impact on patients, AD imposes substantial emotional and financial strain on caregivers and families and presents an escalating challenge to healthcare systems worldwide. In 2022, the global economic cost of dementia, including Alzheimer’s, surpassed **US$**1.3 trillion and is expected to rise sharply with increasing prevalence 4.

Despite extensive research over several decades, a definitive cure for AD remains elusive. Currently approved treatments offer only limited symptomatic relief and fail to modify the underlying disease process. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved four pharmacologic agents for AD management: three cholinesterase inhibitors (rivastigmine, galantamine, and donepezil) and one N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, memantine. However, none of these agents have demonstrated the ability to cure the disease or prevent its progression 5. Notably, memantine—approved in 2003—remains the most recent addition to the therapeutic armamentarium, highlighting the prolonged stagnation in treatment innovation over the past two decades. During this time, numerous investigational drugs have undergone clinical evaluation, yet most have failed to demonstrate efficacy sufficient for approval. The repeated setbacks in clinical trials, particularly those targeting amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau pathology, may be attributed to factors such as inadequate trial design, limited understanding of AD’s multifactorial pathobiology, a lack of robust biomarkers for early detection and disease tracking, and unforeseen interactions between therapeutic agents and the disorder’s complex mechanisms.

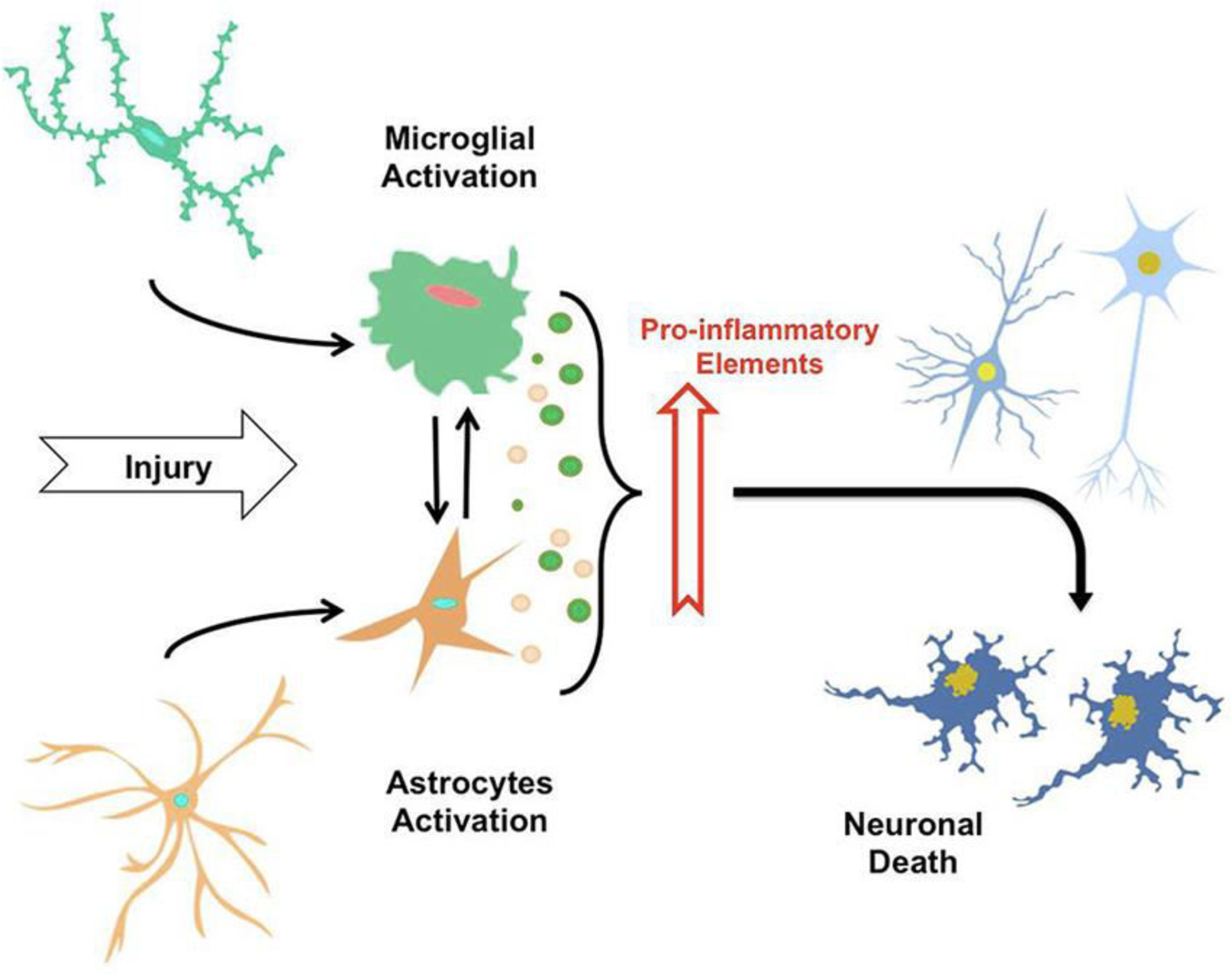

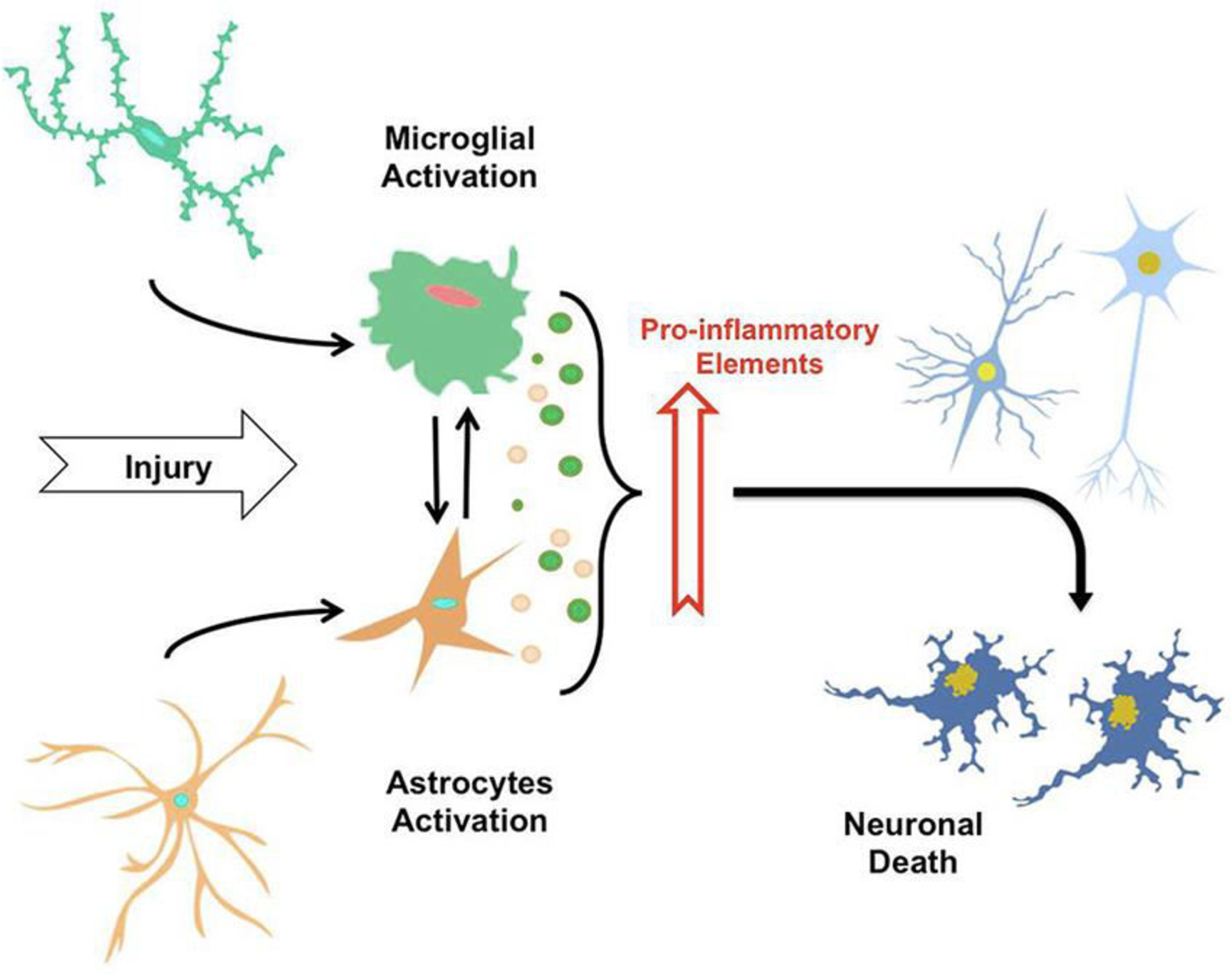

While Aβ plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles have traditionally dominated the landscape of AD research, increasing evidence highlights the critical role of neuroinflammation in disease pathogenesis. Microglia and astrocytes, the principal immune cells of the central nervous system, play essential roles in maintaining synaptic homeostasis and supporting neuronal function under physiological conditions. However, in the context of AD, these glial cells undergo a pathological transformation, sustaining chronic, exaggerated inflammatory responses. This maladaptive activation synergizes with Aβ and tau pathology, driving synaptic dysfunction, neuronal injury, and accelerating neurodegeneration in a self-perpetuating cycle.

Given this emerging understanding, targeting neuroinflammatory signalling pathways offers a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention. Modulating glial cell activity and attenuating pro-inflammatory cascades may not only mitigate neuronal damage but also potentially slow or halt disease progression. This review aims to explore the evolving landscape of therapeutic strategies directed at neuroinflammatory mechanisms in AD, shedding light on novel targets, current challenges, and future perspectives in the quest for effective disease-modifying treatments.

Compared with prior reviews 6,7,8, this article provides several additional insights. Specifically, we present a head-to-head comparative analysis of ongoing and recent clinical trials targeting neuroinflammation, a quantitative overview of the therapeutic pipeline, and an in-depth discussion of blood–brain barrier (BBB) delivery hurdles. Furthermore, our glial-centric perspective highlights astrocyte and microglia reprogramming strategies, while also exploring next-generation modalities such as gene editing, RNA-based therapies, and immune checkpoint modulation. These elements collectively distinguish this review and provide a forward-looking framework for future research and clinical translation.

Methodology of Literature Search

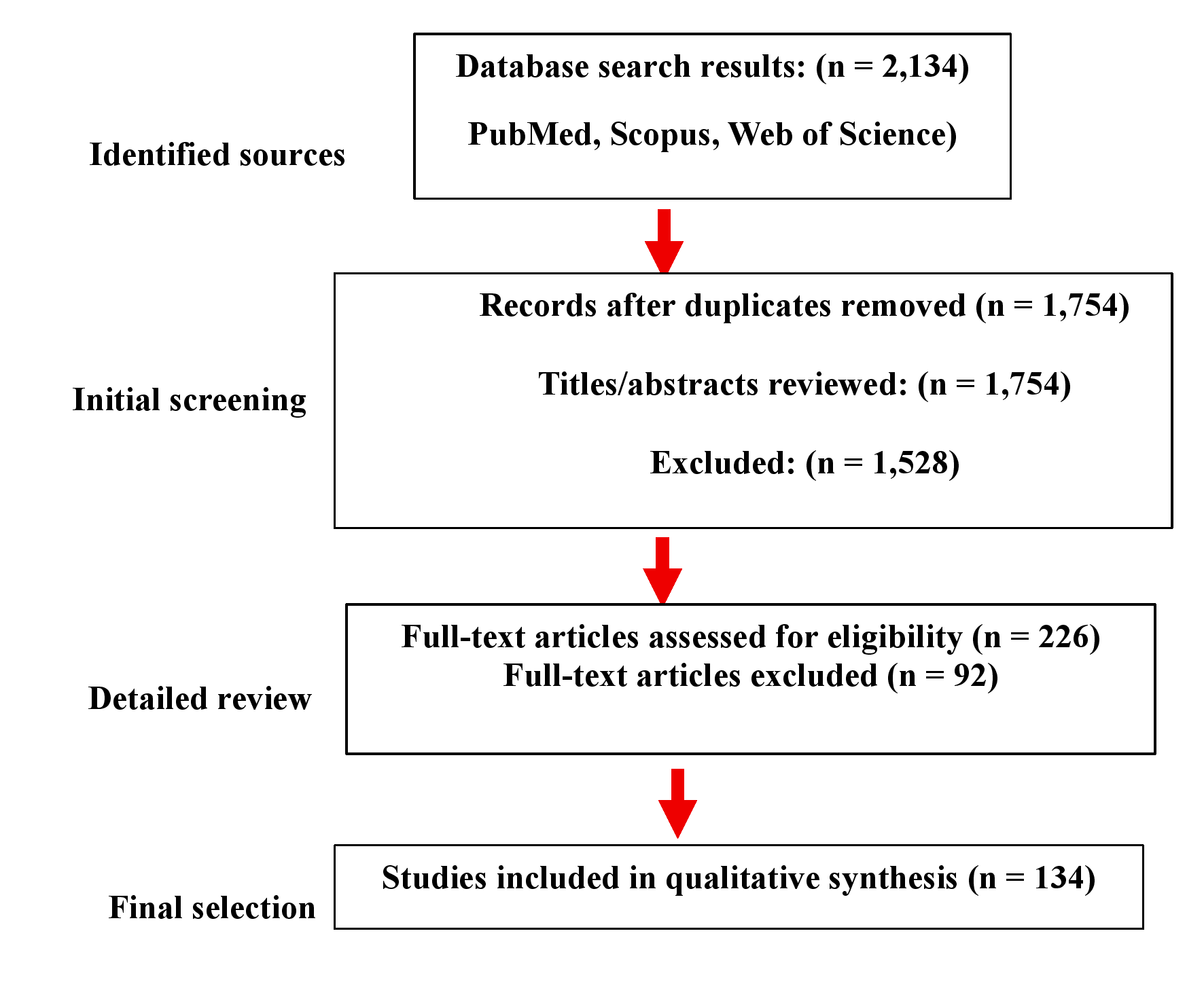

To ensure comprehensive and unbiased coverage, we conducted a structured literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science for studies published between January 2000 and June 2025. Search terms comprised combinations of “Alzheimer’s disease,” “neuroinflammation,” “microglia,” “astrocytes,” “therapeutic strategies,” “clinical trial,” “immunotherapy,” “RNA-based therapy,” “NLRP3,” and “TREM2.” Inclusion criteria were limited to peer-reviewed original research articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical trial reports pertinent to (AD)-related neuroinflammatory mechanisms or interventions. Exclusion criteria included conference abstracts, non-peer-reviewed articles, studies unrelated to AD-associated neuroinflammation, and non-English language publications. Figure 1 shows the literature selection process for this narrative review of therapeutic strategies targeting neuroinflammatory signaling pathways in AD.

PRISMA-style literature selection process for the narrative review of Therapeutic Strategies Aimed at Neuroinflammation Signalling Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease

Pathophysiology of Neuroinflammation in AD

Neuroinflammation has emerged as a central pathological feature of AD, acting as both a driver and a consequence of amyloid and tau pathology. Unlike the transient, protective response characteristic of acute inflammation, chronic neuroinflammation in AD results in sustained glial activation, generating a deleterious milieu that exacerbates neuronal injury and accelerates disease progression. Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, are first responders to Aβ deposition. Upon activation, microglia adopt a pro-inflammatory (M1) phenotype and secrete cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6); these mediators promote synaptic dysfunction, oxidative stress and neuronal death 9,10. While microglia can polarise toward an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype that supports tissue repair and Aβ clearance, chronic stimuli in AD preferentially maintain the detrimental M1 state. Astrocytes, once regarded primarily as metabolic and structural support cells, are now recognised as key effectors of neuroinflammation. Reactive astrocytes, frequently located adjacent to amyloid plaques, augment inflammation via cytokine and chemokine release and further disrupt BBB integrity, thereby facilitating peripheral immune-cell infiltration 11.

Multiple intracellular signalling pathways amplify these neuroinflammatory cascades. Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), a master regulator of inflammation, is activated by Aβ through pattern-recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), particularly TLR4, culminating in the transcription of numerous pro-inflammatory genes 12. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs)—extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38—are similarly activated in glia and neurons in AD; their engagement increases cytokine production and tau phosphorylation, thereby amplifying pathology 13. The NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is triggered by Aβ in microglia, resulting in pro-caspase-1 cleavage and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18; this axis is pivotal to the chronic inflammatory milieu of AD 14. The Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway likewise contributes to AD-related neuroinflammation by modulating cytokine signalling and glial activation 15.

Chronic oxidative stress—largely deriving from sustained inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction—induces lipid peroxidation, DNA damage and additional neuronal loss, thereby establishing a vicious cycle in which inflammation and oxidative injury mutually reinforce one another 16. Collectively, neuroinflammation in AD constitutes not merely a secondary consequence of protein aggregation but a primary pathogenic driver, and thus represents a compelling therapeutic target for disease-modifying interventions aimed at preserving neuronal viability. The neuroinflammatory mechanisms in AD are summarised in Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the neuroinflammatory cascade in Alzheimer’s disease. The artwork is original and created by the authors, integrating concepts adapted from published literature

Crosstalk Between Neuro-Immune Pathways in AD

Beyond isolated signalling cascades, AD neuroinflammation also arises from complex crosstalk between innate immune pathways.

TREM2–DAP12–SYK axis

An illustrative example is the Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2–DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa–spleen tyrosine kinase (TREM2–DAP12–SYK) signalling axis, which regulates microglial survival, lipid metabolism, and the phagocytic clearance of Aβ 17. The TREM2–DAP12–SYK signalling axis is pivotal in coupling microglial activation to NLRP3 inflammasome priming 18. Following recognition of ligands such as lipids, apoptotic debris, or Aβ aggregates, TREM2 recruits DAP12, an adaptor protein containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs). Phosphorylation of these motifs by Src-family kinases enables recruitment and activation of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK). Activated SYK then initiates downstream cascades, including the PI3K–Akt, ERK, and NF-κB pathways, thereby upregulating transcription of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β and providing the necessary priming signal (Signal 1) for inflammasome assembly 19. Upon exposure to secondary triggers such as mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), potassium (K) efflux, or lysosomal disruption, the primed NLRP3 complex oligomerizes and recruits caspase-1, leading to the cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms 14. In the context of neurodegeneration, particularly AD, this pathway highlights how microglial sensing of Aβ through TREM2 not only promotes phagocytic clearance but also intensifies NLRP3-driven neuroinflammation, amplifying IL-1β release and contributing to neuronal dysfunction and disease progression 20.

Type-I interferon (IFN-I)

An additional critical facet of neuro-immune crosstalk in AD is the type I interferon (IFN-I) response. Under physiological circumstances, transient IFN-I signalling is indispensable for antiviral defence and the preservation of immune homeostasis 21. Conversely, in the AD brain, sustained IFN-I activity triggers the JAK/STAT signalling cascade, thereby promoting microglial proliferation, augmenting astrocytic reactivity, and perpetuating cytokine release 22. In particular, IFN-I-mediated STAT1/3 activation acts synergistically with NF-κB transcriptional programmes and NLRP3-inflammasome priming, thereby escalating the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 23. This feed-forward loop not only amplifies neuroinflammation but also impairs synaptic plasticity and neuronal integrity, fostering excitotoxicity and network dysfunction 21,22. Importantly, accumulating evidence indicates that IFN-I responses constitute a molecular bridge between innate immune sensing and maladaptive neurotoxicity, identifying this pathway as a promising therapeutic target for limiting glial over-activation and neurodegeneration in AD 24.

APOE genotype

Genetic risk factors—most notably the apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype—further modulate the trajectory of neuroinflammatory cascades in AD. The APOE ε4 isoform, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, not only disrupts lipid transport and cholesterol homeostasis but also profoundly alters microglial transcriptional programs, diverting them toward a pro-inflammatory, disease-associated state 25. This impact is further intensified when APOE ε4 coincides with defective TREM2 signalling, which reduces microglial phagocytic capacity and augments maladaptive cytokine release, thereby sustaining a self-perpetuating inflammatory milieu 26,27. Concurrently, TLR pathways—particularly TLR2 and TLR4—are chronically engaged by aggregates, extracellular debris, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as oxidised lipids and mitochondrial fragments 28,29. Activation of these receptors drives NF-κB-dependent transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators and synergises with NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome priming, thereby amplifying the production of cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α 28,29. Collectively, the convergence of APOE ε4-directed microglial reprogramming, impaired TREM2-dependent lipid sensing, and chronic TLR–NF-κB activation establishes a vicious cycle of innate immune activation, synaptic injury, and progressive neuronal dysfunction in AD 26,29.

Taken together, these interconnected pathways demonstrate that AD-related neuroinflammation is not a linear cascade but a network of converging signals. The M1/M2 polarisation spectrum constitutes the phenotypic read-out of this integration and is dictated by the balance among phagocytic-receptor signalling, inflammasome priming, interferon-JAK/STAT activity, and APOE-driven metabolic cues. Appreciating this crosstalk provides a more nuanced framework for therapeutic intervention, thereby distinguishing the present review from prior descriptive accounts.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Neuroinflammation

Given the central role of neuroinflammation in AD pathogenesis, increasing efforts have been directed at identifying therapeutic strategies that modulate inflammatory signalling. These approaches range from repurposed anti-inflammatory agents to targeted molecular therapies and natural compounds that attenuate glial activation and inflammatory cytokine production.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs were among the earliest pharmacological interventions evaluated for AD, owing to epidemiological studies that suggested reduced AD incidence among long-term NSAID users. These agents inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes, particularly COX-2, which is up-regulated in AD brains and contributes to prostaglandin-mediated neuroinflammation 30. However, clinical trials have yielded mixed outcomes. Although NSAIDs such as naproxen and celecoxib demonstrated modest preventive potential in preclinical AD models, their efficacy in symptomatic AD has been limited, possibly because treatment commenced at later disease stages 31. In clinical studies, NSAIDs likewise appear to confer greater benefit in preventing the transition from cognitive impairment to AD than treating established disease, and additional research is needed 31. A Phase I trial of salsalate is ongoing, and preliminary data indicate CNS anti-inflammatory effects. Phase II studies evaluating the leukotriene-receptor antagonist montelukast and the p38 MAP-kinase inhibitor neflamapimod (VX-745) are also in progress 32. Overall, NSAIDs may hold more promise as preventive agents than as treatments, yet definitive disease-modifying effects have not been demonstrated.

In the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT; n = 2,528; naproxen 220 mg twice daily or celecoxib 200 mg twice daily for 2–3 years), no cognitive benefit was detected 33. A smaller randomised controlled trial (n = 351) that evaluated rofecoxib 25 mg/day or naproxen 220 mg twice daily in patients with mild-to-moderate AD for 12 months likewise failed to attenuate decline on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) or the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) 34. This discrepancy probably reflects the later disease stage and shorter treatment exposure in the latter study.

Inhibitors of Microglia Activation

Modulating microglial hyperactivation represents a promising therapeutic strategy for neuroinflammatory disorders. Inhibitors of the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R), such as PLX3397, effectively suppress microglial proliferation and attenuate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Preclinical studies demonstrate that CSF1R blockade mitigates Aβ deposition and preserves synaptic integrity 35. Similarly, minocycline, an inhibitor of microglial activation, reduces lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation and associated cognitive deficits in rodent models 36. Beyond CSF1R signaling, TREM2 has emerged as a pivotal regulator of microglial phenotypes. Augmenting TREM2 activity enhances phagocytosis while suppressing pro-inflammatory signaling, underscoring its potential as a disease-modifying target in neurodegenerative conditions 17,18,20,35,37.

In APP/PS1 mice, PLX3397-mediated CSF1R inhibition markedly reduces microgliosis and Aβ pathology 35; however, clinical translation remains limited. Conversely, minocycline improves cognitive performance in LPS-challenged rats 36, yet human trials have yielded inconsistent results, probably owing to delayed treatment initiation and insufficient central nervous system penetration.

Natural Compounds with Anti-Inflammatory Actions

Curcumin, a polyphenolic compound derived from turmeric, inhibits NF-κB and MAPK signalling, reduces astrocytic and microglial activation, and suppresses IL-1β and TNF-α expression. It also interferes with Aβ aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation 38,39,40. In aged experimental models, chronic curcumin administration significantly decreased lipid peroxidation and lipofuscin accumulation while simultaneously enhancing superoxide dismutase and Na/K-ATPase activities 40.

Resveratrol, a stilbene-type polyphenol abundant in grapes and red wine, exerts potent antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects. It activates sirtuin-1 (SIRT1), which deacetylates transcription factors such as p53, the FOXO family, and NF-κB, thereby attenuating pro-apoptotic signalling 41. SIRT1 activation also suppresses NF-κB transcriptional activity and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Consistent with these mechanisms, resveratrol has shown promise in pre-clinical models and early-phase clinical studies by modulating inflammatory and amyloid biomarkers 42.

Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), exert anti-inflammatory actions by competing with arachidonic acid and serving as precursors for specialised pro-resolving mediators (resolvins). These mediators dampen pro-inflammatory cytokine release and glial activation, and supplementation has conferred cognitive benefits in early-stage AD 43.

Nevertheless, clinical translation of these anti-inflammatory agents has been disappointing. Although curcumin and resveratrol display robust antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in vitro and in animal models, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have yielded predominantly negative or inconclusive results, owing in part to limited BBB permeability, poor oral bioavailability, and rapid systemic metabolism 42,44,45. Similarly, RCTs of NSAIDs such as naproxen and celecoxib were terminated early or showed no cognitive benefit, highlighting the difficulty of repurposing peripheral anti-inflammatories for central nervous system indications 33,34. Contributing factors include sub-optimal dosing, brief treatment duration, and heterogeneous participant populations, which collectively hinder detection of modest therapeutic effects. These findings underscore the need for improved delivery platforms (e.g., nanoparticles, intranasal formulations), rigorous trial design, and combination strategies to overcome the limitations of single-agent therapy.

In a 52-week, phase-II resveratrol trial (n = 119), cerebrospinal fluid Aβ levels and regional brain volumes were altered without parallel cognitive improvement 41,42. A 24-week curcumin RCT (n ≈ 34) likewise failed to improve ADAS-Cog scores 40. By contrast, omega-3 supplementation in individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early AD (n = 46) produced modest cognitive gains 43, reinforcing the importance of disease stage and treatment duration in determining therapeutic response.

TREM2–DAP12–SYK Modulation

However, emerging evidence suggests that therapeutic benefit in AD may be greatest when interventions target key nodes of pathway crosstalk, where multiple signaling axes converge to perpetuate glial dysfunction46. One such node is the TREM2–DAP12–SYK pathway, which regulates lipid sensing, phagocytosis, and microglial state transitions47. TREM2 agonists and monoclonal antibodies are under investigation as strategies to enhance microglial clearance of amyloid deposits and cellular debris, thereby restoring homeostatic surveillance48. By promoting lipid metabolism, cholesterol efflux, and debris processing, TREM2 activation not only attenuates Aβ accumulation but also indirectly limits NLRP3-inflammasome priming and downstream IL-1β secretion49. Consequently, microglia shift from a chronically activated, M1-like pro-inflammatory phenotype to a more homeostatic or reparative state49. Early-phase biologics such as AL002, a humanized agonistic anti-TREM2 antibody, have already entered clinical evaluation and have demonstrated favorable target engagement and safety profiles in first-in-human trials49. These findings underscore the therapeutic promise of TREM2-directed interventions for modulating amyloid pathology and recalibrating microglial immune tone, thereby addressing both innate immune dysregulation and neuroinflammatory amplification characteristic of AD48,49. Preclinical activation of TREM2 with antibodies such as AL002 reduces Aβ plaque burden and restores microglial homeostasis48. By contrast, early-phase human studies have thus far focused primarily on safety and target engagement rather than clinical efficacy49, discrepancies that are largely attributable to differences in trial phase and selected endpoints (biomarker versus clinical outcomes).

NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors

The NLRP3 inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that is activated within microglia by Aβ, mitochondrial stress signals and defective lipid sensing, serves as a pivotal trigger for caspase-1 activation and the subsequent maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, thereby fueling chronic neuroinflammation in AD. Small-molecule inhibitors, such as MCC950, selectively impede NLRP3 assembly, thereby preventing caspase-1 activation and downstream cytokine processing. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that MCC950 mitigates microgliosis, decreases Aβ deposition and enhances cognitive performance in transgenic AD models 50,51. Importantly, NLRP3 inhibition represents a convergent node that intersects with TREM2 dysfunction, aberrant TLR–NF-κB signaling, and mitochondrial stress-derived danger signals, including ROS and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release 52,53. By interrupting this feed-forward loop, NLRP3 blockade not only dampens microglial and astrocytic overactivation but also ameliorates synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline. MCC950 and next-generation inflammasome inhibitors are progressing through translational pipelines, highlighting their potential to re-establish a more homeostatic neuroimmune milieu in AD 50,51,52,53. Consistent with these findings, MCC950 robustly suppressed IL-1β signaling, diminished Aβ burden and improved cognitive outcomes in multiple transgenic mouse models of AD 50,51. Nevertheless, clinical development remains in its infancy, and the apparent translational gap between animal and human data largely reflects differences in trial maturity and a current emphasis on safety assessment rather than an absence of therapeutic efficacy 52,53.

JAK/STAT Pathway Blockade

The JAK/STAT signaling cascade is a central mediator of glial proliferation and cytokine-driven neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative contexts. In preclinical models, pharmacological inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 has been shown to attenuate neuroinflammation, reduce gliosis, and improve learning and memory outcomes 54. Aberrant IFN-I signaling perpetuates glial activation through persistent STAT1/3 phosphorylation, amplifying cytokine release and neurotoxic feedback loops. Small-molecule JAK2/STAT3 inhibitors, including ruxolitinib and baricitinib, have demonstrated therapeutic promise in experimental neuroinflammatory models. For example, ruxolitinib reduces microglial proliferation and suppresses TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression after spinal cord injury 55 and attenuates inflammatory gene expression in post-infectious inflammatory syndromes 56. Similarly, baricitinib reverses neurocognitive deficits and dampens neuroinflammatory cytokine release in models of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder 57. By suppressing cytokine transcription and disrupting the synergy between IFN-I–driven STAT1/3 signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, JAK/STAT blockade offers a compelling therapeutic avenue either as a monotherapy or in combination therapy to restore immune balance and limit glial-mediated neurodegeneration.

JAK inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, have demonstrated potent glial anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in preclinical models of AD, including suppression of microglial activation and downstream cytokine signaling 55. However, human investigations to date have been limited primarily to early-phase or biomarker-focused studies, with no conclusive evidence of cognitive benefit. This discrepancy largely stems from differences in study design and endpoints; preclinical studies typically assess neuroinflammatory and molecular outcomes, whereas clinical trials emphasize cognitive and functional measures and are constrained by limited treatment duration and subtherapeutic central exposure during early human testing.

APOE-Genotype-Specific Strategies

The APOE4 allele is the strongest, most consistently validated genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, conferring a three- to twelve-fold increase in risk relative to APOE3 or APOE2 carriers 58. Beyond its canonical role in cholesterol and lipid transport, APOE4 profoundly influences microglial transcriptional programs, driving them toward pro-inflammatory, disease-associated phenotypes 59. This maladaptive re-programming disrupts lipid metabolism, impairs Aβ clearance, and acts synergistically with TREM2 dysfunction to amplify neuroinflammatory cascades 59. To counteract these effects, several APOE-directed therapeutic strategies are currently under development. APOE mimetic peptides, such as CS-6253, restore lipid efflux and normalize cholesterol homeostasis, thereby indirectly attenuating microglial activation and synaptic toxicity 58. Gene-therapy approaches aim to convert APOE4 to a more protective, APOE2-like profile, thereby recalibrating the balance between lipid metabolism and immune regulation 60. In parallel, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are being investigated to selectively lower APOE4 expression, thereby reducing its pathogenic gain-of-function effects and mitigating downstream inflammatory signalling 61. Collectively, these interventions target the metabolic–immune interface, positioning APOE modulation as a strategy not only to enhance amyloid clearance but also to indirectly regulate TREM2-dependent phagocytosis and NF-κB-driven cytokine release, thus dampening the chronic neuroinflammation that characterises APOE4-associated AD 58,59,60,61. APOE mimetics and antisense oligonucleotides have demonstrated promising effects in preclinical models, including modulation of lipid metabolism, reduction of amyloid deposition, and attenuation of microglial activation 58. These agents are designed to restore homeostatic APOE function, enhance lipid transport, and mitigate neuroinflammation—key processes implicated in AD pathogenesis. However, the ongoing phase 1 clinical trials are focused primarily on evaluating safety, tolerability, and target engagement rather than cognitive outcomes. Consequently, the current evidence of efficacy is confined to biomarker improvements, reflecting the early stage of clinical translation and the need for longer-term trials that assess cognitive and functional endpoints.

TLR–NF-κB Modulators

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), particularly TLR2 and TLR4, act as innate immune sensors that recognize aggregated Aβ, oxidized lipids, and mitochondrial debris, thereby driving persistent activation of the NF-κB pathway in AD 62. Chronic engagement of these receptors results in transcriptional up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, which sustain microglial activation, astrocytic reactivity, and neuronal injury 63,64.

Pharmacological modulation of TLR signalling represents a promising upstream strategy for attenuating innate immune overactivation. Resatorvid (TAK-242), a selective TLR4 inhibitor, disrupts receptor–adaptor interactions, limits NF-κB nuclear translocation, and diminishes downstream cytokine production, yielding neuroprotective effects in preclinical AD models 65.

Importantly, TLR modulation may be particularly relevant in APOE4 carriers, who exhibit impaired lipid metabolism and reduced amyloid clearance 66. In this genetic context, excess lipid debris and amyloid aggregates serve as persistent TLR ligands, further amplifying microglial activation and neurotoxic feedback loops 66. Natural compounds with TLR-modulating properties, such as curcumin and resveratrol, may also provide adjunctive benefits, although their poor bioavailability hampers clinical translation 67. Collectively, these findings identify TLR–NF-κB inhibition as a strategic intervention point that bridges amyloid pathology, genetic risk, and innate immune dysregulation, positioning TLR modulators as candidates for genotype-informed therapies in AD 62,63,64,65,66,67.

TLR4 inhibition with TAK-242 has been shown to markedly suppress Aβ-induced cytokine release and neuroinflammatory signalling in both cellular and rodent models 65, highlighting TLR4 as a critical upstream mediator linking innate immune activation to microglial-driven neurotoxicity in AD. Nevertheless, despite compelling preclinical evidence, no pivotal clinical trials have yet been conducted in AD populations. The preclinical–clinical gap likely reflects the complex and pleiotropic nature of TLR4 signalling, which participates in both protective and pathological immune responses, as well as the predominance of late-symptomatic enrolment in human studies, when neuroinflammatory cascades are already entrenched and less amenable to modulation.

In summary, neuroinflammation in AD arises from complex crosstalk among metabolic, immune, and glial pathways, and therapeutic efforts are shifting toward interventions at these convergent hubs. By targeting mechanisms such as TREM2 signalling, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, JAK/STAT pathways, and APOE-driven immune dysregulation, emerging strategies may restore immune balance and attenuate neuronal injury. Future progress will depend on improved drug delivery, rigorous clinical trial design, and combination approaches that transcend single-pathway paradigms to achieve meaningful disease modification.

Emerging and Experimental Strategies

Despite the advancements in targeting Aβ and tau pathology in AD, the persistent failure of many therapeutic candidates has shifted attention toward alternative pathological mechanisms most notably, neuroinflammation. Emerging and experimental strategies increasingly focus on modulating the immune environment of the brain, with the aim of slowing disease progression and promoting neuroprotection. Below, we outline several promising approaches currently under investigation.

Immunotherapies with Anti-inflammatory Goals (Beyond Amyloid Clearance)

Early immunotherapeutic efforts in AD primarily targeted the removal of Aβ plaques. However, recent advances have shifted towards directly modulating neuroinflammatory pathways. Persistent activation of microglia and astrocytes plays a critical role in synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss. Emerging immunotherapeutic approaches aim to reprogram microglia from a pro-inflammatory (M1-like) phenotype to an anti-inflammatory (M2-like) phenotype 9. Additionally, targeting immune checkpoints, such as the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, may help re-establish immune homeostasis within the central nervous system 68. Another promising avenue involves modulation of TREM2 signaling, a key regulator of microglial function that is involved in phagocytosis, cytokine regulation, and lipid metabolism 69. Collectively, these strategies seek to reduce neuroinflammation, enhance glial cell function, facilitate clearance of cellular debris, and support neuronal survival.

Gene Editing and RNA-Based Therapies Targeting Inflammatory Pathways

Advancements in genetic engineering have enabled the development of precise molecular tools to manipulate inflammatory signaling in the brain. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is being explored to silence genes that drive chronic inflammation, such as genes encoding components of the NLRP3 inflammasome or pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α 70. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNA interference (RNAi) technologies have been employed to reduce the expression of specific targets implicated in neurodegeneration, including tau, TREM2, and inflammatory cytokines 71,72. Although these strategies confer high specificity and are reversible, efficient delivery—particularly across the BBB—remains a major obstacle. Promising preclinical results suggest that gene-editing and RNA-based therapeutics may provide a powerful means of fine-tuning immune responses and mitigating neuroinflammatory damage in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Biologics: Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

Biologic agents, especially monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), are now being engineered to neutralize key pro-inflammatory mediators within the CNS. Anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies—already approved for autoimmune diseases—are currently being studied for their potential to attenuate CNS inflammation when delivered via BBB-penetrating formulations or by intrathecal administration 73. IL-1β and IL-6 inhibitors, such as canakinumab, have demonstrated neuroprotective potential by mitigating downstream inflammatory cascades that compromise neuronal function 74,75. These mAbs provide precise immune modulation, although there are concerns about long-term immunosuppression, CNS accessibility, and possible off-target effects. Ongoing trials are actively evaluating the feasibility of using biologics to rebalance cytokine networks involved in AD pathology.

Stem Cell Therapy: Immunomodulation Through MSCs and Neural Stem Cells

Stem cell–based therapies provide a multipronged strategy for restoring immune homeostasis, augmenting neuroprotection, and promoting tissue repair. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and other adult sources, exert potent immunomodulatory actions by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β), driving microglial polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, suppressing astrocytic activation, and attenuating oxidative stress 76,77. Neural stem cells (NSCs) not only possess the capacity to replace lost neurons but also release trophic and immunoregulatory mediators that foster neurogenesis and mitigate inflammatory processes 78. In preclinical models, stem-cell therapy has been shown to decrease glial activation, improve cognitive performance, and remodel the neuroinflammatory milieu 79. Although clinical experience remains limited, early-phase trials indicate that stem cell–based interventions may act as disease-modifying treatments capable of addressing the intricate interplay between immune dysregulation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Next-generation modalities, including CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, immune-checkpoint inhibition (anti-PD-1/PD-L1), and additional stem-cell platforms, have garnered substantial interest; however, all remain at low technology-readiness levels (TRLs) and thus warrant cautious interpretation. CRISPR/Cas9 applications in AD are currently confined to preclinical proof-of-concept studies (TRL 2–3) that target APOE4 alleles or amyloidogenic drivers 80. Immune-checkpoint modulation with anti-PD-1 antibodies has demonstrated enhanced immune surveillance and amyloid clearance in murine models, yet clinical development is still at TRL 3–4, with no large-scale efficacy data in patients 81. Stem-cell therapies, particularly MSC infusions, have advanced further, with several phase-I/II trials (TRL 4–5) confirming feasibility and safety (e.g., NCT02600130, NCT02833792); definitive efficacy signals, however, are not yet available 82. Collectively, these interventions remain experimental, and despite their promise, their readiness for routine clinical application in AD is currently limited.

To facilitate critical appraisal, we systematically assessed each therapeutic category with respect to both mechanistic plausibility and clinical maturity.

Therapeutic strategies targeting neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical maturity and key readouts

| Therapeutic Strategy | Compound / Approach | Stage of Development | Main Readouts / Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs | Naproxen, Celecoxib, Rofecoxib | Phase 3 (prevention trials); failed symptomatic AD trials | Limited cognitive benefit when given late; potential preventive effects in prodromal stages [refs: |

| Salsalate | Phase 1 | Anti-inflammatory activity; safety evaluation ongoing [refs: | |

| Montelukast, Neflamapimod (VX-745) | Phase 2 | Cognitive outcomes; CSF biomarkers of inflammation [refs: | |

| Microglial activation inhibitors | PLX3397 (CSF1R inhibitor) | Pre-clinical / early trials | Reduced microglial proliferation; ↓ Aβ burden; improved synaptic integrity [refs: |

| Minocycline | pre-clinical | Attenuation of glial activation; improved learning & memory in animal models [refs: | |

| TREM2 modulation | Pre-clinical | Enhanced microglial phagocytosis; reduced pro-inflammatory signalling [refs: | |

| NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors | MCC950 and analogues | Pre-clinical | ↓ IL-1β production; ↓ tau pathology; cognitive improvement in AD mice [refs: |

| Toll-like receptor modulators | Resatorvid (TAK-242, TLR4 inhibitor) | Pre-clinical | Reduced cytokine release; neuroprotection in animal models [refs: |

| Natural compounds | Curcumin | Phase 2 (limited trials); strong pre-clinical | ↓ NF-κB/MAPK signalling; improved mitochondrial function; modest cognitive benefit [refs: |

| Resveratrol | Phase 2 (early human studies) | SIRT1 activation; ↓ NF-κB activity; mixed cognitive outcomes [refs: | |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA) | Phase 2–3 | Improved cognition in early AD; anti-inflammatory effects [refs: | |

| JAK/STAT inhibitors | JAK2/STAT3 blockers | Pre-clinical | ↓ gliosis and cytokine production; improved learning & memory in animal models [refs: |

| Immunotherapies | PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade | Pre-clinical | Restored immune homeostasis; improved memory in AD models [refs: |

| TREM2 agonistic antibodies | Pre-clinical | Promoted microglial protective phenotype [refs: | |

| Gene/RNA-based therapies | CRISPR/Cas9 (targeting NLRP3, pro-inflammatory cytokines) | Pre-clinical | Gene silencing; reduced neuroinflammatory cascade [refs: |

| Antisense oligonucleotides / RNAi | Pre-clinical | Reduced expression of tau, TREM2, IL-1β; improved neuronal survival [refs: | |

| Biologics (cytokine neutralization) | Anti-TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., canakinumab) | Phase 2 / repurposing trials | ↓ inflammatory cytokines; preliminary cognitive outcomes; concerns on CNS delivery [refs: |

| Stem cell–based therapies | MSCs (exosome-derived) | Pre-clinical / early human (Phase 1) | ↓ glial activation; enhanced neurogenesis; improved cognition in AD models [refs: |

| Neural stem cells | Pre-clinical / early clinical | Secretion of trophic & immunomodulatory factors; safety established in Phase 1 [refs: |

In summary, these emerging strategies underscore a paradigm shift in AD research, moving beyond classical amyloid- and tau-centric targets toward a comprehensive focus on neuroinflammation. Although challenges regarding delivery, safety, and sustained efficacy persist, these innovative approaches offer realistic prospects for more effective, individualized interventions that directly address the inflammatory dimension of AD pathogenesis.

Challenges and Future Directions

The heterogeneity of the neuroinflammatory responses among individuals with AD constitutes a significant challenge to the development of effective treatments. Individual patients may exhibit disparate degrees of inflammation, influenced by genetic, environmental, and lifestyle determinants. This variability necessitates precision therapeutic strategies in which interventions are matched to the individual's specific inflammatory profile. The timing of intervention is likewise critical; early-stage intervention is likely to be more efficacious in attenuating ongoing neuroinflammation and preventing subsequent neuronal injury. Identifying the optimal window for therapeutic intervention requires comprehensive delineation of the disease's progression and the establishment of reliable biomarkers. The development of robust biomarkers remains paramount. CSF-derived and positron-emission-tomography (PET)-based biomarkers of neuroinflammation provide valuable insight into intracerebral inflammatory processes, assisting in early diagnosis, longitudinal monitoring of disease progression, and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. Combination therapy represents another promising strategy. Co-administration of anti-inflammatory agents with anti-amyloid therapies or cognitive-enhancing drugs may yield synergistic benefits by simultaneously targeting multiple pathological substrates of AD. Such a multifaceted approach has the potential to slow disease progression and improve cognitive function more effectively than monotherapy.

Evidence Strength, Bias, and Limitations

Across therapeutic classes, the overall strength of evidence remains moderate to low, reflecting the predominance of early-phase or preclinical studies. NSAIDs and omega-3 fatty acids are the most clinically advanced candidates; however, large prevention and symptomatic trials have produced inconsistent cognitive outcomes, providing at most moderate evidence. Natural compounds such as curcumin and resveratrol yield biochemical and biomarker improvements but lack adequately powered RCTs, resulting in low-quality evidence because of small sample sizes, surrogate end points, and formulation heterogeneity. Microglia-targeted agents (CSF1R, TREM2, NLRP3 and TLR modulators) and JAK/STAT inhibitors demonstrate strong mechanistic plausibility in animal models; however, they are supported only by preclinical or biomarker-level findings, classifying them as low-level evidence for clinical efficacy. Gene- and RNA-based strategies, as well as stem-cell therapies, remain exploratory; they are constrained by safety uncertainties, delivery challenges and insufficient long-term follow-up.

Substantial heterogeneity in study design, disease stage and outcome measures impedes cross-study comparison. Most human studies enrol small, heterogeneous cohorts, frequently at late symptomatic stages when neuroinflammatory cascades are entrenched and less amenable to reversal. Publication bias towards positive or mechanistically interesting results further distorts perceived efficacy, whereas negative or null findings remain under-reported. Translational gaps between animal and human studies persist, driven by inter-species differences in immune architecture, dosing regimens and treatment duration. Collectively, these factors limit generalisability and underscore the need for standardised outcome frameworks, longitudinal biomarker integration and adequately powered multicentre trials. Future emphasis on early-stage, precision-stratified interventions and transparent data reporting will be essential for strengthening the evidentiary base for neuroinflammation-targeted therapies in Alzheimer disease.

Conclusion

Despite substantial progress in elucidating the role of neuroinflammation in AD, several critical gaps remain, impeding clinical translation. Future investigations should prioritize validating positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of microglial activation, including TSPO, TREM2, and NLRP3 signatures, to facilitate early patient stratification and precisely monitor therapeutic responses in anti-inflammatory trials. Determining the optimal therapeutic window is also essential; comparative studies that initiate NLRP3- or JAK/STAT-pathway inhibition at early versus late disease stages may clarify the temporal dynamics of treatment efficacy. In addition, combination-therapy paradigms integrating anti-inflammatory agents with anti-amyloid or synapse-targeted interventions should undergo rigorous evaluation in adaptive or factorial randomized controlled trials to uncover potential synergistic effects. Advances in translational modeling, particularly the development of humanized or multi-omics animal models that recapitulate amyloid, tau, and inflammatory interactions, will be indispensable for improving predictive reliability. Finally, optimization of CNS delivery platforms—such as nanoparticle-based carriers or receptor-mediated transport systems—is required to augment the central bioavailability of anti-inflammatory small molecules and biologics. Addressing these gaps through coordinated, hypothesis-driven research will establish a robust translational framework for the development of safe, effective, and mechanistically grounded neuroinflammation-targeted therapies in AD.

Abbreviations

ADI: Alzheimer's Disease International; AD: Alzheimer's disease; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; ASOs: Antisense oligonucleotides; ATPase: Adenosine Tri-Phosphatase; Aβ: Amyloid-β; BBB: Blood-brain barrier; CDR-SB: Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; CNS: Central nervous system; COX: Cyclo-oxygenase; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; CSF1R: Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor; DAMPs: Damage-associated molecular patterns; DAP12: DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa; DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IFN-I: Type I interferon; IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, IL-10: Interleukin cytokines; ITAMs: Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs; JAK/STAT: Janus Kinase/Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MAPKs: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases; mAbs: Monoclonal antibodies; MSCs: Mesenchymal Stem Cells; NF-κB: Nuclear Factor-kappa B; NLRP3: NOD-like receptor protein 3; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; NSCs: Neural Stem Cells; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; RCTs: Randomised controlled trials; RNAi: RNA interference; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SIRT1: Sirtuin 1; SYK: Spleen tyrosine kinase; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TNF-α: Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha; TREM2: Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; WHO: World Health Organization

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

IL plan the conceptualization of articles, make investigations, writing-original drafts and review the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2024/SKK10/USM/02/8).

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent to publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data. Examples include ChatGPT, NovelAI, Jasper AI, Rytr AI, DALL-E, etc) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process before submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.